(Press-News.org) It’s an unusual collaboration. Botanists and archaeologists don’t often work together, unless they’re studying the way people have used plants through time. But a new four-year grant from the National Science Foundation is shaking things up. It provides more than $1 million to study how Mediterranean plants that people have largely ignored evolved and diversified in one of the most formative periods of human history.

“The Mediterranean is at the crossroads of Europe,” said Nicolas Gauthier, curator of artificial intelligence at the Florida Museum of Natural History and co-principal investigator on the grant. “It’s the nexus of social, climatic and environmental changes that occurred across these regions.”

Researchers from the Florida Museum, Southern Illinois University and the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History will focus on a hyper-diverse group of herbs called bellflowers. Their primary goals are to understand the relationships between bellflower species, when and where they originated in the Mediterranean and how human activity has inadvertently altered the diversity and distribution of this group over the last several thousand years.

If it works, investigators say they’ll have created a playbook that can be used to answer similar questions in any region for which there is sufficient historical information about human activity.

“This is data that we don’t traditionally use in an evolutionary context,” said principal investigator Nico Cellinese, curator of herbarium and informatics at the Florida Museum. “We intuitively know that landscapes have been manipulated and transformed by humans, but we don’t know exactly how these changes have affected the distribution of different lineages of plants and animals.”

Bellflowers are the perfect candidate for this initial study. They diversified throughout the Mediterranean before the arrival of humans, have generally narrow distributions — making it easier to trace their history of dispersal — and they don’t have any direct application to agriculture.

“It’s unlike other cases, such as cultivated grass species that humans moved around,” Gauthier said. “We can use bellflowers as a tracer. They haven’t been directly impacted by humans but could potentially tell us about the cascading impacts on ecosystems from humans.”

Even before humans showed up on the scene, the Mediterranean was a hotbed of biological activity and environmental change. Around 5.9 million years ago, the Strait of Gibraltar between Europe and Africa was sealed off. Dry conditions in the region meant there was little water to replenish the Mediterranean Sea, and much of it subsequently evaporated. This killed most of the organisms that lived inside it and left behind thick slabs of salt nearly two miles thick in some places.

Areas that are today occupied by islands, such as the Aegean archipelago, were part of one large landmass connected to the rest of Europe and Africa, allowing plants and animals to move freely. Less than a million years later, the dam broke, and water from the Atlantic poured into the Mediterranean during a period of months to years called the Zanclean flood.

As the waters rose, plants and animals were again isolated on islands, where they evolved into new species.

“Some bellflower species are endemic to one or two islands, but is this endemism a consequence of geological or human activity? This is something that no one has ever really looked at in detail,” Cellinese said.

Investigators on the grant will combine a new and unpublished archaeological dataset of human activity in the Mediterranean with genetic data to determine when bellflowers evolved and where they likely grew.

“We have a record of the timing of human colonization on different islands. This is something that you don’t get in mainland areas, where we can never quite know for certain when human activity started or stopped,” Gauthier said.

With that information in hand, the next phase of the project will incorporate computer modeling to determine which environments are suitable for different bellflower species to grow in. Often, when a plant is absent from a suitable, nearby environment, it indicates human activity or other factors are restricting its range.

Gauthier will further fine-tune these analyses with artificial intelligence. Using a technique called downscaling, AI can take information on global climate change and translate it into the scale of local landscapes that plants actually experience, Gauthier said.

“You can know that it might be two degrees warmer in the northern hemisphere, but what does that mean about the west-facing slope of this one mountain that is next to the ocean? We can use AI to bridge that gap in scale.”

The Mediterranean Sea is one of several regions worldwide that have similar climates and similar problems. Following the completion of this project, Gauthier said these areas should be among the first for which this type of research is conducted.

“This biome is one of the most threatened by contemporary climate change,” he said. “They’re places where we see warming happening faster than the rest of the world, because they’re so sensitive to regional circulation patterns. This project is a test case for how these kinds of ecosystems will respond to climate change in the future.”

Torben Rick of the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History, Jennifer Weber of Southern Illinois University and Andrew Crowl of the University of Florida are also co-principal investigators on the grant.

END

Botanists and archaeologists receive National Science Foundation grant to study Mediterranean history

2024-06-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Silkworms help grow better organ-like tissues in labs

2024-06-06

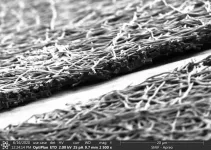

DURHAM, N.C. -- Biomedical engineers at Duke University have developed a silk-based, ultrathin membrane that can be used in organ-on-a-chip models to better mimic the natural environment of cells and tissues within the body. When used in a kidney organ-on-a-chip platform, the membrane helped tissues grow to recreate the functionality of both healthy and diseased kidneys.

By allowing the cells to grow closer together, this new membrane helps researchers to better control the growth and function of the key cells and tissues of any organ, enabling them to more accurately model a wide range of diseases and test therapeutics.

