(Press-News.org) (Santa Barbara, Calif.) — A great armada entered the North Atlantic, launched from the cold shores of North America. But rather than ships off to war, this force was a fleet of icebergs. And the havoc it wrought was to the ocean current itself.

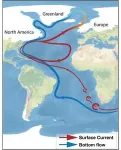

This scene describes a Heinrich Event, or a period of rapid iceberg discharge from the Laurentide Ice Sheet during the last glacial maximum. These episodes greatly weakened the system of ocean currents that circulates water within the Atlantic Ocean. The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC for short, brings warm surface water north and cold deep water south. This oceanic conveyor belt is a major component of the global climate system, influencing marine ecosystems, weather patterns and temperatures.

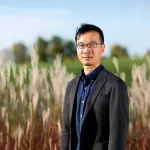

It’s also regarded as a potential tipping element of the Earth's climate, meaning that a tiny perturbation could push the system to a point of no return. “That’s why a lot of people are worried about a potential collapse of the AMOC,” said Yuxin Zhou, a postdoctoral researcher in UC Santa Barbara’s Department of Earth Science. A weakened AMOC would have a global impact, dropping temperatures in the northern hemisphere and raising them in the south. We’d see dramatic cooling in western Europe and eastern North America, and changes in the tropical rain belt that impact the Amazon and central Africa.

Zhou compared the rate of icebergs coming from the Greenland Ice Sheet to ice flux during Heinrich Events, the last time the AMOC collapsed. He found that as Greenland’s ice sheet retreats inland, its iceberg calving likely will not persist long enough to completely derail the Atlantic circulation. That said, increased freshwater runoff and continued global warming remain threats to the circulation’s stability. The results appear in the journal Science.

“I think that sometimes people are in such despair about the future of the climate that they just give up,” Zhou said. “This study is saying that there is still hope, and we should act with that in mind.”

The North Atlantic is the lynchpin of the AMOC. This is where surface water chills and sinks to the deep ocean, driving this marine conveyor belt, which is a component of the global current system. Adding cold freshwater to the North Atlantic can disrupt this process, a frightening prospect for human society.

Scientists have a number of ways to predict how the AMOC will evolve in the future, including modern observations, statistical analyses and computational models. But the ocean is vast and complex, making it difficult to capture many of its nuances in studies.

Zhou went back in history to study the most recent period when the AMOC was severely weakened — from 68,000 to 16,000 years ago, during the last glacial period. During cooler periods there is more water locked up in ice sheets, creating a reservoir for quickly flushing the ocean with freshwater in the form of icebergs or runoff. Scientists call these episodes Heinrich Events when they came from the Laurentide Ice Sheet. “Today it does not exist. But it used to cover northern North America and was kilometers thick in New York City,” Zhou said.

Comparing these Heinrich Events to current melting in Greenland enabled Zhou to predict how current trends might change the AMOC in the future. Icebergs bring larger sediment out to sea than water or wind, a signature that geologist Hartmut Heinrich noticed in seafloor cores in the North Atlantic. To estimate how much ice each Heinrich Event released, Yuxin analyzed the amount of thorium-230 found in these sediments. This radioactive element is formed from the decay of naturally occurring uranium in seawater. Unlike uranium, thorium doesn’t dissolve well in water, so it precipitates out on particles in the water column. Because thorium-230 is produced at a steady rate, more sediment flux dilutes its concentration. Working in reverse: Less thorium means more sediment raining down, carried by more icebergs.

While this technique has been used before, Zhou is the first to compare the melting rate of icebergs during Heinrich Events to current trends and projections for Greenland’s ice sheet. Zhou discovered that Greenland’s predicted ice outflow is on par with a mid-range Heinrich Event. And what are the effects of a mid-range Heinrich Event?

“Dramatic,” Zhou replied. “It can be bad.”

“This is surprising, and people should be worried. But — and this is a big ‘but’ — during Heinrich Events, the AMOC was already moderately weakened before all the icebergs came in,” he said. “In contrast, the circulation is very vigorous right now.” This difference in initial state is cause for some relief.

Heinrich Events also lasted for tens to hundreds of years. In contrast, the industrial revolution only began around the late 18th century, with carbon emissions ramping up much later. “It is possible that we simply haven’t screwed up badly enough for long enough for it to really mess up the AMOC,” Zhou remarked.

There’s another nuance to the story. Not all melting has the same effect on the Atlantic circulation. Freshwater released as icebergs has a much larger impact on the AMOC than runoff, which is released after melting on land. Icebergs can cool the surrounding seawater, causing it to freeze into sea ice. Ironically, this ice layer acts as a blanket, keeping the ocean surface warm and preventing it from plunging down to the depths and driving the Atlantic circulation. What’s more, icebergs travel much farther out to sea than runoff, delivering freshwater to the regions where this deepwater formation occurs.

