(Press-News.org) Monday, April 15, 2024 - Toronto - From a young age, people learn the importance of paying attention to the environment around them. Less emphasized is the value of paying attention to their inner environment. Neuroscientists are increasingly studying how looking inward via mindfulness training can affect everything from depression and memory to stress levels and aging. As researchers work to uncover the neural mechanisms underlying these brain changes, they hope to elucidate best practices for people who want to incorporate mindfulness in their lives.

“Attentional training is a mechanism by which you can train your brain,” says Erika Nyhus of Bowdoin College, who is chairing a session with new research on mindfulness at the annual meeting of the Cognitive Neuroscience Society (CNS) in Toronto. “Work to understand the neural mechanisms at play in this mindfulness training show potential pathways toward enhanced cognition but there are no short-cuts. It takes practice.”

The cognitive neuroscientists presenting their latest findings at CNS 2024 are excited about the potential benefits of mindfulness training not only to individuals but also to researchers exploring the roots of cognition in the brain. Together, their research suggests that individual differences in sensory and cognitive processing in our brains can both predict mental health and be amenable to training through new technological applications.

Tapping into inward senses

Tuning into interoception, how someone senses their body’s internal state, is an important component of mindfulness training that could aid in managing mood disorders such as depression. “Interoception matters in depression because our emotions are made up of both visceral body sensations and our cognitive appraisals of these sensations that help us make sense of those feelings and put them into context,” says Norman Farb of the University of Toronto Mississauga. “For example, a fluttering in our belly could be judged as excitement or anxiety depending on our context and appraisal habits.”

Farb and his colleagues are working to disentangle how the brain processes these interoceptive signals. They are finding that training that focuses on internally paying attention is sufficient to pull resources away from “deeply entrenched appraisal habits, empowering the integration of novel sensation and feelings, which can help a person become 'unstuck' in how they relate to themselves and the world around them,” he says.

In a recent large neuroimaging study of vulnerability to depression relapse, published in NeuroImage Clinical, Farb and colleagues found that one of the biggest indicators of past, present, and future depression was how much individuals inhibited sensory and motor processing. Those who maintained rather than inhibited this processing relapsed into depression at much lower rates, despite having a history of depression that indicated a high relapse risk. “This result contrasts other neural indicators of depression as being driven by too much activity in regions supporting judgment and appraisal,” Farb says, “And it points to the importance of maintaining sensation in times of stress as a sign of mental resilience.”

In another set of studies published in ENeuro, Farb and colleagues looked specifically at attention to the breath, a central practice in mindfulness training. They found that while attention to external senses such as vision activates the corresponding visual cortex, attention to the breath tends to deactivate the cerebral cortex, including regions where appraisal and cognitive control occurs. “This suggests that mindfulness exercises may first help people to use their attention to stop doing so much with their brains, providing relief from rumination and judgment,” Farb says. “It also has a fascinating implication for how interoception differs from the external senses: interoceptive processing may be continuously represented in the brain to regulate biological processes such as the breath or heartbeat. To detect it, we just need to quiet down.”

As Farb’s team’s research continues to understand how paying attention to the breath changes brain processes, they are also excited to begin applying what they have learned in technology-driven applications. They hope to create “microinterventions,” such as daily self reflections that will enable individuals to tune into interoception to help manage emotions. “There's a lot more work to be done to make mindfulness communicable, relevant, and useful to the current generation of humans on the planet,” he says.

Harnessing the power of technology

For the past decade, David Ziegler has been working on a digital meditation-inspired game rooted in the fundamental concept of internal attention. His team at Neuroscape at the University of California, San Francisco, has completed clinical trials and testing of the game with several groups in an effort to bring the practice of meditation to anyone, anywhere. “Even though not everyone will resonate with the practice, they should at least have the opportunity to engage with it in an effective way and judge for themselves if they think they would benefit from it,” he says.

