Human cervix modeled in microfluidic organ chip fills key women's health gap

Engineered cervix with in vivo-like mucus production, hormone sensitivity, and associated microbiome creates novel testbed for bacterial vaginosis therapeutics and other treatments

By Benjamin Boettner

(BOSTON) — Bacterial Vaginosis (BV) has been identified as one of the many unmet needs in women's health and affects more than 25% of reproductive-aged women. It is caused by pathogenic bacteria that push the healthy microbiomes in the female vagina and cervix – the small gatekeeper canal that connects the uteruns and vagina – into a state of imbalance known as dysbiosis. This dysbiosis then triggers inflammation that not only causes severe discomfort, but can also can result in a host of downstream complications, including an increased risk for infection with HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases, higher rates of spontaneous abortion and pre-term birth, as well as pelvic and endometrial inflammatory diseases.

Thus far, the only treatments for BV are antibiotics, which often fail to kill the invading bacteria in the infected vagina and cervix. Antibiotic therapies also don’t prevent the recurrence of this condition in more than 60% of women. Although BV was first described more than a century ago, the pathogenic events following the initial infection remain very poorly understood, which contributes to the dearth of more effective BV treatments.

Now, filling an important gap, a collaborative team of researchers at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University and University of California Davis, led by Wyss Founding Director Donald Ingber, M.D., Ph.D., developed a microfluidic human in vitro model of the complex cervix tissue, a human Cervix-on-a-Chip (Cervix Chip), that overcomes major limitations of existing animal models and static in vitro models. With unprecedented fidelity and detail, the Cervix Chip replicates the complex interactions between the cervical epithelial cells, the protective mucus layer they produce, and the cervical microbiome in its healthy state as well as when it is under attack from BV-causing bacteria. Their findings are published in Nature Communications.

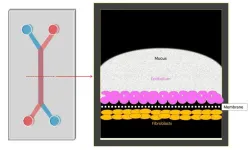

The researchers created an Organ Chip model of the cervical wall by growing human cervical epithelial cells in one of two parallel channels running through a microfluidic device the size of a USB memory stick and growing cervical fibroblast cells in the adjacent channel. The channels are separated by a porous membrane which allows the two cell types to communicate similarly as in a woman’s body. Importantly, the team was able to reconstitute the two major sections of the cervical wall by identifying alternative flow-conditions used to perfuse the epithelial channel with medium, which produced region-specific mechanical cues.

Their Cervix Chip technology enabled the team to also replicate the mucus production of the cervix, and how mucus features change under the influence of sex hormones, as well as healthy and pathogenic microbial communities. “Our engineered cervix model and the breadth and depth of analysis it allows sets a new standard in research that is well in line with existing clinical observations, while offering first new insights into cervix functionality and vulnerability,” said first author Zohreh Izadifar, Ph.D., who spearheaded the project as a Postdoctoral Fellow on Ingber’s team and now is a Research Faculty member at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School (HMS).

The study’s accomplishments are an important milestone toward the envisioned goals of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which funded the project. The foundation had identified highly prevalent BV in African women as an area of high priority, as it dramatically increases the risk of pre-term births and HIV infection on the continent. With the end goal of finding urgently needed treatments against BV, the foundation formed a research consortium that includes Ingber as well as co-senior author Carlito Lebrilla, Ph.D. at University of California Davis.

“In this study, we leveraged critical findings that we had made in a previously developed Vagina Chip to create a platform that now enables researchers to find answers to additional long-standing questions in womens’ health,” said Ingber. “The Cervix Chip can be used alongside the Vagina Chip to evaluate the efficacy of potential new treatments in the form of live biotherapeutic products that other members of our Gates Foundation-funded consortium are developing for treatment of BV. We also hope to use the chip to identify new treatments for other infectious disease of the female reproductive tract.” Ingber is also the Judah Folkman Professor of Vascular Biology at HMS and Boston Children’s Hospital, and the Hansjörg Wyss Professor of Bioinspired Engineering at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

The female cervix at high resolution

The cervical canal consists of two distinct sections: the lower cervical canal, known as the ectocervix, leading into the vagina, and the upper cervical canal, known as the endocervix, which connects to the uterus. The endocervix produces most mucus in the lower female reproductive tract, periodically discharging it before it continues its journey in a more even flow through the ectocervix and vagina, both of which produce lesser amounts of additional mucus. Mirroring this physiology, the team found that exposing the Cervix Chip only periodically to fluid flow causes it to generate a thin monolayered epithelium typical of the endocervix, while exposing it continuously to fluid flow results in the thick ectocervix-like multi-layered epithelium. On-chip, both cervical epithelia displayed their typical gene expression patterns.

