(Press-News.org) UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Ancient, expansive tracts of continental crust called cratons have helped keep Earth’s continents stable for billions of years, even as landmasses shift, mountains rise and oceans form. A new mechanism proposed by Penn State scientists may explain how the cratons formed some 3 billion years ago, an enduring question in the study of Earth’s history.

The scientists reported today (May 8) in the journal Nature that the continents may not have emerged from Earth’s oceans as stable landmasses, the hallmark of which is an upper crust enriched in granite. Rather, the exposure of fresh rock to wind and rain about 3 billion years ago triggered a series of geological processes that ultimately stabilized the crust — enabling the crust to survive for billions of years without being destroyed or reset.

The findings may represent a new understanding of how potentially habitable, Earth-like planets evolve, the scientists said.

“To make a planet like Earth you need to make continental crust, and you need to stabilize that crust,” said Jesse Reimink, assistant professor of geosciences at Penn State and an author of the study. “Scientists have thought of these as the same thing — the continents became stable and then emerged above sea level. But what we are saying is that those processes are separate.”

Cratons extend more than 150 kilometers, or 93 miles, from the Earth’s surface to the upper mantle — where they act like the keel of a boat, keeping the continents floating at or near sea level across geological time, the scientists said.

Weathering may have ultimately concentrated heat-producing elements like uranium, thorium and potassium in the shallow crust, allowing the deeper crust to cool and harden. This mechanism created a thick, hard layer of rock that may have protected the bottoms of the continents from being deformed later — a characteristic feature of cratons, the scientists said.

“The recipe for making and stabilizing continental crust involves concentrating these heat-producing elements — which can be thought of as little heat engines — very close to the surface,” said Andrew Smye, associate professor of geosciences at Penn State and an author of the study. “You have to do that because each time an atom of uranium, thorium or potassium decays, it releases heat that can increase the temperature of the crust. Hot crust is unstable — it’s prone to being deformed and won’t stick around.”

As wind, rain and chemical reactions broke down rocks on the early continents, sediments and clay minerals were washed into streams and rivers and carried to the sea where they created sedimentary deposits like shales that were high in concentrations of uranium, thorium and potassium, the scientists said.

Collisions between tectonic plates buried these sedimentary rocks deep in the Earth’s crust where radiogenic heat released by the shale triggered melting of the lower crust. The melts were buoyant and ascended back to the upper crust, trapping the heat-producing elements there in rocks like granite and allowing the lower crust to cool and harden.

Cratons are believed to have formed between 3 and 2.5 billion years ago — a time when radioactive elements like uranium would have decayed at a rate about twice as fast and released twice as much heat as today.

The work highlights that the time when the cratons formed on the early middle Earth was uniquely suited for the processes that may have led them to becoming stable, Reimink said.

“We can think of this as a planetary evolution question,” Reimink said. “One of the key ingredients you need to make a planet like Earth might be the emergence of continents relatively early on in its lifespan. Because you’re going to create radioactive sediments that are very hot and that produce a really stable tract of continental crust that lives right around sea level and is a great environment for propagating life.”

The researchers analyzed uranium, thorium and potassium concentrations from hundreds of samples of rocks from the Archean period, when the cratons formed, to assess the radiogenic heat productivity based on actual rock compositions. They used these values to create thermal models of craton formation.

“Previously people have looked at and considered the effects of changing radiogenic heat production through time,” Smye said. “But our study links rock-based heat production to the emergence of continents, the generation of sediments and the differentiation of continental crust.”

Typically found in the interior of continents, cratons contain some of the oldest rocks on Earth, but remain challenging to study. In tectonically active areas, mountain belt formation might bring rocks that had once been buried deep underground to the surface.

But the origins of the cratons remain deep underground and are inaccessible. The scientists said future work will involve sampling ancient interiors of cratons and, perhaps, drilling core samples to test their model.

“These metamorphosed sedimentary rocks that have melted and produced granites that concentrate uranium and thorium are like black box flight recorders that record pressure and temperature,” Smye said. “And if we can unlock that archive, we can test our model’s predictions for the flight path of the continental crust.”

Penn State and the U.S. National Science Foundation provided funding for this work.

END

Rock steady: Study reveals new mechanism to explain how continents stabilized

2024-05-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A new, low-cost, high-efficiency photonic integrated circuit

2024-05-08

The rapid advancement in photonic integrated circuits (PICs), whichcombine multiple optical devices and functionalities on a single chip, has revolutionized optical communications and computing systems.

For decades, silicon-based PICs have dominated the field due to their cost-effectiveness and through their integration with existing semiconductor manufacturing technologies, despite their limitations with regard to their electro-optical modulation bandwidth. Nevertheless, silicon-on-insulator optical transceiver chips were successfully commercialized, driving information traffic through millions of glass fibers in modern datacenters.

Recently, the lithium niobate-on-insulator ...

Mount Sinai scientists unravel how psychedelic drugs interact with serotonin receptors to potentially produce therapeutic benefits

2024-05-08

Researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai have shed valuable light on the complex mechanisms by which a class of psychedelic drugs binds to and activates serotonin receptors to produce potential therapeutic effects in patients with neuropsychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety. In a study published May 8 in Nature, the team reported that certain psychedelic drugs interact with an underappreciated member of the serotonin receptor family in the brain known as 5-HT1A to produce therapeutic benefits in animal models.

