(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA (May 15, 2024)—Immunotherapy has revolutionized the way we treat cancer in recent years. Instead of targeting the tumor itself, immunotherapies work by directing patients’ immune systems to attack their tumors more effectively. This has been especially impactful in improving outcomes for certain difficult-to-treat cancers. Still, fewer than half of all cancer patients respond to current immunotherapies, creating an urgent need to identify biomarkers that can predict which patients are most likely to benefit.

Recently, scientists have noticed that patients whose tumors have a mutation in a gene called ARID1A are more likely to respond positively to immune checkpoint blockade, a type of immunotherapy that works by keeping cancer-fighting immune cells called T cells turned “on” when they’d otherwise be turned “off.” Since this ARID1A gene mutation is present in many cancers—including endometrial, ovarian, colon, gastric, liver, and pancreatic cancers—researchers at the Salk Institute wondered how it contributes to treatment sensitivity, and how clinicians can use this information to customize cancer treatments to each patient.

The new study, published in Cell on May 15, 2024, reveals that ARID1A mutation renders tumors sensitive to immunotherapy by inviting cancer-fighting immune cells into the tumor through an antiviral-like immune response. The researchers suggest this mutation and antiviral immune response could be used as a biomarker to better select patients for specific immunotherapies, like immune checkpoint blockade. The findings also encourage the development of drugs that target ARID1A and related proteins as a way of sensitizing other tumors to immunotherapy.

“This could really make a difference in patient outcomes from cancer treatment,” says Associate Professor Diana Hargreaves, senior author of the study. “These ARID1A mutation cancer patients are already having an immune response, so all we need to do is upregulate that response using immune checkpoint blockade to help them destroy their tumors from the inside.”

While it was reported that people with ARID1A mutations responded well to immune checkpoint blockade, the exact relationship between the two remained unclear. To elucidate the mechanism behind this, Salk scientists turned to mouse models of melanoma and colon cancer with either mutated ARID1A or functional ARID1A.

The team observed a powerful immune response in all animal models with mutated ARID1A tumors but not those with functional ARID1A tumors, supporting the idea that the ARID1A mutation was, indeed, driving the response. But how did this work on a molecular level?

“We found that ARID1A plays an important role in the nucleus of keeping DNA properly arranged,” says Matthew Maxwell, first author of the study and a graduate student in Hargreaves’ lab. “Without functional ARID1A, loose DNA can be excised and escape into the cytosol, which activates a coincidentally desirable antiviral immune response that can be further enhanced by immune checkpoint blockade.”

The ARID1A gene codes for a protein that helps regulate the shape of our DNA and maintain genome stability. When ARID1A is mutated, a microscopic chain of events analogous to a Rube Goldberg machine is set off in the cancer cell. First, the lack of functional ARID1A leads to escape of DNA into the cytosol. Next, the cytosolic DNA activates an antiviral alarm system—the cGAS-STING pathway—since our cells are adapted to flag any DNA in the cytosol as foreign to protect us against viral infections. Finally, the cGAS-STING pathway calls on the immune system to recruit T cells into the tumor and activates them into specialized cancer-killing T cells.

With each step relying on the last, this chain of events—ARID1A mutation, DNA escape, cGAS-STING alarm, T cell recruitment—results in more cancer-fighting T cells in the tumor. Immune checkpoint blockade can then be used to ensure these T cells stay “on,” supercharging them to defeat the cancer.

“Our findings provide a novel molecular mechanism by which ARID1A mutation can promote an anti-tumor immune response,” says Hargreaves. “What’s most exciting about these results is their translational potential. Not only can we use ARID1A mutations to help select patients for immune checkpoint blockade, but we now also see a mechanism by which drugs that inhibit ARID1A or its protein complex could be used to further enhance immunotherapy in other patients.”

By outlining the mechanism by which immune checkpoint blockade is more effective for ARID1A mutant cancers, the researchers have provided cause for clinicians to prioritize the immunotherapy for patients with mutated ARID1A. The findings are a major step in personalizing cancer treatment and inspiring novel therapies that target and inhibit ARID1A and its protein complex.

In the future, the Salk team hopes its findings can improve patient outcomes across the many cancer types associated with ARID1A mutations and is set to explore this clinical translation with collaborators at UC San Diego.

