(Press-News.org)

BEER-SHEVA, Israel, May 20, 2024 – When you disable the brakes on a race car, it quickly crashes. Dr. Barak Rotblat wants to do something similar to brain cancer cells. He wants to disable their ability to survive glucose starvation. In fact, he wants to speed the tumor cells up, so they just as quickly die out. It is a novel approach to brain cancer based on a decade of research in his lab.

He and his students' and co-lead researcher Gabriel Leprivier of the Institute of Neuropathology at University Hospital Düsseldorf findings were just published in Nature Communications last week.

Until now, it was believed that cancer cells prioritized growth and rapid proliferation. However, it has been shown that there is less glucose in tumors vs. normal tissue. If cancer cells are solely focused on reproducing at the fastest possible rate, then they should be more dependent on glucose than regular cells. However, what if their absolute top priority is survival rather than exponential growth? Then, triggering a burst of growth under glucose starvation could lead to the cell running out of energy to survive and dying out.

"It is an intriguing insight that comes after a decade of research," explains Dr. Rotblat, "we may be able to target just the cancer cells and not regular cells at all, which would be a very promising step forward on the path to personalized medicine and therapeutics that do not affect healthy cells the way chemotherapy and radiation do."

"Our discovery about glucose starvation and the role of antioxidants opens a therapeutic window to pursue a molecule which could treat glioma (brain cancer)," he adds. Such a therapeutic might also be able to treat other types of cancers.

Rotblat and his students, Dr. Tal Levy and Dr. Khawla Alasad began by considering that cells regulate their growth according to their available energy. When energy is plentiful, cells make fat and lots of proteins to store energy and grow. When energy is scarce, they must pump the brakes and stop making fat and proteins or burn themselves out.

Tumors are mostly in a de facto state of glucose starvation. So, they began thinking about locating the molecular brakes that enable the cancer cell's survival in glucose starvation. If they could turn that off, then the tumor would die, but the regular cells, which are not glucose-starved, would remain unaffected.

So, Rotblat and his students followed the trail of a mTOR (Mamelian Target of Rapamycin) pathway. A pathway equipped with proteins that measure the energetic state of the cell and, accordingly, regulate cell growth. They found that a protein in the mTOR pathway, known to pump the brakes on protein synthesis when energy drops, 4EBP1, is essential for human, mouse, and even yeast cells, to survive glucose starvation. They demonstrated that 4EBP1 does so by negatively regulating the levels of a critical enzyme in the fatty acid synthesis pathway, ACC1. This mechanism is exploited by cancer cells, particularly brain cancer cells, to survive in tumor tissue and generate aggressive tumors.

Dr. Rotblat is now working with BGN Technologies and the National Institute for Biotechnology in the Negev to develop a molecule that will block 4EBP1 forcing glucose-starved tumor cells to keep making fat and burn themselves out when they are glucose-starved.

This work was supported by funds from the Israel Cancer Association (grant no. 20220143), the Israel Science Foundation (grant no. 1436/19) and the NIBN; the Dr. Rolf M. Schwiete Stiftung (grant no. 2020-018); the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant no. LE 3751/2-1), the German Cancer Aid (grants no. 70112624 and 70115129), the Elterninitiative Düsseldorf e.V. (grant no. 701910003), and the Research Commission of the Medical Faculty, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf (grants no. 2016-056 and 2020-044); the Matthias-Lackas foundation, the Dr. Leopold und Carmen Ellinger foundation, the European Research Council (ERC CoG 2023 #101122595), Dr. Rolf M. Schwiete foundation (2021-007, 2022-31), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG 458891500), the German Cancer Aid (DKH-7011411, DKH-70114278, DKH-70115315, DKH-70115914), the SMARCB1 association, the Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF; SMART-CARE and HEROES-AYA), the Fight Kids Cancer foundation (FKC-NEWtargets), the KiTZ-Foundation in memory of Kirstin Diehl, the KiTZ-PMC twinning program, the German Cancer Consortium (DKTK, PRedictAHR), and the Barbara and Wilfried Mohr foundation; the German Cancer Aid (DKH-70114131) and the German Academic Scholarship Foundation; the European Research Council under the ERC Consolidator Grant Agreement n. 771486–MetaRegulation, FWO—Research Projects (G098120N and G0B4122N), KU Leuven—FTBO (ENN-OZFTBO-P7015), King Baudouin Foundation (2021-J1990112-22260), Beug Foundation (Metastasis Prize 2021) and Fonds Baillet Latour (Grant for Biomedical Research 2020).

END

A sweeping new Health Blueprint for Southwest Virginia highlights the grave health challenges that grip the rural region but also proposes solutions to help residents live longer, healthier lives.