“Psychedelics like LSD and psilocybin have entered clinical trials with promising early results, though we still don’t ...

Keck Medicine of USC earns ‘LGBTQ+ Healthcare Equality Leader’ 2024 designation

2024-05-08

LOS ANGELES — Keck Medicine of USC hospitals and USC Student Health, part of Keck Medicine, received the ‘LGBTQ+ Healthcare Equality Leader’ designation in the Human Rights Campaign Foundation’s 2024 Healthcare Equality Index (HEI).

HEI is the leading national benchmarking survey of health care facility policies and practices dedicated to the equitable treatment and inclusion of LGBTQ+ patients, visitors and employees. A record 1,065 health care facilities participated in the 2024 HEI survey; ...

New guidelines for depression care emphasize patient-centred approach

2024-05-08

Psychiatrists and mental health professionals have a new standard for managing major depression, thanks to refreshed clinical guidelines published today by the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT).

The CANMAT guidelines are the most widely used clinical guidelines for depression in the world. The new version integrates the latest scientific evidence and advances in depression care since the previous guidelines were published in 2016. The update was led by researchers at the University of B.C. and the University of Toronto, alongside ...

Children sleep problems associated with psychosis in young adults

2024-05-08

Children who experience chronic lack of sleep from infancy may be at increased risk of developing psychosis in early adulthood, new research shows.

Researchers at the University of Birmingham examined information on nighttime sleep duration from a large cohort study of children aged between 6 months and 7 years old. They found that children who persistently slept fewer hours, throughout this time period, were more than twice as likely to develop a psychotic disorder in early adulthood, and nearly four times as likely to have a psychotic episode.

While ...

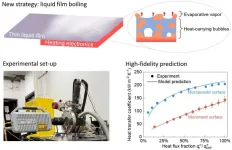

High-fidelity model for designing efficient thermal management surfaces

2024-05-08

In the past decade, fires from electronic devices and batteries, from small smartphones to electrical vehicles and airplanes, have repeatedly made headlines. Enhanced computational power has led to a large amount of waste heat generation and undesirable temperature rise of electronics. Poor heat management is the cause of over half of electronic device failures. To tackle this issue, it is crucial to develop advanced cooling technologies to effectively manage heat and maintain temperatures in the working conditions.

Among various cooling technologies, liquid-vapor phase-change cooling, which utilizes the boiling or evaporation of ...

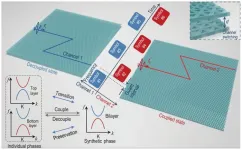

Terahertz flexible multiplexing chip enabled by synthetic topological phase transitions

2024-05-08

This study is led by Prof. Xu (State Key Laboratory of Integrated Optoelectronics, College of Electronic Science and Engineering, Jilin University), Prof. Yu (College of Information Science and Electronic Engineering, Zhejiang University), Prof. Han (Precision Instrument and Optoelectronics Engineering, Key Laboratory of Optoelectronic Information Technology, Tianjin University and Guangxi Key Laboratory of Optoelectronic Information Processing, School of Optoelectronic Engineering, Guilin University of Electronic Technology), and Prof. Sun ...

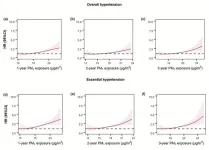

Potential causal effect of long-term PM1 exposure on hypertension hospitalization

2024-05-08

Hypertension is among the leading cardiovascular diseases. Despite extensive research, evidence concerning the relationship between long-term exposure to ambient particulate matter and hypertension remains limited and inconsistent, particularly with regard to submicron particulate matter (PM1). While randomized controlled trials are considered the gold standard for causal inference, environmental epidemiological studies typically rely on observational data. Traditional approaches in observational studies are less effective than randomized controlled trials in fully controlling for confounding factors to achieve results with causal interpretability. With the advancement of causal ...

Vertical atmospheric measurements and simulations demonstrate important contribution of combustion-related ammonium during haze pollution in Beijing

2024-05-08

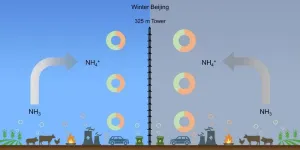

Recently, Science Bulletin published a research conducted by Prof. Pingqing Fu and Dr. Libin Wu from Tianjin University, Peng Wang from Fudan University, and their Chinese and foreign collaborators. They explored the source of ammonium in PM2.5 at different heights of the atmospheric boundary layer in Beijing, and found that combustion-related ammonia is very important to ammonium in PM2.5 during haze pollution in winter.

Air pollution and treatment in Beijing have been widely concerned by both the scientific community and the public. Although its PM2.5 has decreased significantly in the past few years, there is still haze pollution in Beijing, especially in winter. The chemical compositions ...

Simulated High-altitude exposure for 24-hours is well tolerated by adolescents and adults with single-ventricle physiology after Fontan-palliation

2024-05-08

The researchers conducted a study over four days, including overnight stays, with 18 subjects at :envihab, the DLR medical research centre in Cologne. At a simulated altitude of 2500 meters above sea level, the influence of hypoxia (oxygen deficiency) on various hemodynamic and metabolic parameters was investigated. The central venous pressure via a catheter and the blood flow in the lungs using real-time magnetic resonance imaging were evaluated. The results showed that neither the pulmonarypressure nor the blood flow changed significantly. All patients able to tolerate a longer stay at altitude of 24 to 30 hours without complications.

Oxygenation ...