(Press-News.org)

An awkward beat doesn't help on the dance floor, but it could help people who are recovering from mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI).

Publishing online today (June 11, 2024) in the Journal of Neurotrauma, Virginia Tech scientists with the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC show that specifying the timing pattern of neurostimulation – impulses used to activate the brain’s own electrical signaling mechanisms – can rebalance the strength of synaptic connections between nerve cells, selectively up- or down-regulating those connections. While the timing pattern of electrical signaling is important in the normal brain, it also plays a role in regulating the strength of synaptic connections after brain injury, particularly strengthening them with the same patterns that would otherwise weaken those connections in the normal brain.

The study underscores the importance of considering the use of more natural, noisier patterns of impulses of activity for neurostimulation in attempts to more effectively treat brain disorders including, but not limited to, concussions and other mild traumatic brain injuries in people. More than 2.1 million head traumas are treated in U.S. emergency departments each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with many other such injuries occurring without medical attention.

“Our results suggest that we may be able to use different patterns of brain stimulation to help treat mild traumatic brain injuries,” said Michael Friedlander, a co-corresponding author on the paper in whose laboratory the work was carried out. Friedlander is the executive director of the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC and Virginia Tech’s Vice President for Health Sciences and Technology.

“By adjusting things like the timing, frequency, and consistency of the stimulation, we might be able to strengthen specific connections in the brain, which could help improve brain function after injury. It has not escaped our attention that the electrical and synaptic signaling in the living brain is generally anything but regular,” Friedlander said. “Thus, we wanted to build on that natural noisiness that the brain uses to see if patterns that mimic those might have some intrinsic capacity to activate signaling pathways to re-adjust strengths between nodes in living neuronal networks that have otherwise been functionally compromised such as occurs after injury.”

Brain stimulation is increasingly being used in the clinic to treat a variety of neurological and psychiatric disorders such as depression, Parkinson’s disease, chronic pain, and Alzheimer’s disease but little attention has been paid to the patterns of the stimulation other than frequency.

“While our study in laboratory rats is directed specifically at mild traumatic brain injury, it may also provide useful information to be applied to treatments of other brain conditions in people,” Friedlander said.

The study is among the first to look at the effects of systematically and precisely controlling the timing patterns of neurostimulation.

Notably, the researchers found that irregular patterns at certain frequencies appear to affect injured brains differently than normal brains, strengthening their connections with other nerve cells, while in the normal brain, those same patterns weakened the connections.

“Neurostimulation can be delivered in regular intervals like a metronome, but it can also be delivered in a way that is more irregular,” said Quentin Fischer, research assistant professor at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute in the Friedlander laboratory and co-corresponding author of the study.

“It is somewhat like the difference between a very organized concerto piece, and jazz, where the musicians are playing around with the patterns,” Fischer said. “We found that highly irregular patterns of stimulation in the normal brain led to a decrease in the strength of connections between neurons, but in the injured brain, that same irregular pattern of stimulation, at the same frequency and continuity, resulted in a strengthening of those connections.”

The findings underscore the importance of timing signals to optimize neurostimulation therapies for mTBI and other brain disorders, suggesting potential avenues for more effective treatment strategies.

“There is a dramatic difference between the normal brain and the injured brain in respect to how the synapses respond to different patterns of stimulation,” Friedlander said. “A mild traumatic brain injury, despite its name, can have serious and lasting effects on cognitive function, mood, and overall quality of life. This highlights the critical importance of understanding the best approaches for delivering optimized therapeutic neurostimulation.”

END

UPTON, N.Y. — Efforts to achieve net-zero carbon emissions from transportation fuels are increasing demand for oil produced by nonfood crops. These plants use sunlight to power the conversion of atmospheric carbon dioxide into oil, which accumulates in seeds. Crop breeders interested in selecting plants that produce a lot of oil look for yellow seeds. In oilseed crops like canola, yellow-seeded varieties generally produce more oil than their brown-seeded counterparts. The reason: The protein responsible for brown seed color — which yellow-seeded plants lack — also plays a key role in oil production.

Now, plant biochemists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven ...

