(Press-News.org) Electrons—these infinitesimally small particles that are known to zip around atoms—continue to amaze scientists despite the more than a century that scientists have studied them. Now, physicists at Princeton University have pushed the boundaries of our understanding of these minute particles by visualizing, for the first time, direct evidence for what is known as the Wigner crystal—a strange kind of matter that is made entirely of electrons.

The finding, published in the April 11th issue of the journal Nature, confirms a 90-year-old theory that electrons can assemble into a crystal-like formation of their own, without the need to coalesce around atoms. The research could help lead to the discovery of new quantum phases of matter when electrons behave collectively.

“The Wigner crystal is one of the most fascinating quantum phases of matter that has been predicted and the subject of numerous studies claiming to have found at best indirect evidence for its formation,” said Al Yazdani, the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor in Physics at Princeton University and the senior author of the study. “Visualizing this crystal allows us not only to watch its formation, confirming many of its properties, but we can also study it in ways you couldn’t in the past.”

In the 1930s, Eugene Wigner, a Princeton professor of physics and winner of the 1963 Nobel Prize for his work in quantum symmetry principles, wrote a paper in which he proposed the then-revolutionary idea that interaction among electrons could lead to their spontaneous arrangement into a crystal-like configuration, or lattice, of closely packed electrons. This could only occur, he theorized, because of their mutual repulsion and under conditions of low densities and extremely cold temperatures.

“When you think of a crystal, you typically think of an attraction between atoms as a stabilizing force, but this crystal forms purely because of the repulsion between electrons,” said Yazdani, who is the inaugural co-director of the Princeton Quantum Institute and director of the Princeton Center for Complex Materials.

For a long time, however, Wigner’s strange electron crystal remained in the realm of theory. It was not until a series of much later experiments that the concept of an electron crystal transformed from conjecture to reality. The first of these was conducted in the 1970s when scientists at Bell Laboratories in New Jersey created a “classical” electron crystal by spraying electrons on the surface of helium and found that they responded in a rigid manner like a crystal. However, the electrons in these experiments were very far apart and behaved more like individual particles than a cohesive structure. A true Wigner crystal, instead of following the familiar laws of physics in the everyday world, would follow the laws of quantum physics, in which the electrons would act not like individual particles but more like a single wave.

This led to a whole series of experiments over the next decades that proposed various ways to create quantum Wigner crystals. These experiments were greatly advanced in the 1980s and 1990s when physicists discovered how to confine electrons’ motion to atomically thin layers using semiconductors. The application of a magnetic field to such layered structures also makes electrons move in a circle, creating favorable conditions for crystallization. But these experiments were never able to directly observe the crystal. They were only able to suggest its existence or indirectly infer it from how electrons flow through the semiconductor.

“There are literally hundreds of scientific papers that study these effects and claim that the results must be due to the Wigner crystal,” Yazdani said, “but one can’t be sure, because none of these experiments actually see the crystal.”

An equally important consideration, Yazdani noted, is that what some researchers think is evidence of a Wigner crystal could be the result of imperfections or other periodic structures inherent to the materials used in the experiments. “If there are any imperfections, or some form of periodic substructure in the material, it is possible to trap electrons and find experimental signatures that are not due to the formation of a self-organized ordered Wigner crystal itself, but due to electrons ‘stuck’ near an imperfection or trapped because of the material’s structure,” he said.

With these considerations in mind, Yazdani and his research team set about to see whether they could directly image the Wigner crystal using a scanning tunneling microscope (STM), a device that relies on a technique called “quantum tunneling” rather than light to view the atomic and subatomic world. They also decided to use graphene, an amazing material that was discovered in the 21st century and has been used in many experiments involving novel quantum phenomena. To successfully conduct the experiment, however, the researchers had to make the graphene as pristine and as devoid of imperfections as possible. This was key to eliminating the possibility of any electron crystals forming because of material imperfections.

The results were impressive. “Our group has been able to make unprecedentedly clean samples that made this work possible,” Yazdani said. “With our microscope we can confirm that the samples are without any atomic imperfection in the graphene atomic lattice or foreign atoms on its surface over regions with hundreds of thousands of atoms.”

To make the pure graphene, the researchers exfoliated two carbon sheets of graphene in a configuration that is called Bernal-stacked bilayer graphene (BLG). They then cooled the sample down to extremely low temperatures—just a fraction of a degree above absolute zero—and applied a magnetic field perpendicular to the sample, which created a two-dimensional electron gas system within the thin layers of graphene. With this, they could tune the density of the electrons between the two layers.

“In our experiment, we can image the system as we tune the number of the electrons per unit area,” said Yen-Chen Tsui, a graduate student in physics and the first author of the paper. “Just by changing the density, you can initiate this phase transition and find electrons spontaneously form into an ordered crystal.”

This happens, Tsui explained, because at low densities, the electrons are far apart from each other—and they’re situated in a disordered, disorganized fashion. However, as you increase the density, which brings the electrons closer together, their natural repulsive tendencies kick in and they start to form an organized lattice. Then, as you increase the density further, the crystalline phase will melt into an electron liquid.