Other authors include Jawoon Yi, Shitian Li, Samuel Rivera, Jingting Yu, Mannix Burns, Helen McRae, Braden Stevenson, Josephine Ho, Kameneff Bojorquez Gastelum, Joshua Bell, Alexander Jones, Gerald Shadel, and Susan Kaech of Salk; Marianne Hom-Tedla and Katherine Coakley of Salk and UC San Diego; Ramez Eskander of UC San Diego; and Emily Dykhuizen of Purdue University.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NCI CCSG P30 014195, T32DK007541, R01 CA228211, R01 CA285867, R01 CA216101, R01 CA240909, R01 AI066232, R21 MH128678, S10-OD023689), National Science Foundation, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Cancer Research Institute, Pew-Stewart Scholars for Cancer Research, American Cancer Society, and Padres Pedal the Cause.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

Unlocking the secrets of life itself is the driving force behind the Salk Institute. Our team of world-class, award-winning scientists pushes the boundaries of knowledge in areas such as neuroscience, cancer research, aging, immunobiology, plant biology, computational biology, and more. Founded by Jonas Salk, developer of the first safe and effective polio vaccine, the Institute is an independent, nonprofit research organization and architectural landmark: small by choice, intimate by nature, and fearless in the face of any challenge. Learn more at www.salk.edu.

END

This time, it’s personal: Enhancing patient response to cancer immunotherapy

Salk researchers uncover why patients with ARID1A mutations are more likely to respond to cancer immunotherapy; findings could improve future cancer care and drug development

2024-05-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A novel multifunctional catalyst turns methane into valuable hydrocarbons

2024-05-15

Methane, a greenhouse gas that contributes significantly towards global warming, is also an important source of energy and an essential chemical resource. When used as a chemical feedstock, methane is typically converted into methanol first and then into hydrocarbons. However, this sequential conversion requires complex industrial setups. More importantly, since methane is a very stable molecule, its conversion into methanol requires tremendous amounts of energy when using conventional means, such ...

Two decades of studies suggest health benefits associated with plant-based diets

2024-05-15

Vegetarian and vegan diets are generally associated with better status on various medical factors linked to cardiovascular health and cancer risk, as well as lower risk of cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and death, according to a new review of 49 previously published papers. Angelo Capodici and colleagues present these findings in the open-access journal PLOS ONE on May 15, 2024.

Prior studies have linked certain diets with increased risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer. A diet that is poor in plant products and rich in meat, refined grains, sugar, and salt is associated with higher risk of death. Reducing consumption of animal-based ...

Bluetooth tracking devices provide new look into care home quality

2024-05-15

Wearable Bluetooth devices can shed light on the care that residents of care homes are receiving and which residents are most in need of social contact, according to a new study published this week in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Carl Thompson of University of Leeds, UK.

In the UK alone, nearly half a million people reside in some form of care home, including long-term care facilities, nursing homes and residential homes. There is no single reliable method that works well to evaluate care home quality, in part because care homes are complex social systems with diverse interacting groups.

In the new study, researchers tested the feasibility of collecting social network ...

Scientists want to know how the smells of nature benefit our health

2024-05-15

Spending time in nature is good for us. Studies have shown that contact with nature can lift our well-being by affecting emotions, influencing thoughts, reducing stress and improving physical health. Even brief exposure to nature can help. One well-known study found that hospital patients recovered faster if their room included a window view of a natural setting.

Knowing more about nature’s effects on our bodies could not only help our well-being, but could also improve how we care for land, preserve ecosystems and design cities, homes and parks. Yet studies on the benefits of contact with nature have typically focused primarily ...

Singing researchers find cross-cultural patterns in music and language

2024-05-15

Language and music may share evolutionary functions. Both speech and song have features such as rhythm and pitch. But are similarities and differences between speech and song shared across cultures?

To investigate this question, 75 researchers—speaking 55 languages—were recruited across Asia, Africa, the Americas, Europe and the Pacific. Among them were experts in ethnomusicology, music psychology, linguistics, and evolutionary biology. The researchers were asked to sing, perform instrumentals, ...

Killer whales breathe just once between dives, study confirms

2024-05-15

A new study has confirmed a long-held assumption: that orcas take just one breath between dives.

The researchers used drone footage and biological data from tags suction-cupped to 11 northern and southern resident killer whales off the coast of B.C. to gather information on the animals’ habits.

Whaley fun facts

Published in PLOS ONE, the study found that residents spend most of their time making shallow dives, with the majority of dives less than one minute. The longest dive recorded was 8.5 minutes, for an adult male. “Killer whales are like sprinters who don’t have the marathon endurance of blue and humpback whales to make deep and prolonged dives,” ...

