(Press-News.org) New MBARI research on a field of pockmarks—large, circular depressions on the seafloor—offshore of Central California has revealed that powerful sediment flows, not methane gas eruptions, maintain these prehistoric formations. A team of researchers from MBARI, the United States Geological Survey (USGS), and Stanford University published their findings today in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface. This work provides important information to guide decision-making about responsible use and management of the seafloor off California, including site assessments for the development of offshore wind farms.

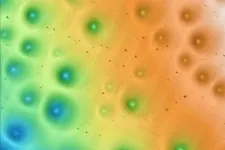

The Sur Pockmark Field—an area about the size of the city of Los Angeles that is located off the coast of Big Sur, California—contains more than 5,200 circular depressions. These formations are approximately 200 meters (656 feet) across, roughly the distance of two football fields, and five meters (16 feet) deep. Past research in other parts of the world has suggested that similar large seafloor depressions were formed and maintained by methane gas bubbling up through the sediments. With wind farms slated for construction offshore of Central California, resource managers were concerned about how the presence of methane gas might impact the stability of the seafloor in this region.

The data collected by MBARI researchers and their collaborators found no evidence of methane at this site. Instead, the research team has proposed that sediment gravity flows—similar to an avalanche of mud, sand, and water moving along the seafloor—that have occurred in this region intermittently for hundreds of thousands of years maintain these seafloor formations.

“There are many unanswered questions about the seafloor and its processes,” said MBARI Senior Research Technician Eve Lundsten, who led this work. “This research provides important data about the seafloor for resource managers and others considering potential offshore sites for underwater infrastructure to guide their decision-making.”

The research team deployed MBARI’s advanced underwater robots to study the Sur Pockmark Field. First, autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs)—torpedo-shaped, self-guided robots—mapped the region. Previous maps of the seafloor were collected by sonar mounted on ships, but the distance between the ocean surface and the seafloor resulted in low-resolution data. AUVs can travel closer to the seafloor to visualize the terrain below in much greater detail. MBARI’s seafloor mapping AUVs also carried technology to profile the sub-bottom layers of sediment below the seafloor. These maps then guided sampling with MBARI’s remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Doc Ricketts. Operated by the research team in the control room aboard an MBARI research vessel, the ROV Doc Ricketts collected sediment samples to reconstruct the history of individual pockmarks.

These pockmarks are located on the continental margin, a dynamic section of the seafloor that connects the relatively shallow continental shelf to the deep sea. Sediment gravity flows can move massive amounts of material through this region intermittently. The data and samples collected by MBARI technology helped the research team piece together the history of sediment movements over this part of the seafloor.

The team found multiple layers of sandy deposits, called turbidites, in the sediment samples taken from the pockmarks and the sub-bottom images of the pockmark field. These deposits indicated that large sediment gravity flows in the region have occurred intermittently for at least the last 280,000 years. These sediment gravity flows appear to cause erosion in the center of each pockmark, maintaining these unique underwater morphologic features over time.

“We collected a massive amount of data, allowing us to make a surprising link between pockmarks and sediment gravity flows. We were unable to determine exactly how these pockmarks were initially formed, but with MBARI’s advanced underwater technology, we’ve gained new insight into how and why these features have persisted on the seafloor for hundreds of thousands of years,” said Lundsten.

Seafloor pockmarks have been found elsewhere around the world. In those locations, pockmarks have been associated with the release of methane gas or other fluids from the seafloor. Bubbling methane could potentially cause the seafloor to be unstable, which could pose risks for structures on the seafloor, like the anchors for offshore wind turbines. In October 2018, the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) announced areas offshore of Central California for potential wind energy leasing. MBARI quickly moved to conduct this research to answer critical questions about the stability of the seafloor to guide development of offshore wind energy in California.

“Expanding renewable energy is critical to achieving the dramatic cuts in carbon dioxide emissions needed to prevent further irreversible climate change. However, there are still many unanswered questions about the possible environmental impacts of offshore wind energy development,” said MBARI President and CEO Chris Scholin. “This research is one of many ways that MBARI researchers are answering fundamental questions about our ocean to help inform decisions about how we use marine resources.”