Minhao He, a postdoctoral researcher and co-first author of the paper, explained this process in greater detail. “There is an inherent repulsion between the electrons,” he said. “They want to push each other away, but in the meantime the electrons cannot be infinitely apart due to the finite density. The result is that they form a closely packed, regularized lattice structure, with each of the localized electron occupying a certain amount of space.”

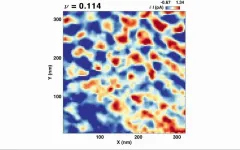

When this transition formed, the researchers were able to visualize it using the STM. “Our work provides the first direct images of this crystal. We proved the crystal is really there and we can see it,” said Tsui.

However, just visualizing the crystal wasn’t the end of the experiment. A concrete image of the crystal allowed them to distinguish some of the crystal’s characteristics. They discovered that the crystal is triangular in configuration, and that it can be continuously tuned with the density of the particles. This led to the realization that the Wigner crystal is actually quite stable over a very long range, a conclusion that is contrary to what many scientists have surmised.

“By being able to continuously tune its lattice constant, the experiment proved that the crystal structure is the result of the pure repulsion between the electrons,” said Yazdani.

The researchers also discovered several other interesting phenomena that will no doubt warrant further investigation in the future. They found that the location to which each electron is localized in the lattice appears in the images with a certain amount of “blurring,” as if the location is not defined by a point but a range position in which the electrons are confined in the lattice. The paper described this as the “zero-point” motion of electrons, a phenomenon related to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. The extent of this blurriness reflects the quantum nature of the Wigner crystal.

”Electrons, even when frozen into a Wigner crystal, should exhibit strong zero-point motion,” said Yazdani. “It turns out this quantum motion covers a third of the distance between them, making the Wigner crystal a novel quantum crystal.”

Yazdani and his team are also examining how the Wigner crystal melts and transitions into other exotic liquid phases of interacting electrons in a magnetic field. The researchers hope to image these phases just as they have imaged the Wigner crystal.

“Direct observation of a magnetic field-induced Wigner crystal,” by Yen-Chen Tsui, Minhao He, Yuwen Hu, Ethan Lake, Taige Wang, Kenji Watanabe, Takashi Taniguchi, Michael P. Zaletel, and Ali Yazdani was published April 11, 2024 in the journal Nature DOI to come.

Graduate student Yen-Chen Tsui, postdoctoral research associate Minhao He, and Yuwen Hu, who obtained her Ph.D. from the Princeton Department of Physics in 2023 and is now a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford, all contributed equal to this work. Other collaborators include, at the University of California-Berkeley, theoretical physicists Ethan Lake, Taige Wang, and Professor Michael Zaletel (also a member of the Material Science Division at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory), and Kenji Watanabe and Takashi Taniguchi from National Institute for Materials Science and International Center for Materials Nanoarchitectonics, respectively.

The work at Princeton was primarily supported by DOE-BES grant DE-FG02-07ER46419 and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation’s EPiQS initiative grants GBMF9469. Other support for the experimental infrastructure at Princeton was provided by NSF-MRSEC through the Princeton Center for Complex Materials NSF6 DMR- 2011750, ARO MURI (W911NF-21-2-0147), and ONR N00012-21-1-2592.

The team also acknowledges the hospitality of the Aspen Center for Physics, which is supported by National Science Foundation grant PHY-1607611, where part of this work was carried out. Work at UC Berkeley was supported by U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division, under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, within the van der Waals Heterostructures Program (KCWF16).

END

Quantum crystal of frozen electrons—the Wigner crystal—is visualized for the first time

Princeton University researchers detect a strange form of matter that has eluded direct detection for some 90 years

2024-04-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A new coating method in mRNA engineering points the way to advanced therapies

2024-04-10

Researchers from Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU) have developed a novel method for chemically modifying engineered messenger RNA molecules, allowing greater control of their biological functions and advancing mRNA therapeutic technologies

Tokyo, Japan – Medicine can help to treat certain illnesses, e.g., antibiotics can help overcome infections, but a new, promising field of medicine involves providing our body with the “blueprint” for how to defeat illnesses on its own.

mRNA therapeutics ...

Stanford Medicine study flags unexpected cells in lung as suspected source of severe COVID

2024-04-10

The lung-cell type that’s most susceptible to infection by SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is not the one previously assumed to be most vulnerable. What’s more, the virus enters this susceptible cell via an unexpected route. The medical consequences may be significant.

Stanford Medicine investigators have implicated a type of immune cell known as an interstitial macrophage in the critical transition from a merely bothersome COVID-19 case to a potentially deadly one. Interstitial macrophages are situated deep in the lungs, ...

Studies uncovered why urine sprayed by cats emits a pungent odor

2024-04-10

Cats communicate with others through their scents. One of their scent marking behaviors is spraying urine on vertical surfaces such as walls and furniture. Although spraying plays an essential role in the feline world, it often poses challenges for pet owners because of its strong and pungent odor. Consequently, the website is overflowing with posts discussing the issue of cat spraying. Notably, sprayed urine has a more pungent odor on the human nose than normal urine in their litter boxes. While it is believed that sprayed urine contains additional chemicals possibly ...

