(Press-News.org) As the planet has warmed, scientists have long been concerned about the potential for harmful greenhouse gasses to seep out of thawing Arctic permafrost. Recent estimates suggest that by 2100 the amount of carbon dioxide and methane released from these perpetually frozen lands could be on par with emissions from large industrial countries. However, new research led by a team of Colorado State University microbiome scientists suggests those estimates might be too low.

Microorganisms are responsible for the process that will generate greenhouse gasses from thawing northern peatlands, which contain about 50% of the world’s soil carbon. For now, many of the microbes in this environment are frozen and inactive. But as the land thaws the microbes will “wake up” and begin to churn through carbon in the ground. This natural process, known as microbial respiration, is what produces the carbon dioxide and methane emissions forecasted by climate modelers.

Currently, these models assume that this community of microorganisms — known as a microbiome — will break down some types of carbon but not others. But the CSU-led work published this week in the journal Nature Microbiology provides new insight into how these microbes will behave once activated. The research demonstrates that the soil microbes embedded in the permafrost will go after a class of compounds previously thought to be untouchable under certain conditions: polyphenols.

“There were these pools of carbon — say, donuts, pizza and chips — and we were comfortable with the idea that microbes were going to use this stuff,” said Bridget McGivern, a CSU postdoctoral researcher and the paper’s first author. “But then there was this other stuff, spicy food; we didn’t think the organisms liked spicy food. But what our work is showing is that actually there are organisms that are eating it, and so it’s not going to just stay as carbon, it’s going to be broken down.”

More carbon being broken down by microbial respiration will produce additional greenhouse gas emissions. But this new finding has other implications, too. Some scientists had previously theorized that adding polyphenols to the thawing Arctic permafrost could potentially “turn off” these microorganisms altogether, effectively trapping a massive cache of potentially problematic carbon in the ground. The concept is known as the enzyme latch theory.

That no longer appears to be a viable option, said Kelly Wrighton, associate professor in the College of Agricultural Sciences’ Department of Soil and Crop Sciences, whose lab led the work. “Not only did we think these microbes didn’t eat polyphenols,” Wrighton said, “we thought that if the polyphenols were there it was like they were toxic and would lock the microbes into inactivity.”

The soil microbiome has often been considered something of a black box due of its complexity. Wrighton hopes this new information about the role of polyphenols in permafrost helps shift that perception. “I’d like to move past these black box assumptions,” she said. “We can’t engineer solutions if we don’t understand the underlying wiring and plumbing of a system.”

Probing the permafrost in Sweden

Unlocking the relationship between soil microbes and polyphenols has been years in the making for McGivern, who began examining this topic while working on her doctoral degree in Wrighton’s lab in 2017.

McGivern started with a simple question. Scientists presumed that without oxygen, soil microbes could not break down polyphenols. Gut microbes, however, don’t need oxygen to churn up the compound — that’s how humans extract healthy antioxidant benefits from polyphenol-rich substances such as chocolate and red wine. McGivern wondered why the process would be different in soils, a question that is particularly relevant to permafrost or waterlogged lands that contain little or no oxygen.

“The motivation for a lot of my Ph.D. was how could these two things exist?” McGivern said. “Organisms in our gut can breakdown polyphenols but organisms in the soil can’t? The reality was that nobody in soils had really ever looked at it.”

McGivern and Wrighton successfully tested the theory in a lab experiment and published a proof of concept study in 2021. The next step was testing it in the field. The team gained access to core samples from a research site in northern Sweden, a place that scientists have used for years to examine questions related to permafrost and the soil microbiome.

But before McGivern could look for evidence of polyphenol degradation in the core samples, she first had to create a database of gene sequences that corresponded to polyphenol metabolism. McGivern mined thousands of pages of existing scientific literature, cataloging the enzymes in cattle, the human gut, and some soils that were known to be responsible for the process. Once she built the database, McGivern compared the results to the gene sequences expressed by the microbes in the core samples. Sure enough, she said, polyphenol metabolism was happening.

“What we found was that genes across 58 different polyphenol pathways were expressed,” McGivern said. “So, we’re saying not only can the microorganisms potentially do it, but they actually are, in the field, expressing the genes for this metabolism.”

Still, more work is needed, McGivern said. They don’t know what might constrain the process or the rates at which the metabolism is happening — both important factors for eventually quantifying the amount of additional greenhouse gas emissions that could be released from permafrost.

“The whole point of this is to build a better predictive understanding so that we have a framework we can actually manipulate,” Wrighton said. “The climate crisis we’re facing is so fast. But can we model it? Can we predict it? The only way we’re going to get there is to actually understand how something works.”

END

New research shows soil microorganisms could produce additional greenhouse gas emissions from thawing permafrost

2024-05-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Introducing peanut in infancy prevents peanut allergy into adolescence

2024-05-28

Feeding children peanut products regularly from infancy to age 5 years reduced the rate of peanut allergy in adolescence by 71%, even when the children ate or avoided peanut products as desired for many years. These new findings, from a study sponsored and co-funded by the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), provide conclusive evidence that achieving long-term prevention of peanut allergy is possible through early allergen consumption. The results were published today in the journal NEJM Evidence.

“Today’s findings should reinforce parents’ and caregivers’ ...

