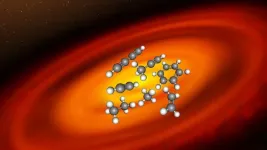

(Press-News.org) Planets form in disks of gas and dust, orbiting young stars. The MIRI Mid-INfrared Disk Survey (MINDS), led by Thomas Henning from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA) in Heidelberg, Germany, aims to establish a representative disk sample. By exploring their chemistry and physical properties with MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument) on board the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), the collaboration links those disks to the properties of planets potentially forming there. In a new study, a team of researchers explored the vicinity of a very low-mass star of 0.11 solar masses (known as ISO-ChaI 147), whose results appear in the journal Science.

JWST opens a new window to the chemistry of planet-forming disks

“These observations are not possible from Earth because the relevant gas emissions are absorbed by its atmosphere,” explained lead author Aditya Arabhavi of the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. “Previously, we could only identify acetylene (C2H2) emission from this object. However, JWST’s higher sensitivity and the spectral resolution of its instruments allowed us to detect weak emission from less abundant molecules.”

The MINDS collaboration found gas at temperatures around 300 Kelvin (ca. 30 degrees Celsius), strongly enriched with carbon-bearing molecules but lacking oxygen-rich species. “This is profoundly different from the composition we see in disks around solar-type stars, where oxygen-bearing molecules such as water and carbon dioxide dominate,” added team member Inga Kamp, University of Groningen.

One striking example of an oxygen-rich disk is the one of PDS 70, where the MINDS program recently found large amounts of water vapour. Considering earlier observations, astronomers deduce that disks around very low-mass stars evolve differently than those around more massive stars such as the Sun, with potential implications for finding rocky planets with Earth-like characteristics there. Since the environments in such disks set the conditions in which new planets form, any such planet may be rocky but quite unlike Earth in other aspects.

What does it mean for rocky planets orbiting very low-mass stars?

The amount of material and its distribution across those disks limits the number and sizes of planets the disk can supply with the necessary material. Consequently, observations indicate that rocky planets with sizes similar to Earth form more efficiently than Jupiter-like gas giants in the disks around very low-mass stars, the most common stars in the Universe. As a result, very low-mass stars host the majority of terrestrial planets by far.

“Many primary atmospheres of those planets will probably be dominated by hydrocarbon compounds and not so much by oxygen-rich gases such as water and carbon dioxide,” Thomas Henning pointed out. “We showed in an earlier study that the transport of carbon-rich gas into the zone where terrestrial planets usually form happens faster and is more efficient in those disks than the ones of more massive stars.”

Although it seems clear that disks around very low-mass stars contain more carbon than oxygen, the mechanism for this imbalance is still unknown. The disk composition is the result of either carbon enrichment or the reduction of oxygen. If the carbon is enriched, the cause is probably solid particles in the disk, whose carbon is vaporised and released into the gaseous component of the disk. The dust grains, stripped of their original carbon, eventually form rocky planetary bodies. Those planets would be carbon-poor, as is Earth. Still, carbon-based chemistry would likely dominate at least their primary atmospheres provided by disk gas. Therefore, very low-mass stars may not offer the best environments for finding planets akin to Earth.

JWST discovers a wealth of organic molecules

To identify the disk gases, the team used MIRI’s spectrograph to decompose the infrared radiation received from the disk into signatures of small wavelength ranges – similar to sunlight being split into a rainbow. This way, the team isolated a wealth of individual signatures attributed to various molecules.

As a result, the observed disk contains the richest hydrocarbon chemistry seen to date in a protoplanetary disk, consisting of 13 carbon-bearing molecules up to benzene (C6H6). They include the first extrasolar ethane (C2H6) detection, the largest fully-saturated hydrocarbon detected outside the Solar System. The team also successfully detected ethylene (C2H4), propyne (C3H4), and the methyl radical CH3 for the first time in a protoplanetary disk. In contrast, the data contained no hint of water or carbon monoxide in the disk.