Survivors of severe COVID face persistent health problems

2024-04-10

UC San Francisco researchers examined COVID-19 patients across the United States who survived some of the longest and most harrowing battles with the virus and found that about two-thirds still had physical, psychiatric, and cognitive problems for up to a year later.

The study, which appears April 10, 2024, in the journal Critical Care Medicine, reveals the life-altering impact of SARS-CoV-2 on these individuals, the majority of whom had to be placed on mechanical ventilators for an average of one month.

Too sick to be discharged to a skilled nursing ...

New report ‘braids’ Indigenous and Western knowledge for forest adaptation strategies against climate change

2024-04-10

Link to release:

https://www.washington.edu/news/2024/04/10/forest-report/

Link to related coverage:

https://today.oregonstate.edu/news/indigenous-knowledge-western-science-braided-recommendations-land-managers

FROM: James Urton

University of Washington

206-543-2580

jurton@uw.edu

(Note: researcher contact information at end)

For Immediate Release

April 10, 2024

There are 154 national forests in the United States, covering nearly 300,000 square miles of forests, woodlands, shrublands, wetlands, meadows ...

Improving dementia care in nursing homes: Learning from the pandemic years

2024-04-10

INDIANAPOLIS – No one associated with nursing homes – as residents or their families, friends, staff or administrators – is unaware of the massive impact of the pandemic on these facilities which provide essential services to a growing number of older adults, many living with cognitive impairment.

In “Learning from the experience of dementia care for nursing home residents during the pandemic,” an editorial published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, Regenstrief Institute and Indiana University School of ...

Respiratory allergies: newly discovered molecule plays a major role in triggering inflammation

2024-04-10

The inflammation process plays a crucial role in allergic respiratory diseases, such as asthma and allergic rhinitis. Although the pulmonary epithelium, the carpet of cells that forms the inner surface of the lungs, is recognised as a major player in the respiratory inflammation that causes these diseases, the underlying mechanisms are still poorly understood.

A research team has identified one of the molecules responsible for triggering these allergic reactions, in a study co-led by two CNRS and Inserm scientists working at l’Institut de pharmacologie et de biologie structural (CNRS/Université Toulouse ...

A BiCIKL ride to the Empowering Biodiversity Research conference for a report on a 3-year endeavor towards FAIR biodiversity data

2024-04-10

Leiden - also known as the ‘City of Keys’ and the 'City of Discoveries' - was aptly chosen to host the third Empowering Biodiversity Research (EBR III) conference. The two-day conference - this time focusing on the utilisation of biodiversity data as a vehicle for biodiversity research to reach to Policy - was held in a no less fitting locality: the Naturalis Biodiversity Center.

On 25th and 26th March 2024, the delegates got the chance to learn more about the latest discoveries, trends and innovations from scientists, as well as various stakeholders, including representatives of policy-making bodies, research institutions and infrastructures. ...

Visiting white parts of town make some Black kids feel less safe

2024-04-10

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Some Black youth feel less safe when they visit predominantly white areas of their city, a new study in Columbus has found.

And it was those Black kids who spent the most time in white-dominated areas who felt less safe, said Christopher Browning, lead author of the study and professor of sociology at The Ohio State University.

“Familiarity with white neighborhoods doesn’t make Black kids feel more comfortable and safer. In fact, familiarity seems to reveal ...

Deforestation harms biodiversity of the Amazon’s perfume-loving orchid bees

2024-04-10

LAWRENCE — A survey of orchid bees in the Brazilian Amazon state of Rondônia, carried out in the 1990s, is shedding new light the impact of deforestation on the scent-collecting pollinators, which some view as bellwethers of biodiversity in the neotropics.

The findings, from a researcher at the University of Kansas, are published today in the peer-reviewed journal Biological Conservation.

“This study on orchid bees was an add-on to previous research on stingless bees. Orchid bees are so easy to collect, so we added them to ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

Greaux Healthy Day declared in Lake Charles: Pennington Biomedical’s Greaux Healthy Initiative highlights childhood obesity challenge in SWLA

Into the heart of a dynamical neutron star

The weight of stress: Helping parents may protect children from obesity

Cost of physical therapy varies widely from state-to-state

Material previously thought to be quantum is actually new, nonquantum state of matter

Employment of people with disabilities declines in february

Peter WT Pisters, MD, honored with Charles M. Balch, MD, Distinguished Service Award from Society of Surgical Oncology

Rare pancreatic tumor case suggests distinctive calcification patterns in solid pseudopapillary neoplasms

Tubulin prevents toxic protein clumps in the brain, fighting back neurodegeneration

Less trippy, more therapeutic ‘magic mushrooms’

Concrete as a carbon sink

[Press-News.org] Quantum crystal of frozen electrons—the Wigner crystal—is visualized for the first timePrinceton University researchers detect a strange form of matter that has eluded direct detection for some 90 years