(Press-News.org) No parent wants to risk their child having a serious infection, least of all while still in the womb, but did you know that the immune response to a viral infection during pregnancy could also affect the development of the unborn offspring? Scientists from Harvard University in Cambridge, USA, have shown that immune reactions in pregnant mice are detected by a specific type of brain cell in the developing embryo and alter how genes are regulated in the brain – a change that persists in juvenile mice. Published today in the journal Development, this study provides new insights into how the maternal immune response might influence brain development in embryos and could help researchers understand the origins of neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism.

Scientists have long suspected that fetal exposure to infectious bugs may increase the risk of developing neurological conditions such as schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders. There is also evidence that fighting infection while pregnant might affect the growth of offspring in the uterus, even if embryos do not become infected themselves. However, it has been unclear how embryos recognise their parent’s immune response and the exact consequences for their development.

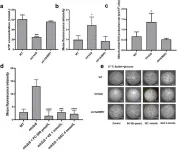

In their latest study, a group at Harvard University led by Professor Paola Arlotta have identified a specific cell type in the mouse embryonic brain that responds to an immune response in the mother. The researchers used a compound that mimics a virus to stimulate an immune response in pregnant mice without causing an actual infection. They then characterised how cells in the embryonic brain respond by assessing which genes were turned on or off. Using this approach, the scientists showed that cells called ‘microglia’ can sense the maternal immune response. “Microglia are the immune cells of the brain. They play a critical role during inflammation and infection and also have fundamental functions in healthy brain development,” explained Arlotta.

Following the mother’s immune response, embryonic microglia change which genes are activated or inactivated, which also occurs in the surrounding brain cells, such as neurons. Interestingly, the change of gene regulation in neighbouring cells depends on microglia being present in the brain; when the researchers repeated the experiments using mice without microglia, the other brain cells did not react to the maternal immune response.

Although most viral infections are often short-lived, the scientists found that the changes that the maternal immune system causes in embryonic brain cells persist well after the immune reaction has subsided. “Based on previous studies demonstrating that microglia exposed to early infections respond differently to stimuli in adulthood, we hypothesized that the maternal immune response could induce changes in microglial gene regulation that persist postnatally” said Dr. Bridget Ostrem, co-author of the study.

This research enhances our understanding of the cellular basis of neurodevelopmental disorders in humans. “Our results suggest a potential role for microglia as therapeutic targets in the setting of maternal infections,” said Ostrem, although there is still more work to be done. Harvard researcher Dr. Nuria Domínguez-Iturza added, “next, it will be crucial to determine the long-term behavioral implications of the changes we observed in this study.”

No parent wants to risk their child having a serious infection, least of all while still in the womb, but did you know that the immune response to a viral infection during pregnancy could also affect the development of the unborn offspring? Scientists from Harvard University in Cambridge, USA, have shown that immune reactions in pregnant mice are detected by a specific type of brain cell in the developing embryo and alter how genes are regulated in the brain – a change that persists in juvenile mice. Published today in the journal Development, this study provides new insights into how the maternal immune response might influence brain development in embryos and could help researchers understand the origins of neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism.

Scientists have long suspected that fetal exposure to infectious bugs may increase the risk of developing neurological conditions such as schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders. There is also evidence that fighting infection while pregnant might affect the growth of offspring in the uterus, even if embryos do not become infected themselves. However, it has been unclear how embryos recognise their parent’s immune response and the exact consequences for their development.

In their latest study, a group at Harvard University led by Professor Paola Arlotta have identified a specific cell type in the mouse embryonic brain that responds to an immune response in the mother. The researchers used a compound that mimics a virus to stimulate an immune response in pregnant mice without causing an actual infection. They then characterised how cells in the embryonic brain respond by assessing which genes were turned on or off. Using this approach, the scientists showed that cells called ‘microglia’ can sense the maternal immune response. “Microglia are the immune cells of the brain. They play a critical role during inflammation and infection and also have fundamental functions in healthy brain development,” explained Arlotta.

Following the mother’s immune response, embryonic microglia change which genes are activated or inactivated, which also occurs in the surrounding brain cells, such as neurons. Interestingly, the change of gene regulation in neighbouring cells depends on microglia being present in the brain; when the researchers repeated the experiments using mice without microglia, the other brain cells did not react to the maternal immune response.