Because of the extensive efforts of MBARI, USGS, BOEM, and NOAA as part of the interagency Expanding Pacific Research and Exploration of Submerged Systems (EXPRESS) cooperative research campaign, the Sur Pockmark Field is now one of the best-studied areas of seafloor on the west coast of North America. However, there are still many questions to answer about these pockmarks, including how these features were initially formed hundreds of thousands of years ago.

Funding for this work was provided by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, BOEM, and USGS.

Background

The seafloor plays an important ecological and societal role. It provides vital habitat for marine life and supports our modern infrastructure. However, we still have a lot to learn about seafloor processes. MBARI has an active research program that uses advanced robots to study and map the seafloor offshore of Central California. MBARI’s Continental Margin Processes Team, led by Senior Scientist Charlie Paull, investigates how the morphology of the continental margin—where the continental shelf transitions to the abyssal plain—is sculpted and changed over time.

The Sur Pockmark Field is located offshore of Big Sur, California, along the continental margin at a depth of 500 to 1,500 meters (approximately 1,600 to 5,200 feet). Some of these pockmarks were initially discovered by MBARI scientists in 1998 during a seafloor survey using ship-mounted multibeam sonar. Additional ship surveys conducted by MBARI collaborators at the USGS and NOAA in 2018 showed that the pockmarks extend southward into the region off Morro Bay. These surveys have revealed more than 5,200 pockmarks spread out over 1,300 square kilometers (500 square miles), making this area the largest known pockmark field in North America.

The seafloor offshore of this remote stretch of the Central California coastline has historically been one of the least-studied regions of the continental margin off the west coast of North America. For the past six years, MBARI’s Continental Margin Processes Team has been working to understand the origins of the pockmark formations, establish whether they are geologically active, and determine if they are areas of special biological significance.

Past research by MBARI, BOEM, and USGS examined the biological communities within the Sur Pockmark Field. This new research aimed to understand the geological processes that form and maintain pockmarks within the field.

The research team used mapping AUVs developed by engineers in MBARI’s Seafloor Mapping Lab to visualize a portion of the Sur Pockmark Field in greater detail.

Bathymetric surveys by these underwater robots mapped 317 of the 5,251 pockmarks at one-meter resolution. At this fine resolution, it became apparent the pockmarks have very smooth, gradually-sloped sides. The pockmarks are on average 156 meters (512 feet) across, nearly circular in shape, and fairly evenly spaced apart. Additionally, the AUVs were outfitted with a chirp sub-bottom profiler that uses sound to reveal layers of sediment below the seafloor surface. Chirp profiles captured portions of the subsurface below approximately 200 pockmarks at the site.

These surveys captured an assortment of detailed seafloor data that would not be visible from ship-based mapping with multibeam sonar. That data allowed targeted sampling of pockmarks within the field.

The Continental Margin Processes Team conducted 30 dives with two of MBARI’s ROVs to get a closer look at 21 pockmarks within the field. The team recorded 185 hours of seafloor video footage inside and adjacent to pockmarks. MBARI’s ROV Doc Ricketts also collected 107 vibracores—a 1.5-meter (five-foot) core of sediment dislodged into a metal tube by high-frequency vibrations—and 433 pushcores—a shallower 24-centimeter (9.4-inch) sample of sediment—within and around five pockmarks.

A USGS cruise on the research vessel M/V Bold Horizon in 2019 collected deeper piston and gravity cores up to 7.5 meters (25 feet) in length. The piston cores were taken inside pockmarks and at background sites adjacent to but outside of the pockmarks for comparison.

Importantly, the research team found no evidence of methane gas in any of the samples or data that they collected. Instead, the subsurface profiles and sediment samples indicated that the pockmarks contain alternating layers of fine and coarse sediment.