Mucus is a complex substance that consists of mucin proteins that are decorated with highly branched tress of various sugar molecules. The team’s collaborator Lebrilla is an expert in analytical chemistry and sugar biology, and his team undertook an in-depth “glycomics” analysis of the sugars making up the mucus produced in the Cervix Chip under different conditions. This joint effort enabled the researchers to confirm that the sugar structures of the mucus closely resembled those found in samples obtained from women. Importantly, the modeled cervix responded to sex hormone concentrations typical of the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle by increasing the thickness, water content, and altering the sugar arrangements of the produced mucus when compared to luteal hormone conditions. It also produced a stronger inflammatory response and slightly reduced its protective barrier functions in the follicular phase. “All of these findings closely reflect cervix physiology described from clinical observations,” said Izadifar.

Studying BV in the Cervix Chip

In the development of BV, aggressive pathogenic bacteria migrate from the vagina through the cervical canal up to the cervix, which, with its mucus production and immune-modulating abilities, normally functions as a gatekeeper against infections. When they take over the local beneficial bacterial communities, dysbiosis emerges. The pathological outcomes of this invasion are closely associated with alterations in the protective mucus layer, and the pathogenic bacteria gaining access to the underlying epithelia.

To mimic healthy and pathological microbial conditions in the Cervix Chip, the researchers first populated it with Lactobacillus crispatus bacteria, which dominate healthy cervical microbiomes. The L. crispatus bacteria induced the mucus layer to thicken and improve its quality, while leaving the underlying epithelium fully intact during three days of co-culture. Moreover, their presence induced the expression of proteins in cervical epithelial cells that are involved in their normal differentiation and protection against pathogens.

When they instead populated the Cervix Chip with Gardnerella vaginalis bacteria, which cause dysbiosis, the epithelium’s barrier functions became severely compromised. In addition, the expression of proteins associated with pathogenic processes, including inflammation, was significantly elevated. “Interestingly, we identified specific mucus structural and sugar modifications that could help explain the deterioration of the mucus’s quality related to BV, and indirectly could have an impact on downstream pathological processes,” said Izadifar. “In the future, our bottom-up approach to reconstituting the female cervix and its in vivo-like responsiveness will allow us to comprehensively investigate the relevance of the cervix’s distinct tissue and microbial components in diverse pathologies.”

Additional authors on the study are Justin Cotton, Siyu Chen, Viktor Horvath, Anna Stejskalova, Aakanksha Gulati, Nina LoGrande, Bogdan Budnik, Sanjid Shahriar, Erin Doherty, Yixuan Xie, Tania To, Sarah Gilpin, Adama Sesay, and Girja Goyal. In addition to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the study was supported by Wyss Institute and a fellowship by Canada’s Natural Science and Engineering Research Council to Izadifar

PRESS CONTACTS

Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University

Benjamin Boettner, benjamin.boettner@wyss.harvard.edu

###

The Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University (www.wyss.harvard.edu) is a research and development engine for disruptive innovation powered by biologically-inspired engineering with visionary people at its heart. Our mission is to transform healthcare and the environment by developing ground-breaking technologies that emulate the way Nature builds and accelerate their translation into commercial products through formation of startups and corporate partnerships to bring about positive near-term impact in the world. We accomplish this by breaking down the traditional silos of academia and barriers with industry, enabling our world-leading faculty to collaborate creatively across our focus areas of diagnostics, therapeutics, medtech, and sustainability. Our consortium partners encompass the leading academic institutions and hospitals in the Boston area and throughout the world, including Harvard’s Schools of Medicine, Engineering, Arts & Sciences and Design, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston Children’s Hospital, Dana–Farber Cancer Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, Boston University, Tufts University, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, University of Zürich, and Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

END