The Blueprint was assembled by the University of Virginia College at Wise’s Healthy Appalachia Institute, the Southwest Virginia Health Authority, UVA Health’s Center for Telehealth and a coalition of residents and regional healthcare providers. The document identifies priority health concerns for the three health districts in the southwestern corner of Virginia: Lenowisco, Cumberland Plateau and Mount Rogers. These are areas ...

About The Study: Many studies suggest a survival benefit for cancer trial participants. However, these benefits were not detected in studies using designs addressing important sources of bias and confounding. Pooled results of high-quality studies are not consistent with a beneficial effect of trial participation on its own.

Quote from corresponding author Jonathan Kimmelman, Ph.D.:

“Many physicians, policymakers, patient advocates, and research sponsors believe patients have better outcomes when they participate in trials, even if they are in the comparator arm. Educational ...

Fukuoka, Japan—From the rain drops rolling down your window, to the fluid running across a COVID rapid test, we cannot go a day without observing the world of fluid dynamics. Naturally, how liquids traverse across, and through, surfaces are a heavily researched subject, where new discoveries can have profound effects in the fields of energy conversion technology, electronics cooling, biosensors, and micro-/nano-fabrications.

Now, using mathematical modeling and experimentation, researchers from Kyushu University’s Faculty of Engineering have expanded on a fundamental principle in fluid dynamics. Their new findings may ...

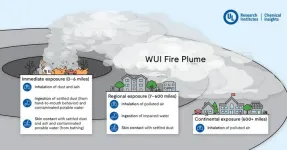

ATLANTA - Chemical Insights Research Institute (CIRI) of UL Research Institutes applies cutting edge technologies to evaluate the toxicity of burn-impacted land areas affected by the August 2023 Lahaina wildfires. Created with CIRI research partners from Duke University and the East-West Center (EWC) in Hawai’i, the study known as Lahaina Environmental Assessment Project (LEAP), will collect and analyze residual dust, soil and ash samples from properties affected by the fires. These residues, including fine dust, ...

PLYMOUTH MEETING, PA [May 20, 2024] — The National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) today announced publication of new NCCN Guidelines for Patients®: Small Bowel Adenocarcinoma. This free resource for people facing cancer and caregivers is focused on a rare cancer type that typically occurs in the small intestine, where routine screening is impossible, even for high-risk individuals. The small amount of patient information that exists for this cancer type tends to combine it with other cancers of the small intestine (such as sarcomas, neuroendocrine tumors, or lymphomas) despite very different treatment approaches and results.

The NCCN Guidelines for Patients: ...

Groundbreaking research has provided new insight into the tectonic plate shifts that create some of the Earth’s largest earthquakes and tsunamis.

“This is the first study to employ coastal geology to reconstruct the rupture history of the splay fault system,” said Jessica DePaolis, postdoctoral fellow in Virginia Tech's Department of Geosciences. “These splay faults are closer to the coast, so these tsunamis will be faster to hit the coastline than a tsunami generated only from ...

In 2023, Antarctic sea ice reached historically low levels, with over 2 million square kilometres less ice than usual during winter – equivalent to about ten times the size of the UK. This drastic reduction followed decades of steady growth in sea ice up to 2015, making the sudden decline even more surprising.

Using a large climate dataset called CMIP6, BAS researchers investigated this unprecedented sea ice loss. They analysed data from 18 different climate models to understand the probability of such a significant reduction in sea ice and its connection to climate change.

Lead author Rachel Diamond explained that while 2023's extreme ...

For hundreds of years, the whitespotted eagle ray (Aetobatus narinari) has been considered the only inshore stingray species in Bermuda, until now.

Using citizen science, photographs, on-water observations and the combination of morphological and genetic data, researchers from Florida Atlantic University’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute and collaborators are the first to provide evidence that the Atlantic cownose ray (Rhinoptera bonasus) has recently made a new home in Bermuda.

Because ...

For many patients with a deadly type of brain cancer called glioblastoma, chemotherapy resistance is a big problem.

Current standard treatments, including surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy using the drug temozolomide, have limited effectiveness and have not significantly changed in the past five decades. Although temozolomide can initially slow tumor progression in some patients, typically the tumor cells rapidly become resistant to the drug.

But now, Virginia Tech researchers with the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC may ...

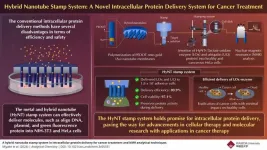

In today's medical landscape, precision medicine and targeted therapies are gaining traction for their ability to tailor treatments to individual patients while minimizing adverse effects. Conventional methods, such as gene transfer techniques, show promise in delivering therapeutic genes directly to cells to address various diseases. However, these methods face significant drawbacks, hindering their efficacy and safety.

Intracellular protein delivery offers a promising approach for developing safer, more targeted, and effective therapies. By directly transferring proteins into target cells, this method circumvents issues such as silencing ...