(Press-News.org) MADISON –– Scientists have been measuring global methane emissions for decades, but the boreal arctic —with a wide range of biomes including wetlands that extend across the northern parts of North America, Europe and Asia — is a key region where accurately estimating highly potent greenhouse gas emissions has been challenging.

Wetlands are great at storing carbon, but as global temperatures increase, they are warming up. That causes the carbon they store to be released into the atmosphere in the form of methane, which contributes to more global warming.

Now, researchers — including the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s Min Chen and Fa Li — have developed a new model that combines several data sources and uses physics-guided machine learning to more accurately understand methane emissions in the region. The improved model shows these wetlands are producing more methane over time.

“Wetland methane emissions are among the largest uncertainty in emissions from natural systems,” explains Chen, a professor of forest and wildlife ecology in the UW–Madison College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. “There are bacteria that live in the soils under the water of wetlands. That’s the perfect limited oxygen environment that is suitable for methane production.”

The researchers recently published their findings in the journal Nature Climate Change.

What problem are researchers trying to solve?

Currently, models used to quantify methane emissions in the boreal arctic wetlands don’t agree on how much of the gas is being emitted and whether the amount is increasing over time.

Previously, to help moderate emissions of carbon and methane, a collaboration of scientists created the Global Methane Budget under the Global Carbon Project, which they hope will inform policymakers.

However, Chen says, if scientists want to quantify the global methane budget accurately, they need to have more certainty in how much methane is emitted by these wetlands.

So, he and other researchers collaborated to build a more accurate and reliable model to better understand the region’s methane contribution as global temperatures rise.

Why do scientists need more information on emissions from these wetlands?

The boreal arctic holds up to 50% of the world’s wetlands.

With rising global temperatures, the region spends less time frozen over and plants and microbes are growing and productive for longer periods of time. This creates conditions for more methane emissions.

How does the new model help?

The team created the largest dataset yet for the region, which allowed them to develop a more accurate data-driven model of the boreal arctic wetlands’ methane emissions.

Chen says that previous models did not account for the full complexity of the physical and chemical processes at play, such as substrate availability, microbial activity, and other environmental conditions that influence methane emissions.

This is because they relied on partial emissions data collected from either a network of towers around the region or from chambers that take readings from the ground and surface of the water.

Though the towers are a “gold standard for measuring the flux of greenhouse gasses between land and the atmosphere,” Chen says, in the boreal arctic, they’re mostly not located close to the largest methane emitters in the region. Meanwhile, the chambers are near these hotspots.

Whereas prior models then only had one part of the complete picture and had to extrapolate to estimate the full picture, the new model combines data from both the tower and chamber sources.

The scientists also used artificial intelligence to create additional constraints that better account for how environmental variables like precipitation influence methane emissions.

What the new model is uncovering

Researchers are finding that methane emissions in the region have increased over time.

They’ve also found that higher temperatures and increased plant productivity are the biggest drivers of increased methane emissions in the region. When plants are more productive, they increase the amount of carbon in the soil, which acts as fuel for the soil-microbes that produce methane.

By improving scientific understanding and the ability to project greenhouse gas emissions, researcher can more accurately estimate temperature increases in the future, Chen says.

The team hopes to apply their model on a global scale, a task which will require wrangling a much larger data set.

This research was supported by a NASA Carbon Monitoring System grant (NNH20ZDA001N) and the Reducing Uncertainties in Biogeochemical Interactions through Synthesis and Computation (RUBISCO) Scientific Focus Area Project; the latter is sponsored by the Earth and Environmental Systems Modeling (EESM) Program under the Office of Biological and Environmental Research of the US Department of Energy Office of Science. This work was done in collaboration with researchers from Lawrence Berkely National Laboratory, University of Illinois Chicago, Stanford University, and the University of British Columbia.

END

New research finds boreal arctic wetlands are producing more methane over time

2024-03-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

TLI Investigator Dr. Wei Yan named Editor-in-Chief of the Andrology Journal

2024-03-18

The Lundquist Institute is proud to announce that Wei Yan, MD, PhD, a distinguished professor at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and Lundquist investigator, has been appointed by the American Society of Andrology and the European Academy of Andrology as the new Editor-in-Chief of Andrology, the highly-respected journal in the field of reproductive medicine.

Dr. Yan's appointment to Andrology is a testament to his dedication to reproductive medicine. With extensive editorial experience, including his previous roles as ...

New study reveals insights into COVID-19 antibody response durability

2024-03-18

Researchers at the Institute of Human Virology (IHV) at the University of Maryland School of Medicine published a new study in the Journal of Infectious Diseases investigating the antibody response following SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Long-lived plasma cells are responsible for durable antibody responses that persist for decades after immunization or infection. For example, infection with measles, mumps, rubella, or immunization with vaccines against tetanus or diphtheria elicit antibody responses that can last for many decades. By contrast, other infections and vaccines elicit short-lived antibody responses that last only a few ...