Sharpening the view of disks around very low-mass stars

Next, the science team intends to expand their study to a larger sample of such disks around very low-mass stars to develop their understanding of how common such exotic carbon-rich terrestrial planet-forming regions are. “Expanding our study will also allow us to understand better how these molecules can form,” Thomas Henning explained. “Several features in the data are also still unidentified, warranting additional spectroscopy to interpret our observations fully.”

Background information

The study was funded in the framework of the ERC Advanced Grant “Origins – From Planet-Forming Disks to Giant Planets” (Grant ID: 832428, PI: Thomas Henning, DOI: 10.3030/832428).

The MPIA scientists involved in this study are Thomas Henning, Matthias Samland, Giulia Perotti, Jeroen Bouwman, Silvia Scheithauer, Riccardo Franceschi, Jürgen Schreiber, and Kamber Schwartz.

Other researchers include Aditya Arabhavi (University of Groningen, the Netherlands [Groningen]), Inga Kamp (Groningen), Ewine van Dishoeck (Leiden University, the Netherlands and Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, Garching, Germany), Valentin Christiaens (University of Liege, Belgium), and Agnes Perrin (Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique/IPSL CNRS, Palaiseau, France).

The MIRI consortium consists of the ESA member states Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. The national science organisations fund the consortium’s work – in Germany, the Max Planck Society (MPG) and the German Aerospace Center (DLR). The participating German institutions are the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, the University of Cologne, and Hensoldt AG in Oberkochen, formerly Carl Zeiss Optronics.

JWST is the world’s premier space science observatory. It is an international program led by NASA jointly with its partners, ESA (European Space Agency) and CSA (Canadian Space Agency).

END

Planet-forming disks around very low-mass stars are different

JWST discovers a large variety of carbon-rich gases that serve as ingredients for future planets around a very low-mass star

2024-06-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

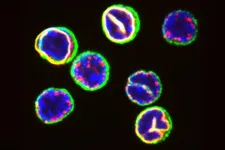

Researchers identify key differences in inner workings of immune cells

2024-06-06

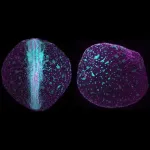

From the outside, most T cells look the same: small and spherical. Now, a team of researchers led by Berend Snijder from the Institute of Molecular Systems Biology at ETH Zurich has taken a closer look inside these cells using advanced techniques. Their findings show that the subcellular spatial organisation of cytotoxic T cells – which Snijder refers to as their cellular architecture – has a major influence on their fate.

Characteristics that determine a cell’s fate

When cells with nuclear invaginations encounter a pathogen, they turn into powerful effector cells that rapidly proliferate and kill the pathogen. Their fellow ...

Molecular pathway that impacts pancreatic cancer progression and response to treatment detailed

2024-06-06

CHAPEL HILL, North Carolina – Researchers at UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center and colleagues have established the most comprehensive molecular portrait of the workings of KRAS, a key cancer-causing gene or "oncogene," and how its activities impact pancreatic cancer outcomes. Their findings could help to better inform treatment options for pancreatic cancer, which is the third leading cause of all cancer deaths in the United States.

The research was published as two separate articles in Science.

“Because ...

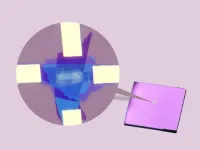

Ferroelectric material is now fatigue-free

2024-06-06

Researchers at the Ningbo Institute of Materials Technology and Engineering (NIMTE) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, in collaboration with research groups from the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China and Fudan University, have developed a fatigue-free ferroelectric material based on sliding ferroelectricity.

The study was published in Science.

Ferroelectric materials have switchable spontaneous polarization that can be reversed by an external electric field, which have been widely applied to non-volatile memory, sensing, and ...

Marsupials key to discovering the origin of heater organs in mammals

2024-06-06

Around 100 million years ago, a remarkable evolutionary shift allowed placental mammals to diversify and conquer many cold regions of our planet. New research from Stockholm University shows that the typical mammalian heater organ, brown fat, evolved exclusively in modern placental mammals.