Although most viral infections are often short-lived, the scientists found that the changes that the maternal immune system causes in embryonic brain cells persist well after the immune reaction has subsided. “Based on previous studies demonstrating that microglia exposed to early infections respond differently to stimuli in adulthood, we hypothesized that the maternal immune response could induce changes in microglial gene regulation that persist postnatally,” said Dr. Bridget Ostrem, co-author of the study.

This research enhances our understanding of the cellular basis of neurodevelopmental disorders in humans. “Our results suggest a potential role for microglia as therapeutic targets in the setting of maternal infections,” said Ostrem, although there is still more work to be done. Harvard researcher Dr. Nuria Domínguez-Iturza added, “next, it will be crucial to determine the long-term behavioral implications of the changes we observed in this study.”

END

Mimicking infection in pregnant mice provokes persistent changes in juvenile brains

Cells responsible have now been identified

2024-05-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New study highlights significant increases in cannabis use in United States

2024-05-22

Many countries around the world are considering revising cannabis policies. A new study by a researcher at Carnegie Mellon University assessed cannabis use in the United States between 1979 and 2022, finding that a growing share of cannabis consumers report daily or near-daily use and that their numbers now exceed those of daily and near-daily alcohol drinkers. The study concludes that long-term trends in cannabis use parallel corresponding changes in policy over the same period. The study appears in Addiction.

“The data come from survey self-reports, but the enormous changes in ...

Bérénice Benayoun (USC) receives Rising Star Award in Aging Research

2024-05-22

New York, NY – The American Federation for Aging Research (AFAR), a national non-profit organization whose mission is to support and advance healthy aging through biomedical research, is pleased to recognize the exemplary contributions of Bérénice Benayoun, PhD, to the field of aging research through the 2024 Vincent Cristofalo Rising Star Award in Aging Research.

This award is named in honor of the late Dr. Cristofalo, who dedicated his career to aging research and encouraged young scientists to investigate important issues in the biology of aging. Established in 2008, the award ...

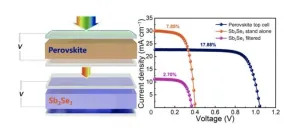

Team fabricates tandem solar cell with power conversion efficiency greater than 20 percent

2024-05-22

A research team has demonstrated for the first time a proof-of-concept tandem solar cell using antimony selenide as the bottom cell material and a wide-bandgap organic–inorganic hybrid perovskite material as the top cell material. The device achieved a power conversion efficiency of over 20 percent. This study shows that antimony selenide has great potential for bottom cell applications.

The research is published in the journal Energy Materials and Devices on March 4, 2024.

Photovoltaic technology, that harnesses sunlight and converts it into electricity, is popular because it provides a clean, renewable energy source. Scientists ...

Mitochondrial phosphate carrier plays an important role in virulence of Candida albicans

2024-05-22

This study is led by Professor Yan Wang (School of Pharmacy, Second Military Medical University (Naval Medical University), Shanghai, China). Her team found that the lack of MIR1 gene, which encodes mitochondrial phosphate carrier, can lead to severe virulence defects in Candida albicans.

In the Caenorhabditis elegans candidiasis model, the survival rate of the wild-type strain infected group dropped to about 20% at 120 h, while the survival rate of the mir1Δ/Δ-infected group remained about 90% at 120 h. Similar results were obtained in the murine model. None of the mice infected with mir1Δ/Δ mutant died during 21 days of ...

Enhanced plasticity of spontaneous coagulation cast oxide ceramic green bodies

2024-05-22

Spontaneous coagulation casting (SCC), a new type of colloidal forming process, has garnered significant attention since 2011 due to various advantages of a high bulk density and non-toxicity, as well as the ability to achieve dispersion and coagulation with very low additions (< 1 wt%) of copolymers of isobutylene and maleic anhydride (PIBM). Further research has revealed that the green bodies formed by this method are brittle, and the smaller the powder particle size used the more brittle the green bodies are. This paper reports ...

In vitro and circulation kinetic studies on π-π-stacked poly (ɛ-caprolactone)-based micelles loaded with olaparib

2024-05-22

Background and Aims

Olaparib is a selective poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor. However, its clinical application is hindered by low solubility and undesired pharmacokinetic profiles (e.g., relatively short circulation). Therefore, the present study aims to exploit polymeric micelles as a safe solubilizer and nanocarrier of olaparib, in order to improve its solubility and pharmacokinetics.

Methods

Poly (ε-caprolactone)-co-poly (benzyl 5-methyl-2-oxo-1,3-dioxane-5-carboxylate), i.e., benzyl-functionalized trimethylene carbonate)-b-poly (ethylene glycol) (P(CL-co-TMC-Bz)-PEG), was synthesized by ring-opening polymerization, ...