Scientists on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predict that the AMOC will weaken moderately over the 21st century, a trend similar to the effects of a Heinrich Event. However, Greenland’s ice discharge is projected to dwindle by that time as its ice sheet melts. This will cause its glaciers to recede inland, meaning they melt on land and release freshwater runoff rather than icebergs.

“This presents a tug-o-war between these two factors: the more disruptive but decreasing ice discharge and the less effective but accelerating runoff,” Zhou explained. “It’s going to be a competition, and the interplay between the two will determine the future of the AMOC.”

Zhou hopes to study the factors that caused Heinrich Events in the future. Some research suggests that each episode was preceded by ice discharge in the Pacific Ocean from the smaller Cordilleran Ice Sheet. Although this ice sheet hasn’t left any remnants, Zhou believes studying these Siku Events, as the latter are known, could provide more insight on global ocean circulation.

He’s also interested in the sediments around Antarctica. While Greenland’s location causes it to dominate the AMOC, the southern ice sheet is much larger, meaning it could have a greater influence on global sea level and salinity. Further, the West Antarctic Ice Sheet is marine based, making it more susceptible to a feedback loop that could induce runaway melting. Zhou believes that applying the methodologies in this study to the Antarctic ice sheets could provide a better understanding of their future evolution and impacts.

“We have a lot of anxiety about how fast climate change is happening and how dramatic the changes could be,” Zhou said. “But this is a piece of good climate news that hopefully will dissuade people from climate doomism, and give people hope, because we do need hope to fight the climate crisis.”

END

Historic iceberg surges offer insights on modern climate change

The future of the Atlantic circulation will be determined by a tug-o-war between Greenland’s decreasing ice flux and its increasing freshwater runoff

2024-05-30

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Reexamining misinformation: How unflagged, factual content drives vaccine hesitancy

2024-05-30

What threatens public health more, a deliberately false Facebook post about tracking microchips in the COVID-19 vaccine that is flagged as misinformation, or an unflagged, factual article about the rare case of a young, healthy person who died after receiving the vaccine?

According to Duncan J. Watts, Stevens University Professor in Computer and Information Science at Penn Engineering and Director of the Computational Social Science (CSS) Lab, along with David G. Rand, Erwin H. Schell Professor at MIT Sloan School of Management, and Jennifer Allen, 2024 MIT Sloan School of Management Ph.D. graduate ...

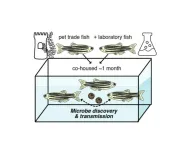

Novel virus identified in zebrafish from the pet trade causes disease in laboratory fish

2024-05-30

Zebrafish in the pet trade are asymptomatic carriers of previously undescribed microbes, including a novel virus that causes hemorrhaging in infected laboratory fish, Marlen Rice from the University of Utah, US, and colleagues report in the open-access journal PLOS Biology, publishing May 23rd.

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) are a common laboratory research animal, and they are also widely available as pets. In research laboratories, they are kept in specialized aquaculture facilities to prevent infectious disease, but zebrafish are occasionally ...

Cuckoos evolve to look like their hosts - and form new species in the process

2024-05-30

The theory of coevolution says that when closely interacting species drive evolutionary changes in each other this can lead to speciation - the evolution of new species. But until now, real-world evidence for this has been scarce.

Now a team of researchers has found evidence that coevolution is linked to speciation by studying the evolutionary arms race between cuckoos and the host birds they exploit.

Bronze-cuckoos lay their eggs in the nests of small songbirds. Soon after the cuckoo chick hatches, it pushes the host’s eggs out of the nest. The host not only loses all its own eggs, but spends several ...

Cause of heart failure may differ for women and men

2024-05-30

A new study from the UC Davis School of Medicine found striking differences at the cellular level between male and female mice with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

The findings could determine how HFpEF is treated in women compared to men.

With HFpEF, the heart muscle contracts normally but the heart is unable to fully relax and refill properly between beats. This condition is known as diastolic dysfunction. It can occur if the heart is too stiff or if the contraction process doesn’t shut off quickly enough between ...

Tiny worm helps uncover long-lasting prenatal effects from amphetamines

2024-05-30

Amphetamine is a psychostimulant that has been used to treat a variety of brain dysfunctions. However, it is a highly abused drug. In fact, amphetamine and amphetamine-derived compounds such as methamphetamine (Meth) are among the most abused psychostimulants in the world.

The neurological effects caused by acute or chronic use of amphetamine have been broadly investigated and several studies have shown that proteins involved in the synthesis, storage, release and reuptake of dopamine (DA), a neurotransmitter that plays a role as in ...