Light-activated drugs targeting adenosine A2A receptors in the brain that induce sleep

2024-05-28

Tsukuba, Japan—The nucleus accumbens plays a pivotal role in motivational behavior and sleep regulation, modulated by adenosine A2A receptors (A2AR). Hence, selective A2AR regulation within this brain region could control sleep and motivation. However, A2ARs are distributed across various organs, including the heart, posing challenges for precise brain-specific modulation without genetic interventions.

A research team led by Professor Michael Lazarus and Associate Professor Tsuyoshi Saitoh (TRiSTAR Fellow) from the Institute of Medicine and the International Institute for Integrative Sleep Medicine (WPI-IIIS) at the University ...

SwRI data fusion tool targets urban heat islands in San Antonio

2024-05-28

SAN ANTONIO — May 28, 2024 —Southwest Research Institute has created a comprehensive data analysis tool to help metropolitan areas curb urban heat islands (UHIs) and pursue mitigation methods for especially vulnerable populations. This internally funded project was a collaboration with the City of San Antonio.

UHIs occur when dense concentrations of pavement and buildings absorb heat and raise surrounding temperatures. Without green spaces to provide a cooling effect, UHI temperatures can exceed other areas by as much as 20 degrees Fahrenheit, which could be dangerous to residents during summer.

“Tackling UHIs goes ...

Does the requirement to offer retirement plans help workers save for retirement?

2024-05-28

A study published in Contemporary Economic Policy reveals significant benefits gained from the first implementation of the state-run retirement savings program in Oregon, known as OregonSaves, in 2017.

OregonSaves is available to Oregon workers whose employers do not offer a workplace retirement plan, self-employed individuals, and others. Businesses that do not offer retirement plans are required to automatically enroll employees, but workers can opt out at any time.

The analysis found that the program substantially boosted retirement savings among previously ...

Apple versus donut: How the shape of a tokamak impacts the limits of the edge of the plasma

2024-05-28

Harnessing energy from plasma requires a precise understanding of its behavior during fusion to keep it hot, dense and stable. A new theoretical model about a plasma’s edge, which can become unstable and bulge, brings the prospect of commercial fusion power closer to reality.

“The model refines the thinking on stabilizing the edge of the plasma for different tokamak shapes,” said Jason Parisi, a staff research physicist at PPPL. Parisi is the lead author of three articles describing the model that were published in the journals Nuclear Fusion and Physics of Plasma. The primary paper focuses on a part of the plasma called ...

Valentin Fuster, MD, PhD, receives prestigious award from World Heart Federation

2024-05-28

The World Heart Federation (WHF) is honoring Valentin Fuster, MD, PhD, President of Mount Sinai Heart and Physician-in-Chief of The Mount Sinai Hospital, with its Lifetime Achievement Award for 2024. This top honor recognizes his remarkable contributions to the WHF mission, and to the entire cardiovascular disease community for his dedication to combating this disease worldwide.

The WHF will present Dr. Fuster with this award on Saturday, May 25, during the World Heart Summit in Geneva, Switzerland.

“I am proud of this award, particularly because it represents Mount Sinai’s worldwide scientific contributions and dedication to advancements in the cardiovascular ...

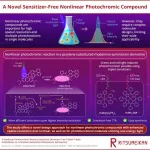

Nonlinear photochromic properties in a perylene-substituted rhodamine spirolactam

2024-05-28

Photochromic compounds, which change their color when exposed to light, have been widely used as photoswitches to control different properties of materials. Nonlinear photochromic compounds, characterized by a nonlinear response to the intensity of incident light, have attracted special attention among researchers as the nonlinearity leads to enhanced contrast and improved spatial resolution in photochromic reactions. It also allows for multiple photochromic properties in a single molecule with a single light source. These qualities have made them valuable in nonlinear optical and holographic elements, super-resolution microscopy, and biomedical applications.

The simplest ...

Binge-eating disorder not as transient as previously thought

2024-05-28

BELMONT, Mass. (May 28, 2024) Binge-eating disorder is the most prevalent eating disorder in the United States, but previous studies have presented conflicting views of the disorder’s duration and the likelihood of relapse. A new five-year study led by investigators from McLean Hospital, a member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system, showed that 61 percent and 45 percent of individuals still experienced binge-eating disorder 2.5 and 5 years after their initial diagnoses, respectively. These results contradict previous ...

Pharmacists prove effective, less costly care option for minor illnesses

2024-05-28

SPOKANE, Wash. – Greater use of pharmacists to treat minor illnesses could potentially save millions of dollars in health care costs, according to new research led by Washington State University. The findings also indicate a way to improve healthcare access by expanding availability of pharmacists’ clinical services including prescribing medications, amid an ongoing shortage of primary care providers.

The study found that care for a range of minor health issues – including urinary tract infections, shingles, animal bites and headaches – costs an average of about $278 less when treated in pharmacies compared to patients with similar ...

Inexpensive microplastic monitoring through porous materials and machine learning

2024-05-28

Optical analysis and machine learning techniques can now readily detect microplastics in marine and freshwater environments using inexpensive porous metal substrates. Details of the method, developed by researchers at Nagoya University with collaborators at the National Institute for Materials Sciences in Japan and others, are published in the journal Nature Communications.

Detecting and identifying microplastics in water samples is essential for environmental monitoring but is challenging due in part to the structural similarity of microplastics with natural organic compounds derived from biofilms, algae, and decaying organic matter. Existing detection methods ...