(Press-News.org) In daily life, when two objects are “indistinguishable,” it’s due to an imperfect state of knowledge. As a street magician scrambles the cups and balls, you could, in principle, keep track of which ball is which as they are passed between the cups. However, at the smallest scales in nature, even the magician cannot tell one ball from another. True indistinguishability of this type can fundamentally alter how the balls behave.

For example, in a classic experiment by Hong, Ou and Mandel, two identical photons (balls) striking opposite sides of a half-reflective mirror are always found to exit from the same side of the mirror (in the same cup). This results from a special kind of interference, not any interaction between the photons. For more photons, and more mirrors, this interference becomes enormously complicated.

Measuring the pattern of photons that emerges from a given maze of mirrors is known as “boson sampling.” Boson sampling is believed to be infeasible to simulate on a classical computer for more than a few tens of photons. As a result, there has been a significant effort to perform such experiments with photons and demonstrate that a quantum device is performing a (non-universal) computational task that cannot be performed classically. This effort has culminated in recent claims of quantum advantage using photons.

Now, in a recently published Nature paper, JILA fellow, National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) physicist and University of Colorado Boulder Physics Professor Adam Kaufman and his team, along with collaborators at NIST, have demonstrated a novel method of boson sampling using ultracold atoms (specifically, bosonic atoms) in a two-dimensional optical lattice of intersecting laser beams.

Using tools such as optical tweezers, specific patterns of identical atoms can be prepared. The atoms can be propagated through the lattice with minimal loss, and their positions detected with nearly perfect accuracy after their journey. The result is an implementation of boson sampling that is a significant leap beyond what has been achieved before, either in computer simulations or with photons.

“Optical tweezers have enabled ground-breaking experiments in many-body physics, often for studies of many-interacting atoms, where the atoms are pinned in space and interacting over long distances,” said Kaufman. “However, a large class of foundational many-body problems—so-called ‘Hubbard’ systems—arise when particles can both interact and tunnel, quantum mechanically spreading out in space. Early on in building this experiment, we had the goal of applying this tweezer paradigm to large-scale Hubbard systems— this publication marks the first realization of that vision.”

Techniques for Better Control

To achieve these results, the researchers used several cutting-edge techniques, including optical tweezers—highly focused lasers that can move individual atoms with exquisite precision—and advanced cooling methods that bring the atoms near absolute zero temperature, minimizing their movement and allowing for precise control and measurement.

Similar to how a magnifying glass creates a pinprick of light when focused, optical tweezers can hold individual atoms in powerful beams of light, allowing them to be moved with increased precision. Using these tweezers, the researchers prepared specific patterns of up to 180 strontium atoms in a 1,000-site lattice, formed by intersecting laser beams that create a grid-like pattern of potential energy wells to trap the atoms. The researchers also used sophisticated laser cooling techniques to prepare the atoms, ensuring they remained in their lowest energy state, thereby reducing noise and decoherence—common challenges in quantum experiments.

NIST physicist Shawn Geller explained that the cooling and preparation ensured that the atoms were as identical as possible, removing any labels, such as individualized internal states or motional states, that could make a given atom different from the others. “Adding an additional label means the universe can tell which atom is which, even if you can't see the label as an experimenter,” said first author and former JILA graduate student Aaron Young. “The presence of such a label would change this from an absurdly hard sampling problem to one that's completely trivial.”

A Matter of Scaling

For the same reason that boson sampling is hard to simulate, directly verifying that the correct sampling task has been performed is not feasible for the experiments with 180 atoms. To overcome this issue, the researchers sampled their atoms at various scales.

According to Young, “We do tests with two atoms, where we understand very well what's happening. Then, at an intermediate scale where we can still simulate things, we can compare our measurements to simulations involving reasonable error models for our experiment. At large scale, we can continuously vary how hard the sampling task is by controlling how distinguishable the atoms are and confirm that nothing dramatic is going wrong.”

Geller added: “What we did was develop tests that use physics we know to explain what we think is happening.”

Through this process, the researchers were able to confirm the high fidelity of the atom preparation and evolution in comparison to previous boson sampling demonstrations. In particular, the very low loss of atoms compared to photons during their evolution precludes modern computational techniques that challenge previous quantum advantage demonstrations.

The high quality and programmable preparation, evolution, and detection of atoms in a lattice demonstrated in this work can be applied in the situation where the atoms interact. This opens new approaches simulating and studying the behavior of real, and otherwise poorly understood, quantum materials.

“Using non-interacting particles allowed us to take this specific problem of boson sampling to a new regime,” said Kaufman. “Yet, many of the most physically interesting and computationally challenging problems arise with systems of many interacting particles. Going forward, we expect that applying these new tools to such systems will open the door to many exciting experiments.”

END

The interference of many atoms, and a new approach to boson sampling

2024-05-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

AI and holography bring 3D augmented reality to regular glasses

2024-05-08

Researchers in the emerging field of spatial computing have developed a prototype augmented reality headset that uses holographic imaging to overlay full-color, 3D moving images on the lenses of what would appear to be an ordinary pair of glasses. Unlike the bulky headsets of present-day augmented reality systems, the new approach delivers a visually satisfying 3D viewing experience in a compact, comfortable, and attractive form factor suitable for all-day wear.