In collaboration with the Helmholtz Munich and the Natural History Museum Berlin in Germany, and the University of East Anglia in the U.K., the Stockholm research team demonstrated that marsupials, our distant relatives, possess a not fully evolved form of brown fat. They discovered that the pivotal heat-producing protein called ...

Epstein-Barr Virus and brain cross-reactivity: possible mechanism for Multiple Sclerosis

2024-06-06

The role that Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) plays in the development of multiple sclerosis (MS) may be caused a higher level of cross-reactivity, where the body’s immune system binds to the wrong target, than previously thought.

In a new study published in PLOS Pathogens, researchers looked at blood samples from people with multiple sclerosis, as well as healthy people infected with EBV and people recovering from glandular fever caused by recent EBV infection. The study investigated how the immune system deals with EBV infection as part of worldwide efforts to understand how this common virus can lead to the development of multiple ...

Fish out of water: How killifish embryos adapted their development

2024-06-06

The annual killifish lives in regions with extreme drought. A research group at the University of Basel now reports in “Science” that the early embryogenesis of killifish diverges from that of other species. Unlike other fish, their body structure is not predetermined from the outset. This could enable the species to survive dry periods unscathed.

The turquoise killifish inhabits areas characterized by extreme conditions. The species, native to Africa, can survive prolonged periods of drought ...

Novel AI method could improve tissue, tumor analysis and advance treatment of disease

2024-06-06

Researchers at the University of Michigan and Brown University have developed a new computational method to analyze complex tissue data that could transform our current understanding of diseases and how we treat them.

Integrative and Reference-Informed tissue Segmentation, or IRIS, is a novel machine learning and artificial intelligence method that gives biomedical researchers the ability to view more precise information about tissue development, disease pathology and tumor organization.

The findings are published ...

Omega-3 therapy prevents birth-related brain injury in newborn rodents

2024-06-06

NEW YORK, NY--An injectable emulsion containing two omega-3 fatty acids found in fish oil markedly reduced brain damage in newborn rodents after a disruption in the flow of oxygen to the brain near birth, a study by researchers at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons has found.

Brain injury due to insufficient oxygen is a severe complication of labor and delivery that occurs in one to three out of every 1,000 live births in the United States. Among babies who survive, the condition can lead to cerebral palsy, cognitive disability, epilepsy, pulmonary hypertension, and neurodevelopmental conditions.

“Hypoxic ...

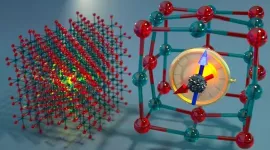

Calcium oxide’s quantum secret: nearly noiseless qubits

2024-06-06

Calcium oxide is a cheap, chalky chemical compound commonly used in the manufacturing of cement, plaster, paper, and steel. But the material may soon have a more high-tech application.

UChicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering researchers and their collaborator in Sweden have used theoretical and computational approaches to discover how tiny, lone atoms of bismuth embedded within solid calcium oxide can act as qubits — the building blocks of quantum computers and quantum communication devices. These qubits are described today in Nature Communications.

“This system has even better properties than we expected,” said Giulia Galli, Liew Family Professor ...

Innovative combination therapy shows promise for bladder cancer patients unresponsive to standard treatment

2024-06-06

TAMPA, Fla. (June 6, 2024) — In a groundbreaking advance that could revolutionize bladder cancer treatment, a novel combination of cretostimogene grenadenorepvec and pembrolizumab has shown remarkable efficacy in patients with Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG)-unresponsive non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Results from the phase 2 CORE-001 trial, published today in Nature Medicine, reveal a significant improvement in complete response rates and long-term disease control, offering new hope for patients with this challenging condition who face limited treatment options.

The trial included patients with BCG-unresponsive carcinoma in situ of the bladder, a condition that is notoriously ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Under the Lens: Microbiologists Nicola Holden and Gil Domingue weigh in on the raw milk debate

Science reveals why you can’t resist a snack – even when you’re full

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

[Press-News.org] Planet-forming disks around very low-mass stars are differentJWST discovers a large variety of carbon-rich gases that serve as ingredients for future planets around a very low-mass star