The sandy deposits, or turbidites, were the key to unlocking the surprising story of massive sediment gravity flows passing over the whole area. Fine sediment on the seafloor was deposited slowly over time, then intermittent large sediment gravity flows left a characteristic layer of coarse sand. It appears these flows erode the pockmark centers, leaving behind sandy deposits across multiple pockmarks in the region at the same time.

Scientists have only recently begun to understand the patterns of erosion and deposition by sediment gravity flows in underwater canyons and channels. The Sur Pockmark Field is bordered by two channels—the Lucia Chica Channel to the north and the San Simeon Channel to the south—but is otherwise broad and open terrain.

Exactly how currents and sediments move over the dimpled surface of the Sur Pockmark Field is still unknown. However, the research team has proposed the unique seafloor morphology in this area may create flow patterns that erode the pockmark centers. In this region, sediment gravity flows are episodic, occurring tens of thousands of years apart. The last one was approximately 14,000 years ago. Computer modeling will be required to confirm if an unconfined flow passing over the pockmark field carries sufficient energy to erode and maintain the pockmarks.

END

New research reveals that prehistoric seafloor pockmarks off the California coast are maintained by powerful sediment flows

Data from MBARI’s advanced underwater robots point to erosion during intermittent sediment flows as the mechanism maintaining these circular depressions for hundreds of thousands of years.

2024-05-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

AI can help improve ER admission decisions, Mount Sinai study finds

2024-05-21

New York, NY [May 21, 2024]—Generative artificial intelligence (AI), such as GPT-4, can help predict whether an emergency room patient needs to be admitted to the hospital even with only minimal training on a limited number of records, according to investigators at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Details of the research were published in the May 21 online issue of the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association (JAMIA/DOI: 10.1093/jamia/ocae103).

In the retrospective study, the researchers analyzed records from seven Mount Sinai Health System hospitals, using both structured data, such as vital signs, ...

Matcha mouthwash inhibits bacteria that causes periodontitis

2024-05-21

Highlights:

Periodontitis is linked to tooth loss and other health concerns.

Past studies suggest that green tea products can act against P. gingivalis, which causes periodontitis.

In a new study, researchers tested matcha extract, made from green tea, against the pathogen.

Lab studies suggest matcha inhibits the growth of the bacteria.

A clinical trial showed that matcha mouthwash inhibited P. gingivalis populations in saliva.

Washington, D.C.—Periodontitis is an inflammatory gum disease driven by bacterial infection and left untreated it can lead to complications including tooth loss. ...

Oncology events in Poland solidify collaboration with NCCN

2024-05-21

WARSAW, POLAND [May 21, 2024] — The National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®)—a global nonprofit responsible for leading cancer treatment guidelines—is taking part in two events in Warsaw focused on advancing cancer care and highlighting the Poland-US bilateral achievements in health care from May 21-22, 2024. The meetings will be organized by Maria Sklodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology, the Polish Oncological Society, and the Alliance for Innovation. ...

City of Hope awarded $5.4 million CIRM grant to create a stem cell laboratory and expand access to state-of-the-art disease models and technology among a diverse scientific community

2024-05-21

LOS ANGELES — City of Hope®, one of the largest cancer research and treatment organizations in the United States, has been awarded $5.4 million from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) to build and fund a stem cell research laboratory on its Duarte, California, campus that will further expand its scientific capabilities.

The mission of the unique Stem Cell-Based Disease Modeling Laboratory is two-fold. First, it will advance stem cell-based disease modeling to spur innovation in regenerative medicine. The laboratory leverages City of Hope’s infrastructure ...

Meeting preview: Hot topics at NUTRITION 2024

2024-05-21

Thousands of top nutrition experts will gather next month for a dynamic program of research announcements, policy discussions and award lectures at NUTRITION 2024, the annual flagship meeting of the American Society for Nutrition. Reporters and bloggers are invited to apply for a complimentary press pass to attend the meeting in Chicago from June 29–July 2.

Explore the meeting schedule and register for a press pass to attend.

Hot topics to be explored at NUTRITION 2024 include:

Diet and cancer ...

