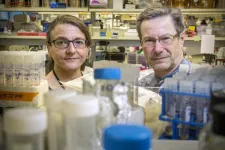

(Press-News.org) A deadly strain of cholera bacteria that emerged in Indonesia back in 1961 continues to spread widely to this day, claiming thousands of lives around the world every year, sickening millions — and, with its persistence, baffling scientists. Finally, in a study published today in Nature, researchers from The University of Texas at Austin have discovered how this dangerous strain has held out over decades.

A longstanding mystery about the strain of Vibrio cholerae (V. cholerae) responsible for the seventh global cholera pandemic is how this lineage has managed to out-compete other pathogenic variants. The UT team identified a unique quirk of the immune system that protects the bacteria from a key driver of bacterial evolution.

“This component of the immune system is unique to this strain, and it has likely given it an extraordinary advantage over other V. Cholerae lineages,” said Jack Bravo, a UT postdoctoral researcher in molecular biosciences and corresponding author on the paper. “It has also allowed it to defend against parasitic mobile genetic elements, which has likely played a key part in the ecology and evolution of this strain and ultimately contributed to the longevity of this pandemic lineage.”

Cholera and other bacteria, like all living things, evolve through a series of mutations and adaptations over time, allowing for new developments in a changing environment, such as antibiotic resistance. Some of the drivers of evolution in microbes are even smaller DNA structures called plasmids that infect, exist and replicate inside a bacterium in ways that can change bacterial DNA. Plasmids also can use up energy and cause mutations that are less advantageous for the bacteria.

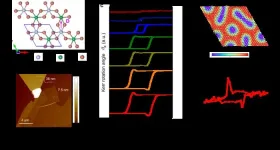

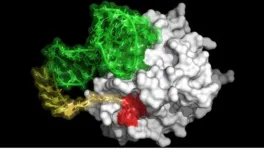

Through a combination of laboratory analysis and cryo-electron-microscope imaging, the research team identified a unique two-part defense system that these bacteria have that essentially destroys plasmids, thus protecting and preserving the bacterial strain.

The World Health Organization estimates that cholera infects 1.3 million to 4 million people a year and that between 21,000 and 143,000 die annually. The bacterium is usually spread through contaminated water and food or contact with an infected person’s fluids. Severe cases are marked by diarrhea, vomiting and muscle cramps that can lead to dehydration, sometimes fatally. Outbreaks occur mostly in areas with poor sanitation and drinking water infrastructure. Although there is currently a vaccine to fight cholera, protection against severe symptoms drops after only three months. With new interventions needed, researchers say their study offers a potential new avenue for drugmakers to explore.

“This unique defense system could be a target for treatment or prevention,” said David Taylor, associate professor of molecular biosciences at UT and an author on the paper. “If we can remove this defense, it could leave it vulnerable, or if we can turn its own immune system back on the bacteria, it would be an effective way to destroy it.”

The defense system outlined in the paper consists of two parts that work together. One protein targets the DNA of plasmids with remarkable accuracy, and a complementary enzyme shreds the DNA of the plasmid, unwinding the helix of the DNA moving in opposite directions.

Researchers noted that this system is also similar to some of the CRISPR-Cascade complexes, which are also based on bacterial immune systems. The CRISPR discovery eventually revolutionized gene-editing technologies that have brought about massive biomedical breakthroughs.

Delisa A. Ramos, Rodrigo Fregoso Ocampo and Caiden Ingram of UT were also authors on the paper. The research was funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) of the National Institutes of Health and a Welch Foundation research grant.

END

Persistent strain of cholera defends itself against forces of change, scientists find

New clues to longstanding mystery about the longest-running cholera epidemic

2024-05-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Rice study reveals insights into protein evolution

2024-05-13

Rice University’s Peter Wolynes and his research team have unveiled a breakthrough in understanding how specific genetic sequences, known as pseudogenes, evolve. Their paper was published May 13 by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America Journal.

Led by Wolynes, the D.R. Bullard-Welch Foundation Professor of Science, professor of chemistry, biosciences and physics and astronomy and co-director of the Center for Theoretical Biological Physics (CTBP), the team focused on deciphering the complex energy landscapes of de-evolved, putative protein sequences corresponding to pseudogenes.

Pseudogenes are ...

Low testosterone in men associated with higher risk for death

2024-05-13

Embargoed for release until 5:00 p.m. ET on Monday 13 May 2024

Annals of Internal Medicine Tip Sheet

@Annalsofim

Below please find summaries of new articles that will be published in the next issue of Annals of Internal Medicine. The summaries are not intended to substitute for the full articles as a source of information. This information is under strict embargo and by taking it into possession, media representatives are committing to the terms of the embargo not ...

Chatbots tell people what they want to hear

2024-05-13

Chatbots share limited information, reinforce ideologies, and, as a result, can lead to more polarized thinking when it comes to controversial issues, according to new Johns Hopkins University–led research.

The study challenges perceptions that chatbots are impartial and provides insight into how using conversational search systems could widen the public divide on hot-button issues and leave people vulnerable to manipulation.