Climate change alters the hidden microbial food web in peatlands

2024-03-18

DURHAM, N.C. -- The humble peat bog conjures images of a brown, soggy expanse. But it turns out to have a superpower in the fight against climate change.

For thousands of years, the world’s peatlands have absorbed and stored vast amounts of carbon dioxide, keeping this greenhouse gas in the ground and not in the air. Although peatlands occupy just 3% of the land on the planet, they play an outsized role in carbon storage -- holding twice as much as all the world’s forests do.

The fate of all that carbon is uncertain in the face of climate change. And ...

Text nudges can increase uptake of COVID-19 boosters– if they play up a sense of ownership of the vaccine

2024-03-18

New research published in Nature Human Behavior suggests that text nudges encouraging people to get the COVID-19 vaccine, which had proven effective in prior real-world field tests, are also effective at prompting people to get a booster.

The key in both cases is to include in the text a sense of ownership in the dose awaiting them.

The paper, led by Hengchen Dai, an associate professor of management and organizations and behavioral decision making at the UCLA Anderson School of Management, and Silvia Saccardo, an associate professor of social and decision sciences at Carnegie Mellon University, draws on previous research published in Nature that examined the effectiveness ...

A new study shows how neurochemicals affect fMRI readings

2024-03-18

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – The brain is an incredibly complex and active organ that uses electricity and chemicals to transmit and receive signals between its sub-regions.

Researchers have explored various technologies to directly or indirectly measure these signals to learn more about the brain. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), for example, allows them to detect brain activity via changes related to blood flow.

Yen-Yu Ian Shih, PhD, professor of neurology and associate director of UNC’s Biomedical Research Imaging Center, and his fellow lab members have long been curious about how neurochemicals in the brain regulate and influence neural activity, ...

Digital reminders for flu vaccination improves turnout, but not clinical outcomes in older adults

2024-03-18

Embargoed for release until 5:00 p.m. ET on Monday 18 March 2024

Annals of Internal Medicine Tip Sheet

@Annalsofim

Below please find summaries of new articles that will be published in the next issue of Annals of Internal Medicine. The summaries are not intended to substitute for the full articles as a source of information. This information is under strict embargo and by taking it into possession, media representatives are committing to the terms of the embargo not only on their own behalf, but also on behalf of the organization they represent.

----------------------------

1. Digital reminders for flu vaccination improves ...

Avatar will not lie... or will it? Scientists investigate how often we change our minds in virtual environments

2024-03-18

How confident are you in your judgments and how well can you defend your opinions? Chances are that they will change under the influence of a group of avatars in a virtual environment. Scientists from SWPS University investigated the human tendency to be influenced by the opinions of others, including virtual characters.

We usually conform to the views of others for two reasons. First, we succumb to group pressure and want to gain social acceptance. Second, we lack sufficient knowledge and perceive the group as a source of a better interpretation of the current situation, describes Dr. Konrad Bocian from the Institute of Psychology at SWPS University.

So far, only a few studies ...

8-hour time-restricted eating linked to a 91% higher risk of cardiovascular death

2024-03-18

Research Highlights:

A study of over 20,000 adults found that those who followed an 8-hour time-restricted eating schedule, a type of intermittent fasting, had a 91% higher risk of death from cardiovascular disease.

People with heart disease or cancer also had an increased risk of cardiovascular death.

Compared with a standard schedule of eating across 12-16 hours per day, limiting food intake to less than 8 hours per day was not associated with living longer.

Embargoed until 3 p.m. CT/4 p.m. ET, Monday, March 18, 2024

CHICAGO, March 18, 2024 — An analysis ...

Alternative tidal wetlands in plain sight overlooked Blue Carbon superstars

2024-03-18

Blue Carbon projects are expanding globally; however, demand for credits outweighs the available credits for purchase.

Currently, only three types of wetlands are considered Blue Carbon ecosystems: mangroves, saltmarsh and seagrass.

However, other tidal wetlands also comply with the characteristics of what is considered Blue Carbon, such as tidal freshwater wetlands, transitional forests and brackish marshes.

In a new study, scientists from Australia, Indonesia, Singapore, South Africa, Vietnam, the US and Mexico have highlighted the increasing opportunities for Blue Carbon projects for the conservation, restoration and improved management of highly threatened ...

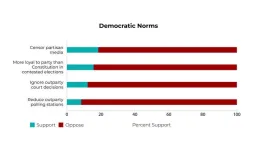

The majority of Americans do not support anti-democratic behavior, even when elected officials do

2024-03-18

EMBARGOED UNTIL MARCH 18 AT 3 P.M. EST

Recently, fundamental tenets of democracy have come under threat, from attempts to overturn the 2020 election to mass closures of polling places.

A new study from the Polarization Research Lab, a collaboration among researchers at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania, Dartmouth College, and Stanford University, has found that despite this surge in anti-democratic behavior by U.S. politicians, the majority of Americans oppose anti-democratic attitudes and reject partisan violence.

From September 2022 to October 2023, a period which included the 2022 midterm ...