In the elderly, these newly imported pathogens can gain the upper hand frighteningly quickly. Unfortunately, however, vaccination in this age group isn’t as effective as it is in younger people.

Now a study conducted in mice by Stanford Medicine and the National Institute of Health’s Rocky Mountain Laboratories provides tantalizing evidence that it may one day be possible to rev up an elderly immune system with a one-time treatment that modulates the composition of a type of immune cell.

The treatment significantly improved the ability of geriatric animals’ immune systems to tackle a new virus head on, as well as to respond vigorously to vaccination — enabling them to fight off a new threat months later.

“This is a real paradigm shift — researchers and clinicians should think in a new way about the immune system and aging,” said postdoctoral scholar Jason Ross, MD, PhD. “The idea that it’s possible to tune the entire immune system of millions of cells simply by affecting the function of such a rare population is surprising and exciting.”

Ross and Lara Myers, PhD, a research fellow at Rocky Mountain Laboratories, are the lead authors of the study, which will be published March 27 in Nature. Irving Weissman, MD, professor of pathology and of developmental biology, and Kim Hasenkrug, PhD, the chief of Rocky Mountain Laboratories’ Retroviral Immunology Section, are the senior authors of the research.

A shift in the immune system

The targeted cells are a subset of what’s known as hematopoietic stem cells, or HSCs. HSCs are the granddaddies of the immune system, giving rise to all the other types of blood and immune cells including B and T cells, which are collectively known as lymphocytes. As we age, our HSCs begin to favor the production of other immune cells called myeloid cells over lymphocytes. This shift hampers our ability to fully react to new viral or bacterial threats and makes our response to vaccination much less robust than that of younger people.

“Older people just don’t make many new B and T cell lymphocytes,” said Weissman, who is the Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Professor in Clinical Investigation in Cancer Research. “During the start of the COVID-19 pandemic it quickly became clear that older people were dying in larger numbers than younger people. This trend continued even after vaccinations became available. If we can revitalize the aging human immune system like we did in mice, it could be lifesaving when the next global pathogen arises.”

Weissman was the first to isolate HSCs in mice and humans in the late 1980s. In the years since, he and his colleagues have investigated the molecular minutiae of these cells, painstakingly tracing the complicated relationships among the scores of cell types that arise in their wake.

Some of these descendants make up what’s known as the adaptive immune system: highly specialized B and T lymphocytes that each recognize just one particular three-dimensional structure — perhaps a pointy bit here or a telltale knobby clump there — that betrays an invading virus or bacteria. Like trained assassins once they spot their mark, B lymphocytes churn out antibodies that latch onto the telltale structures and target infected or foreign cells for destruction, while various subtypes of T lymphocytes either demolish infected cells or raise a hue and cry to summon other immune cells to finish off the enemy.

The specificity of the B and T lymphocytes allows the immune system to have memory; once you’ve been exposed to a specific invader, the body reacts swiftly and decisively if that same pathogen is seen again. This is the basic concept behind vaccination — trigger an initial response to a harmless mimic of a dangerous bacteria or virus. In response, the lymphocytes that recognize the invader not only give rise to cells that eliminate the infection but also generate long-lived memory B and T cells that, in some cases, can last a lifetime. Thus, the system is primed when the threat becomes real.

Another key part of our immune system is called innate immunity, and it’s much less discriminating. In the blood, it’s run by a class of cells called myeloid cells. Like school janitors, these cells scour the body, gobbling up any unfamiliar cells or bits of detritus. They also trigger inflammatory responses, which recruit other cells and chemicals to infected sites. Inflammation helps the body protect itself against invaders, but it can be a major problem when triggered inappropriately or overenthusiastically, and aging has been linked to chronic inflammation in humans.

An evolutionary disadvantage

Ross and Weissman knew from previous research that during aging, the number of HSCs that make balanced proportions of lymphocytes and myeloid cells decline, while those that are myeloid-biased increase their numbers. This favors the production of myeloid cells. Early in human history, when people rarely left their birthplace and lived shorter lives, this gradual change probably had no consequences (it may even have been favorable) because people were likely to encounter all their surrounding pathogens by young adulthood and be protected by their memory lymphocytes. But now it’s distinctly disadvantageous.

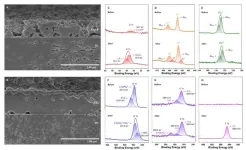

The researchers wondered if they could tilt the balance back toward a younger immune system by depleting myeloid-leaning HSCs and allowing the more balanced HSCs to replace them. Their hunch was correct. Mice between 18 and 24 months old (doddering in the mouse world) that were treated with an antibody targeting the myeloid-leaning HSCs for destruction had more of the balanced HSCs — and more new, naïve B and T lymphocytes — than their untreated peers even several weeks later.

“These new, naïve lymphocytes provide better immune coverage for novel infections like those humans increasingly encounter as our world becomes more global,” Weissman said. “Without this renewal, these new infectious agents would not be recognized by the existing pool of memory lymphocytes.”

The treatment also reduced some negative outcomes like inflammation that can arise when an elderly immune system grapples with a new pathogen.

“Not only did we see a shift toward cells involved in adaptive immunity, but we also observed a dampening in the levels of inflammatory proteins in the treated animals,” Ross said. “We were surprised that a single course of treatment had such a long-lasting effect. The difference between the treated and untreated animals remained dramatic even two months later.”

When the treated animals were vaccinated eight weeks later against a virus they hadn’t encountered before, their immune systems responded more vigorously than untreated animals’, and they were significantly better able to resist infection by that virus. (In contrast, young mice used as controls passed all the challenges with flying colors.)

“Every feature of an aging immune system — functional markers on the cells, the prevalence of inflammatory proteins, the response to vaccination and the ability to resist a lethal infection — was impacted by this single course of treatment targeting just one cell type,” Ross said.

Finally, the researchers showed that mouse and human myeloid-biased HSCs are similar enough that it may one day be possible to use a similar technique to revitalize aging human immune systems, perhaps making a person less vulnerable to novel infections and improving their response to vaccination.

“We believe that this study represents the first steps in applying this strategy in humans,” Ross said.

The study also has interesting implications for stem cell biology and the way HSCs rely on biological niches, or specific neighborhoods of cells, for their longevity and function throughout our lives.

“Most people in immunology have believed that you lose these kinds of tissue-specific stem cells as you grow older,” Weissman said. “But that is completely wrong. The problems arise when you start to favor one type of HSC over another. And we’ve shown in mice that this can be reversed. This finding changes how we think about stem cells during every stage of aging.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grants R35CA220434, R01DK115600 and R01AI143889), the Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Fund for Cancer Research, the RSNA Resident/Fellow Research Grant, a Stanford Cancer Institute Fellowship grant, and the Ellie Guardino Research Fund.

# # #

About Stanford Medicine

Stanford Medicine is an integrated academic health system comprising the Stanford School of Medicine and adult and pediatric health care delivery systems. Together, they harness the full potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education and clinical care for patients. For more information, please visit med.stanford.edu.

END