“Our headset appears to the outside world just like an everyday pair of glasses, but what the wearer sees through the lenses is an enriched world overlaid with vibrant, full-color 3D computed imagery,” said Gordon ...

Estimated number of children who lost a parent to drug overdose in the US from 2011 to 2021

2024-05-08

About The Study: More than 320,000 children in the U.S. lost a parent to drug overdose between 2011-2021, with significant disparities evident across racial and ethnic groups. Given the potential short- and long-term negative impact of parental loss, program and policy planning should ensure that responses to the overdose crisis account for the full burden of drug overdose on families and children, including addressing the economic, social, educational, and health care needs of children who have lost parents to overdose.

Corresponding Author: To contact the ...

Sexual harassment, abuse, and discrimination in obstetrics and gynecology

2024-05-08

About The Study: The findings of this study suggest that there is a high prevalence of harassment in OB-GYN despite being a predominantly female field for the last decade.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Ankita Gupta, M.D., M.P.H., email ankita.gupta@louisville.edu.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.10706)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, ...

Childhood maltreatment responsible for up to 40 percent of mental health conditions

2024-05-08

A study examining childhood maltreatment in Australia has revealed the shocking burden for Australians, estimating it causes up to 40 percent of common, life-long mental health conditions.

The mental health conditions examined were anxiety, depression, harmful alcohol and drug use, self-harm and suicide attempts. Childhood maltreatment is classified as physical, sexual and emotional abuse, and emotional or physical neglect before the age of 18.

Childhood maltreatment was found to account for 41 percent of suicide attempts in Australia, 35 percent for cases of self-harm and 21 percent for depression.

The ...

Strictly no dancing

2024-05-08

Since the discovery of quantum mechanics more than a hundred years ago, it has been known that electrons in molecules can be coupled to the motion of the atoms that make up the molecules. Often referred to as molecular vibrations, the motion of atoms act like tiny springs, undergoing periodic motion. For electrons in these systems, being joined to the hip with these vibrations means they are constantly in motion too, dancing to the tune of the atoms, on timescales of a millionth of a billionth of a second. But all this dancing around leads ...

Rock steady: Study reveals new mechanism to explain how continents stabilized

2024-05-08

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Ancient, expansive tracts of continental crust called cratons have helped keep Earth’s continents stable for billions of years, even as landmasses shift, mountains rise and oceans form. A new mechanism proposed by Penn State scientists may explain how the cratons formed some 3 billion years ago, an enduring question in the study of Earth’s history.

The scientists reported today (May 8) in the journal Nature that the continents may not have emerged from Earth’s ...

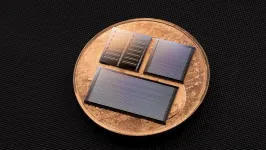

A new, low-cost, high-efficiency photonic integrated circuit

2024-05-08

The rapid advancement in photonic integrated circuits (PICs), whichcombine multiple optical devices and functionalities on a single chip, has revolutionized optical communications and computing systems.

For decades, silicon-based PICs have dominated the field due to their cost-effectiveness and through their integration with existing semiconductor manufacturing technologies, despite their limitations with regard to their electro-optical modulation bandwidth. Nevertheless, silicon-on-insulator optical transceiver chips were successfully commercialized, driving information traffic through millions of glass fibers in modern datacenters.

Recently, the lithium niobate-on-insulator ...

Mount Sinai scientists unravel how psychedelic drugs interact with serotonin receptors to potentially produce therapeutic benefits

2024-05-08

Researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai have shed valuable light on the complex mechanisms by which a class of psychedelic drugs binds to and activates serotonin receptors to produce potential therapeutic effects in patients with neuropsychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety. In a study published May 8 in Nature, the team reported that certain psychedelic drugs interact with an underappreciated member of the serotonin receptor family in the brain known as 5-HT1A to produce therapeutic benefits in animal models.

“Psychedelics like LSD and psilocybin have entered clinical trials with promising early results, though we still don’t ...

Keck Medicine of USC earns ‘LGBTQ+ Healthcare Equality Leader’ 2024 designation

2024-05-08

LOS ANGELES — Keck Medicine of USC hospitals and USC Student Health, part of Keck Medicine, received the ‘LGBTQ+ Healthcare Equality Leader’ designation in the Human Rights Campaign Foundation’s 2024 Healthcare Equality Index (HEI).

HEI is the leading national benchmarking survey of health care facility policies and practices dedicated to the equitable treatment and inclusion of LGBTQ+ patients, visitors and employees. A record 1,065 health care facilities participated in the 2024 HEI survey; ...

New guidelines for depression care emphasize patient-centred approach

2024-05-08

Psychiatrists and mental health professionals have a new standard for managing major depression, thanks to refreshed clinical guidelines published today by the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT).

The CANMAT guidelines are the most widely used clinical guidelines for depression in the world. The new version integrates the latest scientific evidence and advances in depression care since the previous guidelines were published in 2016. The update was led by researchers at the University of B.C. and the University of Toronto, alongside ...