The effect of measurement depth and technical considerations in performing liver attenuation imaging

2024-05-22

Background and Aims

Clinical unmet need in managing nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a common liver disorder affecting 25–30% of American adults is to develop noninvasive and robust biomarkers.

Methods

We re-measured liver AC by placing a region of interest (ROI, 3 cm tall and 3 cm wide) at 4.5 cm, 6 cm, and 7.5 cm from the skin and a large ROI (6.0 cm tall and 7.3 cm wide) on pre-recorded ATI images from 117 participants screened for NAFLD. The difference in AC value at variable ROI depths was tested using one-way ANOVA (analysis of variance). Diagnostic ...

New study: Cuddled cows who work as therapy animals showed a strong preference for women compared to men

2024-05-22

A new study – published in the Human-Animal Interactions journal – reveals that cows who are cuddled as therapy animals showed a strong preference for interactions with women when compared to men.

In turn, the research, which opens a new era on whether some therapies may be initially stronger based upon gender and not procedure, highlighted that the women also reported greater attachment behaviours towards the steers.

Dr Katherine Compitus, Clinical Assistant Professor at New York University, and Dr Sonya Bierbower, Associate Professor at United States Military Academy West Point, conducted the research using the ...

Flexible film senses nearby movements — featured in blink-tracking glasses

2024-05-22

I’m not touching you! When another person’s finger hovers over your skin, you may get the sense that they’re touching you, feeling not necessarily contact, but their proximity. Similarly, researchers reporting in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces have designed a soft, flexible film that senses the presence of nearby objects without physically touching them. The study features the new sensor technology to detect eyelash proximity in blink-tracking glasses.

Noncontact sensors can identify or measure an object without directly touching it. Examples of these devices include ...

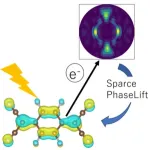

A simpler method for precise molecular orbital visualization

2024-05-22

Discoveries and progress in materials science often lay the foundation for technological breakthroughs that reshape many industrial and commercial fields, including medicine, consumer electronics, and energy generation, to name a few. Yet, the development of experimental techniques crucially underpins the exploration of new materials, paving the way for groundbreaking discoveries. These techniques allow scientists to delve into a material’s chemical and physical properties, unlocking insights essential for realizing their potential applications.

In a recent study ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

COSMOS trial results show daily multivitamin use may slow biological aging

Immune cells play key role in regulating eye pressure linked to glaucoma

National policy to remedy harms of race-based kidney function estimation associated with increased transplants for Black patients

Study finds teens spend nearly one-third of the school day on smartphones, with frequent checking linked to poorer attention

Team simulates a living cell that grows and divides

Study illuminates the experiences of people needing to seek abortion care out of state

Digital media use and child health and development

Seeking abortion care across state lines after the Dobbs decision

Smartphone use during school hours and association with cognitive control in youths ages 11 to 18

Maternal acetaminophen use and child neurodevelopment

Digital microsteps as scalable adjuncts for adults using GLP-1 receptor agonists

Researchers develop a biomimetic platform to enhance CAR T cell therapy against leukemia

Heart and metabolic risk factors more strongly linked to liver fibrosis in women than men, study finds

Governing with AI: a new AI implementation blueprint for policymakers

Recent pandemic viruses jumped to humans without prior adaptation, UC San Diego study finds

Exercise triggers memory-related brain 'ripples' in humans, researchers report

Increased risk of bullying in open-plan offices

Frequent scrolling affects perceptions of the work environment

Brain activity reveals how well we mentally size up others

Taiwanese and UK scientists identify FOXJ3 gene linked to drug-resistant focal epilepsy

Pregnancy complications impact women’s stress levels and cardiovascular risk long after delivery

Spring fatigue cannot be empirically proven

Do prostate cancer drugs interact with certain anticoagulants to increase bleeding and clotting risks?

Many patients want to talk about their faith. Neurologists often don't know how.

AI disclosure labels may do more harm than good

The ultra-high-energy neutrino may have begun its journey in blazars

Doubling of new prescriptions for ADHD medications among adults since start of COVID-19 pandemic

“Peculiar” ancient ancestor of the crocodile started life on four legs in adolescence before it began walking on two

AI can predict risk of serious heart disease from mammograms

New ultra-low-cost technique could slash the price of soft robotics

[Press-News.org] Mimicking infection in pregnant mice provokes persistent changes in juvenile brainsCells responsible have now been identified