The research appears June 4 in the journal Science Advances.

Often ...

Scientists ‘read’ the messages in chemical clues left by coral reef inhabitants

2024-06-06

What species live in this coral reef, and are they healthy? Chemical clues emitted by marine organisms might hold that information. But in underwater environments, invisible compounds create a complex “soup” that is hard for scientists to decipher. Now, researchers in ACS’ Journal of Proteome Research have demonstrated a way to extract and identify these indicator compounds in seawater. They found metabolites previously undetected on reefs, including three that may represent different reef organisms.

Plants and animals living in coral reefs release various substances, from complex macromolecules to individual amino acids, into the surrounding water. To determine ...

Identifying risk factors for native coronary atherosclerosis progression after percutaneous coronary intervention

2024-06-06

https://www.scienceopen.com/hosted-document?doi=10.15212/CVIA.2024.0033

Announcing a new article publication for Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications journal. This study was aimed at investigating factors influencing the progression of native coronary atherosclerosis after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

A cohort of 462 patients was classified into progressive (n = 73) or non-progressive (n = 389) groups according to the presence of native coronary atherosclerosis progression on coronary angiography. ...

Mapping noise to improve quantum measurements

2024-06-06

One of the biggest challenges in quantum technology and quantum sensing is “noise”–seemingly random environmental disturbances that can disrupt the delicate quantum states of qubits, the fundamental units of quantum information. Looking deeper at this issue, JILA Associate Fellow and University of Colorado Boulder Physics Assistant Professor Shuo Sun recently collaborated with Andrés Montoya-Castillo, Assistant Professor of Chemistry, and his team to develop a new method for better understanding and controlling this noise, potentially paving the way for significant advancements in quantum computing, ...

Tiny predator owes its shape-shifting ability to “origami-like” cellular architecture

2024-06-06

For a tiny hunter of the microbial world that relies on extending its neck up to 30 times its body length to release its deadly attack, intricate origami-like cellular geometry is key. This geometry enables the rapid hyperextensibility of the neck-like protrusion, for single-celled predator Lacrymaria olor, a new study reports. The findings not only explain L. olor’s extreme shape-shifting ability but also hold potential for inspiring innovations in soft-matter engineering or the design of robotic systems. Single-celled protists are well known for their ability to perform dynamic morphological changes in ...

Widespread use of high-assay low-enriched uranium raises significant nuclear security concerns

2024-06-06

In a Policy Forum, R. Scott Kemp and colleagues argue that promoting new nuclear reactor technologies using high-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU) threatens the international system of controls that has prevented nuclear weapons proliferation for over 30 years. “Governments and others promoting the use of HALEU have not carefully considered the potential proliferation and terrorism risks that the wide adoption of this fuel creates,” write Kemp et al. The authors warn that if HALEU becomes a standard reactor ...

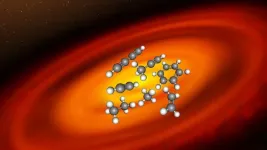

JWST uncovers features of very-low-mass star’s protoplanetary disk that influence planet composition

2024-06-06

James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) observations have revealed abundant hydrocarbons in the protoplanetary disk surrounding a young, very-low-mass star – findings that provide novel insights into the chemical environment from which many terrestrial planets, in particular, are born. Planets form in disks of gas and dust that orbit young stars. Observations show that terrestrial planets form more efficiently than gas giant planets around very-low-mass stars (VLMSs) – those with less than 0.3 solar masses. Although the chemical compositions of the inner disk regions around higher mass stars ...

Mammalian adipose tissue thermogenesis evolved in eutherian mammals

2024-06-06

Heat production in fat tissue, a trait also known as adipose tissue thermogenesis, evolved over two stages in mammals, fully developing in eutherian mammals after the group’s evolutionary divergence from marsupials, according to a new study. The results could provide insights that inform future therapies related to metabolism and obesity. Many organisms produce heat internally to regulate body temperature. It is thought that the evolution of the ability to maintain high body temperatures provided ...

The first example of cellular origami

2024-06-06

“There are some things in life you can watch and then never unwatch,” said Manu Prakash, associate professor of bioengineering at Stanford University, calling up a video of his latest fascination, the single-cell organism Lacrymaria olor, a free-living protist he stumbled upon playing with his paper Foldscope. “It’s … just … it’s mesmerizing.”

“From the minute Manu showed it to me, I have just been transfixed by this cell,” said Eliott Flaum, a graduate student ...

Planet-forming disks around very low-mass stars are different

2024-06-06

Planets form in disks of gas and dust, orbiting young stars. The MIRI Mid-INfrared Disk Survey (MINDS), led by Thomas Henning from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA) in Heidelberg, Germany, aims to establish a representative disk sample. By exploring their chemistry and physical properties with MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument) on board the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), the collaboration links those disks to the properties of planets potentially forming there. In a new study, a team of researchers ...