Bees and butterflies on the decline in western and southern North America

2024-05-15

Bee and butterfly populations are in decline in major regions of North America due to ongoing environmental change, and significant gaps in pollinator research limit our ability to protect these species, according to a study published May 15, 2024 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Sara Souther of Northern Arizona University, US, and colleagues.

Recent research has detected declines in populations of pollinator species, sparking alarm from scientists and policymakers concerned about negative impacts on ecosystems and agriculture. These declines have been linked to various factors including climate change, habitat loss, and invasive species, but ...

Singing researchers investigate cross-cultural patterns in music, language

2024-05-15

Seventy-five researchers from 46 countries recorded themselves performing traditional music and speaking in their own languages in a novel experiment investigating cross-cultural differences and similarities.

With rare exceptions, the rhythms of songs and instrumental melodies were slower than for speech, while the pitches were higher and more stable, according to the study published in Science Advances.

Unique for the number of languages represented – 55 – and the diversity of the researchers, the study provides “strong evidence for cross-cultural regularities,” according to senior author Dr Patrick ...

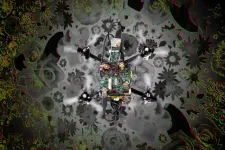

Animal brain inspired AI game changer for autonomous robots

2024-05-15

A team of researchers at Delft University of Technology has developed a drone that flies autonomously using neuromorphic image processing and control based on the workings of animal brains. Animal brains use less data and energy compared to current deep neural networks running on GPUs (graphic chips). Neuromorphic processors are therefore very suitable for small drones because they don’t need heavy and large hardware and batteries. The results are extraordinary: during flight the drone’s deep neural network processes data up to 64 times faster and consumes three times less energy than when running on a GPU. Further developments of this technology may ...

Summers warm up faster than winters, fossil shells from Antwerp show

2024-05-15

Niels de Winter, affiliated with the Department of Earth Sciences at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and the AMGC research group at Vrije Universiteit Brussel, measured alongside colleagues from institutions such as the Institute for Natural Sciences in Brussels the chemical composition of fossil shells from Antwerp, Belgium. Those shells originate from molluscs such as oysters, cockles, and scallops found during the construction works of the Kieldrecht Lock. The molluscs lived lived during the Pliocene, approximately ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Study: Discontinuing antidepressants in pregnancy nearly doubles risk of mental health emergencies

Bipartisan members of congress relaunch Congressional Peripheral Artery Disease (PAD) Caucus with event that brings together lawmakers, medical experts, and patient advocates to address critical gap i

Antibody-drug conjugate achieves high response rates as frontline treatment in aggressive, rare blood cancer

Retina-inspired cascaded van der Waals heterostructures for photoelectric-ion neuromorphic computing

Seashells and coconut char: A coastal recipe for super-compost

Feeding biochar to cattle may help lock carbon in soil and cut agricultural emissions

Researchers identify best strategies to cut air pollution and improve fertilizer quality during composting

International research team solves mystery behind rare clotting after adenoviral vaccines or natural adenovirus infection

The most common causes of maternal death may surprise you

A new roadmap spotlights aging as key to advancing research in Parkinson’s disease

Research alert: Airborne toxins trigger a unique form of chronic sinus disease in veterans

University of Houston professor elected to National Academy of Engineering

UVM develops new framework to transform national flood prediction

Study pairs key air pollutants with home addresses to track progression of lost mobility through disability

Keeping your mind active throughout life associated with lower Alzheimer’s risk

TBI of any severity associated with greater chance of work disability

Seabird poop could have been used to fertilize Peru's Chincha Valley by at least 1250 CE, potentially facilitating the expansion of its pre-Inca society

Resilience profiles during adversity predict psychological outcomes

AI and brain control: A new system identifies animal behavior and instantly shuts down the neurons responsible

Suicide hotline calls increase with rising nighttime temperatures

What honey bee brain chemistry tells us about human learning

Common anti-seizure drug prevents Alzheimer’s plaques from forming

Twilight fish study reveals unique hybrid eye cells

Could light-powered computers reduce AI’s energy use?

Rebuilding trust in global climate mitigation scenarios

Skeleton ‘gatekeeper’ lining brain cells could guard against Alzheimer’s

HPV cancer vaccine slows tumor growth, extends survival in preclinical model

How blood biomarkers can predict trauma patient recovery days in advance

People from low-income communities smoke more, are more addicted and are less likely to quit

No association between mRNA COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy and autism in children, new research shows

[Press-News.org] This time, it’s personal: Enhancing patient response to cancer immunotherapySalk researchers uncover why patients with ARID1A mutations are more likely to respond to cancer immunotherapy; findings could improve future cancer care and drug development