Their mediation app, MediTrain, is rooted in basic research in neuroplasticity and specifically how the brain can compensate for deficits in attentional control. At CNS 2024, Ziegler is presenting data from recently published papers that used the app in young adults, aging adults, and adolescents with childhood neglect, as well as a new study in healthy older adults. In all the work, the researchers found attention benefits from the digital training, and in the newest study they found that the training also led to a decrease in stress reactivity and a lengthening of telomeres (a blood biomarker of cellular aging).

The app uses an adaptive algorithm that makes the sessions more difficult if an individual is doing well or easier if they are struggling. “It’s a personalized experience for every individual at every point in their training,” Ziegler explains.

In one of the recently published studies in Nature Human Behaviour, the researchers recruited healthy young adults to participate in 6 weeks of meditation training via the app. The found gains in both sustained attention and working memory in this group, which has proven difficult for researchers in the past. These improvements were associated with positive changes in key neural signatures of attentional control. Thus by focusing their attention inward, young adults were able to improve their outward attention.

The biggest challenges in this work, Ziegler says, is determining who responds to meditation and how much of a “dose” someone needs to reap the benefit. “I truly believe that technology is key to answering those questions,” he says. “One of our biggest upcoming studies is a nationwide dose-response study of MediTrain in thousands of older adults across the country that can really only be done with a fully mobile, digital form of meditation.”

The researchers participating in the CNS 2024 symposium on mindfulness and meditation are eager to see the potential benefits of these practices extend to broad populations. Nyhus, Farb, and Ziegler not only all study mindfulness and meditation but they are also practitioners, though they may have started with some hesitance or skepticism.

“As a scientist, I am always skeptical, wondering is it really worth all this hype?” says Nyhus, whose work in this space was inspired by an 8-week course she took in Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction. She will be presenting results from a study that used principles from that course to study changes in episodic memory. “You see mindfulness training everywhere and don’t know if there is anything to it, but I was shocked to see the results we got in the lab.” Nyhus hopes that by discovering the underlying mechanisms behind these results, she and others can leverage mindfulness training as a tool for cognitive enhancement.

–

The symposium “Neurocognitive Mechanisms of Mindfulness: Insights from Basic Research and Translational Science” is taking place at 10amET on Monday, April 15, as part of the CNS 2024 annual meeting from April 13-16, 2024 in Toronto, Canada.

CNS is committed to the development of mind and brain research aimed at investigating the psychological, computational, and neuroscientific bases of cognition. Since its founding in 1994, the Society has been dedicated to bringing its 2,000 members worldwide the latest research to facilitate public, professional, and scientific discourse.

END

Mindfulness and meditation: inward attention as a tool for mental health

CNS 2024

2024-04-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

No two worms are alike

2024-04-15

Sport junkie or couch potato? Always on time or often late? The animal kingdom, too, is home to a range of personalities, each with its own lifestyle. In a study just released in the journal PLOS Biology, a team led by Sören Häfker and Kristin Tessmar-Raible from the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) and the University of Vienna report on a surprising discovery: even simple marine polychaete worms shape their day-to-day lives on the basis of highly individual rhythms. This diversity ...

AGA announces new partnership with Target RWE to gather real world data on eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE)

2024-04-15

Bethesda, MD (April 15, 2024) - The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) and Target RWE have partnered to significantly expand real-world data available for serious, and often chronic, gastroenterological diseases. This partnership will also allow Target RWE to incorporate AGA’s eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) severity index tool, I-SEE, into the TARGET-GASTRO registry.

AGA led the international team of more than 30 multidisciplinary experts that developed the Index of Severity for EoE (I-SEE) in 2022. I-SEE is the first-ever severity index for eosinophilic esophagitis, which provides a simple system for physicians to assess and track ...

How trauma gets 'under the skin'

2024-04-15

A University of Michigan study has shown that traumatic experiences during childhood may get "under the skin" later in life, impairing the muscle function of people as they age.

The study examined the function of skeletal muscle of older adults paired with surveys of adverse events they had experienced in childhood. It found that people who experienced greater childhood adversity, reporting one or more adverse events, had poorer muscle metabolism later in life. The research, led by University of Michigan Institute for Social Research scientist Kate Duchowny, is published in Science Advances.