Banners backfire: Misinformation impact on search results

2024-05-30

ITHACA, N.Y. – Cornell University researchers have found in a public health emergency, most people pick out and click on accurate information during internet searches.

Though higher-ranked results are clicked more often, they are not more trusted. And the presence of misinformation does not damage trust in accurate results that appear on the same page. However, banners at the top of the search results page warning about misinformation decrease trust in accurate information, according to the research published in Scientific Reports.

The relationship between ...

UC3M is a shareholder of five of its researchers’ new spin-offs

2024-05-30

The Universidad Carlos III de Madrid (UC3M) has become a shareholder of five new companies recently set up and promoted by different researchers: Applied Innovative Methods, Hiili, Persei Space, Seevia Technologies and 60Nd.

UC3M participates in the share capital of its spin-offs in order to contribute to their business development. This minority and temporary shareholding is articulated in accordance with the regulations for the creation of knowledge-based university companies.

AI Methods, S.L., led by Manuel Soler ...

New method makes hydrogen from solar power and agricultural waste

2024-05-30

University of Illinois Chicago engineers have helped design a new method to make hydrogen gas from water using only solar power and agricultural waste, such as manure or husks. The method reduces the energy needed to extract hydrogen from water by 600%, creating new opportunities for sustainable, climate-friendly chemical production.

Hydrogen-based fuels are one of the most promising sources of clean energy. But producing pure hydrogen gas is an energy-intensive process that often requires coal or natural gas and large amounts of electricity.

In a paper for Cell Reports Physical Science, a multi-institutional ...

Credibility makes or breaks the price: political commitment in long-term climate policy key for effective EU emissions trading system

2024-05-30

“The price on emitting carbon that is harmful to the climate has risen sharply in the past; basically, it roughly increased tenfold over the last five years and two policy reforms. Our analysis implies that besides directly changing the ETS rules, the reforms also increased the long-term credibility of the EU ETS and thereby made firms more farsighted, aligning their market behaviour with long-term climate targets,” explains Joanna Sitarz, PIK scientist and first author of the study published in Nature Energy. “In ...

Slow-growth diet before breeding offered better long-range health in pigs

2024-05-30

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. — Borrowing a page from the dairy industry, researchers with the Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station found that a slow-growth diet meant more piglets and healthier and longer-lived momma pigs.

Slowing weight gain for female pigs before breeding showed improvements in performance throughout four breeding cycles, according to Charles Maxwell, professor of animal science for the experiment station, the research arm of the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture.

“Scientists have done a wonderful job of increasing litter size and milk production so that our sow lines are essentially ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Nanoplastics can interact with Salmonella to affect food safety, study shows

Eric Moore, M.D., elected to Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees

NYU named “research powerhouse” in new analysis

New polymer materials may offer breakthrough solution for hard-to-remove PFAS in water

Biochar can either curb or boost greenhouse gas emissions depending on soil conditions, new study finds

Nanobiochar emerges as a next generation solution for cleaner water, healthier soils, and resilient ecosystems

Study finds more parents saying ‘No’ to vitamin K, putting babies’ brains at risk

Scientists develop new gut health measure that tracks disease

Rice gene discovery could cut fertiliser use while protecting yields

Jumping ‘DNA parasites’ linked to early stages of tumour formation

Ultra-sensitive CAR T cells provide potential strategy to treat solid tumors

Early Neanderthal-Human interbreeding was strongly sex biased

North American bird declines are widespread and accelerating in agricultural hotspots

Researchers recommend strategies for improved genetic privacy legislation

How birds achieve sweet success

More sensitive cell therapy may be a HIT against solid cancers

Scientists map how aging reshapes cells across the entire mammalian body

Hotspots of accelerated bird decline linked to agricultural activity

How ancient attraction shaped the human genome

NJIT faculty named Senior Members of the National Academy of Inventors

App aids substance use recovery in vulnerable populations

College students nationwide received lifesaving education on sudden cardiac death

Oak Ridge National Laboratory launches the Next-Generation Data Centers Institute

Improved short-term sea level change predictions with better AI training

UAlbany researchers develop new laser technique to test mRNA-based therapeutics

New water-treatment system removes nitrogen, phosphorus from farm tile drainage

Major Canadian study finds strong link between cannabis, anxiety and depression

New discovery of younger Ediacaran biota

Lymphovenous bypass: Potential surgical treatment for Alzheimer's disease?

When safety starts with a text message

[Press-News.org] Historic iceberg surges offer insights on modern climate changeThe future of the Atlantic circulation will be determined by a tug-o-war between Greenland’s decreasing ice flux and its increasing freshwater runoff