“Because people are reading a summary paragraph generated by AI, they think they’re getting unbiased, fact-based answers,” said lead author Ziang Xiao, an assistant professor of computer ...

Herpes cure with gene editing makes progress in laboratory studies

2024-05-13

SEATTLE — May 13, 2024 — Researchers at Fred Hutch Cancer Center have found in pre-clinical studies that an experimental gene therapy for genital and oral herpes removed 90% or more of the infection and suppressed how much virus can be released from an infected individual, which suggests that the therapy would also reduce the spread of the virus.

“Herpes is very sneaky. It hides out among nerve cells and then reawakens and causes painful skin blisters,” said Keith Jerome, MD, PhD, professor ...

Catch and release can give sea turtles the bends #ASA186

2024-05-13

OTTAWA, Ontario, May 13, 2024 – Six out of seven sea turtle species are endangered, and humans are primarily responsible. Commercial fishing activities are the largest human-caused disturbance to sea turtles due to accidental capture.

Fishers are typically unaware if a sea turtle is caught in their net until it’s completely pulled out of the water. However, releasing sea turtles without veterinary evaluations can be harmful. When accidentally caught, the turtles’ normal diving processes are interrupted, ...

Researchers unveil unique tidal disruption event with unprecedented early optical bump

2024-05-13

A research team from the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) presented a detailed analysis of a tidal disruption event (TDE) with unique characteristics, providing new insights into the behavior of TDEs and their multiwavelength emissions. The study was published online in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

When a star ventures too close to a supermassive black hole at the center of a galaxy, it gets torn apart by the black hole's immense tidal forces, resulting ...

Researchers discover "topological hall effect" in two-dimensional quantum magnets

2024-05-13

In a recent study published in Nature Physics, researchers from the Hefei Institutes of Physical Science of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, together with researchers of University of Science and Technology of China, have introduced the concept of the "Topological Kerr Effect" by using the low-temperature magnetic field microscopy system and the magnetic force microscopy imaging system supported by the steady-state high magnetic field experimental facility.

The study holds great promise for advancing our understanding of topological magnetic ...

Like dad and like mum…all in one plant

2024-05-13

In a new study, led by Charles Underwood from the Max Planck Institute for Plant Breeding Research (MPIPZ) in Cologne, Germany, scientists established a system to generate clonal sex cells in tomato plants and used them to design the genomes of offspring. The fertilization of a clonal egg from one parent by a clonal sperm from another parent led to plants containing the complete genetic information of both parents. The study is now published in Nature Genetics.

Hybrid seeds, combining two different parent lines with specific favorable traits, are popular in agriculture as they give rise to robust crops with enhanced productivity, and have been utilized by farmers ...

New molecule mimics the anti-clotting action of blood-sucking organisms

2024-05-13

DURHAM, N.C. – Nature gave ticks, mosquitos and leaches a quick-acting way to keep blood from clotting while they extract their meal from a host.

Now the key to that method has been harnessed by a team of Duke researchers as a potential anti-clotting agent that could be used as an alternative to heparin during angioplasty, dialysis care, surgeries and other procedures.

Publishing in the journal Nature Communications, the researchers describe a synthetic molecule that mimics the effects of compounds in the saliva of blood-sucking critters. Importantly, the new molecule can also ...

Transgender preteens report 13 hours of daily screen time

2024-05-13

Toronto, ON - A new national study found that transgender preteens, 12 and13 years old, reported 13 hours of daily recreational screen time, which was 4.5 hours more than their cisgender peers. Data were collected from 2019 to 2021, overlapping with the COVID-19 pandemic, and the study was published in Annals of Epidemiology.

“Transgender adolescents are more likely to experience school-based bullying and exclusion from peer groups due to their gender identity, leading them to spend less time in traditional school activities and more time on screens,” says lead author, Jason Nagata, MD, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco. ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

Modular assembly of chiral nitrogen-bridged rings achieved by palladium-catalyzed diastereoselective and enantioselective cascade cyclization reactions

Promoting civic engagement

AMS Science Preview: Hurricane slowdown, school snow days

Deforestation in the Amazon raises the surface temperature by 3 °C during the dry season

Model more accurately maps the impact of frost on corn crops

How did humans develop sharp vision? Lab-grown retinas show likely answer

Sour grapes? Taste, experience of sour foods depends on individual consumer

At AAAS, professor Krystal Tsosie argues the future of science must be Indigenous-led

From the lab to the living room: Decoding Parkinson’s patients movements in the real world

Research advances in porous materials, as highlighted in the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Sally C. Morton, executive vice president of ASU Knowledge Enterprise, presents a bold and practical framework for moving research from discovery to real-world impact

Biochemical parameters in patients with diabetic nephropathy versus individuals with diabetes alone, non-diabetic nephropathy, and healthy controls

Muscular strength and mortality in women ages 63 to 99

[Press-News.org] Persistent strain of cholera defends itself against forces of change, scientists findNew clues to longstanding mystery about the longest-running cholera epidemic