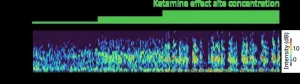

Study models how ketamine’s molecular action leads to its effects on the brain

2024-05-21

A World Health Organization Essential Medicine, ketamine is widely used at varying doses for sedation, pain control, general anesthesia and as a therapy for treatment-resistant depression. While scientists know its target in brain cells and have observed how it affects brain-wide activity, they haven’t known entirely how the two are connected. A new study by a research team spanning four Boston-area institutions uses computational modeling of previously unappreciated physiological details to fill that gap and offer new insights into how ketamine works.

“This modeling work has helped decipher likely mechanisms through which ...

A diaspora-based model of human migration

2024-05-21

How do migrants choose their destinations? Existing models, known as “gravity models,” use population size and travel distance as explanatory variables—and often fail, especially at the neighborhood scale. Many migrants prefer to move to a location near friends, family, or co-nationals. This pattern might be partly driven by factors that repeat (such as the cost of living) and partly driven by homophily, the tendency to interact with similar others. Early migrants tend to reduce uncertainty and provide information for later arrivals. Building on these observations, Rafael Prieto-Curiel and colleagues construct a migration model based on the power of the diaspora to ...

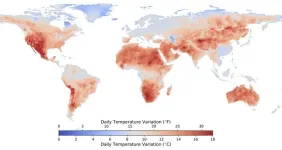

Black and Hispanic Americans experience wider temperature swings

2024-05-21

Extreme heat can harm human health, but so can temperature extreme swings. Large daily temperature variation (DTV) has been associated with elevated mortality in studies around the world. Trees and other vegetation can lower DTV, as trees reduce temperature through transpiration during the day and also trap long-wave radiation in the atmosphere under the canopy at night, increasing temperature. But green space is not equally distributed in most cities. Shengjie Liu and Emily Smith-Greenaway examined inequality in DTV exposure in the US, using monthly nighttime and daytime land surface temperature data from satellites. ...

Gamers say they hate ‘smurfing,’ but admit they do it

2024-05-21

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Online video game players believe the behavior known as “smurfing” is generally wrong and toxic to the gaming community – but most admit to doing it and say some reasons make the behavior less blameworthy, new research finds.

The new study suggests that debates about toxicity in gaming may sometimes be more complex and nuanced than is often acknowledged, according to the researchers.

Online video games use what are called “matchmaking systems” to pair players based on skill. “Smurfing” is when players cheat these systems by creating new accounts so that they can play against people lower ...

How immune cells recognize the abnormal metabolism of cancer cells

2024-05-21

When cells become tumor cells, their metabolism changes fundamentally. Researchers at the University of Basel and the University Hospital Basel have now demonstrated that this change leaves traces that could provide targets for cancer immunotherapies.

Cancer cells function in turbo mode: Their metabolism is programmed for rapid proliferation, whereby their genetic material is also constantly copied and translated into proteins. As researchers led by Professor Gennaro De Libero from the University of Basel and the University ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Pregnancy complications impact women’s stress levels and cardiovascular risk long after delivery

Spring fatigue cannot be empirically proven

Do prostate cancer drugs interact with certain anticoagulants to increase bleeding and clotting risks?

Many patients want to talk about their faith. Neurologists often don't know how.

AI disclosure labels may do more harm than good

The ultra-high-energy neutrino may have begun its journey in blazars

Doubling of new prescriptions for ADHD medications among adults since start of COVID-19 pandemic

“Peculiar” ancient ancestor of the crocodile started life on four legs in adolescence before it began walking on two

AI can predict risk of serious heart disease from mammograms

New ultra-low-cost technique could slash the price of soft robotics

Increased connectivity in early Alzheimer’s is lowered by cancer drug in the lab

Study highlights stroke risk linked to recreational drugs, including among young users

Modeling brain aging and resilience over the lifespan reveals new individual factors

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

[Press-News.org] New research reveals that prehistoric seafloor pockmarks off the California coast are maintained by powerful sediment flowsData from MBARI’s advanced underwater robots point to erosion during intermittent sediment flows as the mechanism maintaining these circular depressions for hundreds of thousands of years.