URBANA, Ill. -- Following decades of decline, even fewer birds will darken North American skies by the end of the century, according to a new analysis by scientists at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Their study is the first to examine the long-term effects of climate change on the abundance and diversity of bird groups across the continent as a whole while accounting for additional factors that put birds at risk, such as pesticides, pollution, land use change, and habitat loss.

“Many studies try to attribute causes like climate ...

As space travel becomes more frequent, a new biomarker tool was developed by an international team of researchers to help improve the growing field of aerospace medicine and the health of astronauts.

Dr. Guy Trudel (Professor in the Faculty of Medicine), Odette Laneuville (Associate Professor, Faculty of Science, and Director of the Biomedical Sciences) and Dr. Martin Pelchat (Associate Professor in the Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology and Immunology) are among the contributors to an international ...

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Haiku poems have reflected humans’ experiences in nature for hundreds of years, including observations of bugs and other wildlife. Recently, Penn State researchers analyzed which insects were mentioned the most in haiku — with butterflies, fireflies and singing insects such as crickets topping the list.

Haiku are three-line poems with five syllables in the first and third lines, and seven syllables in the second line.

In their study of nearly 4,000 haiku, recently published in the journal PLOS ONE, the researchers also found that aquatic arthropods — such as caddisflies, stoneflies and fishflies — were mentioned the ...

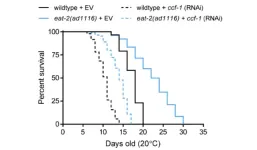

“[...] it appears that the CCR4-NOT complex can influence longevity in a multitude of manners [...]”

BUFFALO, NY- June 11, 2024 – A new editorial paper was published in Aging (listed by MEDLINE/PubMed as "Aging (Albany NY)" and "Aging-US" by Web of Science) Volume 16, Issue 10, entitled, “CCR4-NOT complex in stress resistance and longevity in C. elegans.”

The ability to mount an adaptive response to environmental stress is crucial in organismal survival and overall fitness. In the context of aging, many genes that mediate resistance to stressors are also important in longevity, and aging has been shown to cause ...

Subscribe to UCSF News

Note to Editors: Speaker bios are available in our media kit

UCSF Health and UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospitals celebrated the signing of a Community Workforce Agreement (CWA) on June 11, agreeing to prioritize local union workers for the construction of a proposed landmark hospital building and related site improvements on its Oakland site.

The agreement, signed by the Building and Construction Trades Council of Alameda County (BTCA) and the project’s general contractor, Rudolph and Sletten, confirms a mutual understanding to hire union workers and follow union hiring practices. An additional agreement was signed by Overaa Construction, ...

ITHACA, N.Y. – An artificial intelligence-powered virtual teammate with a female voice boosts participation and productivity among women on teams dominated by men, according to new Cornell University research.

The findings suggest that the gender of an AI’s voice can positively tweak the dynamics of gender-imbalanced teams and could help inform the design of bots used for human-AI teamwork, researchers said.

The findings mirror previous research that shows minority teammates are more likely to participate if the team adds members similar to them, said Angel Hsing-Chi Hwang, postdoctoral associate in information science and ...

The human visual system is a dominant part of the brain’s processes and navigation of the world. To better understand an aspect of this system, researchers from Drexel University’s College of Nursing and Health Professions examined how life experiences impact a person’s perception of imagery – specifically decorated masks.

The study, published in Frontiers in Psychology, examined viewer responses to images of distressing and neutrally decorated masks and whether personal life history, particularly past ...

TAMPA, Fla. — Leptomeningeal disease is a rare but lethal complication faced by late-stage melanoma patients. It occurs when cancer cells spread to the membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, or the leptomeninges. This condition, which affects 5% to 8% of melanoma patients, often leads to rapid deterioration and is notoriously resistant to therapies. However, a new Moffitt Cancer Center study, published today in Cell Reports Medicine, uncovers the mechanisms that drive this drug resistance, offering new avenues ...

Iran’s water policy is discriminatory and an example of environmental racism, with specific regions and ethnic groups deliberately impoverished, damaged and threatened by policymakers, a new study says.

Water scarcity lies at the core of Iran’s environmental crises. Approximately 28 million of Iran’s 85 million residents reside in water-stressed areas, a situation identified as ‘water bankruptcy’. This is particularly the case in the central, industrialised regions.

Other “donor basin” regions – which have ...