Duchowny and her co-authors used ...

Researchers resolve old mystery of how phages disarm pathogenic bacteria

2024-04-15

MEDIA INQUIRES

WRITTEN BY

Laura Muntean

Ashley Vargo

laura.muntean@ag.tamu.edu

ashley.vargo@ag.tamu.edu

601-248-1891

Depiction ...

Green-to-red transformation of Euglena gracilis using bonito stock and intense red light

2024-04-15

Over the past few years, people have generally become more conscious about the food they consume. Thanks to easier access to information as well as public health campaigns and media coverage, people are more aware of how nutrition ties in with both health benefits and chronic diseases. As a result, there is an ongoing cultural shift in most countries, with people prioritizing eating healthily. In turn, the demand for healthier food options and nutritional supplements is steadily growing.

In line with these changes, Assistant Professor Kyohei ...

New study sheds light on the mechanisms underlying the development of malignant pediatric brain tumors

2024-04-15

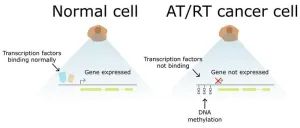

A new study conducted by researchers at Tampere University and Tampere University Hospital revealed how aberrant epigenetic regulation contributes to the development of atypical teratoid/rhabdoid (AT/RT) tumours, which are aggressive brain tumours that mainly affect young children. There is an urgent need for more research in this area as current treatment options are ineffective against these highly malignant tumours.

Most tumours take a long time to develop as harmful mutations gradually accumulate in cells’ DNA over time. AT/RT tumours are a rare exception, ...

Evolution's recipe book: How ‘copy paste’ errors cooked up the animal kingdom

2024-04-15

700 million years ago, a remarkable creature emerged for the first time. Though it may not have been much to look at by today’s standards, the animal had a front and a back, a top and a bottom. This was a groundbreaking adaptation at the time, and one which laid down the basic body plan which most complex animals, including humans, would eventually inherit.

The inconspicuous animal resided in the ancient seas of Earth, likely crawling along the seafloor. This was the last common ancestor of bilaterians, ...

Switch to green wastewater infrastructure could reduce emissions and provide huge savings according to new research

2024-04-15

Embargo: This journal article is under embargo until April 15 at 10 a.m. BST/London (5 a.m. EDT/3 a.m. MDT). Media may conduct interviews around the findings in advance of that date, but the information may not be published, broadcast, or posted online until after the release window. Journalists are permitted to show papers to independent specialists under embargo conditions, solely for the purpose of commenting on the work described

University researchers have shown that a transition to green wastewater-treatment approaches in the U.S. that leverages the potential of carbon-financing could save a staggering $15.6 billion and just under 30 million tonnes of CO2-equivalent emissions ...

Specific nasal cells protect against COVID-19 in children

2024-04-15

Important differences in how the nasal cells of young and elderly people respond to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, could explain why children typically experience milder COVID-19 symptoms, finds a new study led by researchers at UCL and the Wellcome Sanger Institute.

The study, published in Nature Microbiology, focused on the early effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the cells first targeted by the viruses, the human nasal epithelial cells (NECs).

These cells were donated from healthy participants from Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH), University College London Hospital (UCLH) and the Royal ...

Tropical forests can't recover naturally without fruit eating birds

2024-04-15

New research from the Crowther Lab at ETH Zurich illustrates a critical barrier to natural regeneration of tropical forests. Their models – from ground-based data gathered in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil - show that when wild tropical birds move freely across forest landscapes, they can increase the carbon storage of regenerating tropical forests by up to 38 percent.

Birds seed carbon potential

Fruit eating birds such as the Red-Legged Honeycreeper, Palm Tanager, or the Rufous-Bellied Thrush play a vital role in forest ecosystems by consuming, excreting, and ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

Anxiety, depression, and care barriers in adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities

[Press-News.org] Mindfulness and meditation: inward attention as a tool for mental healthCNS 2024