(Press-News.org) In recent years global warming has left its mark on the Antarctic ice sheets. The "eternal" ice in Antarctica is melting faster than previously assumed, particularly in West Antarctica more than East Antarctica. The root for this could lie in its formation, as an international research team led by the Alfred Wegener Institute has now discovered: sediment samples from drill cores combined with complex climate and ice-sheet modelling show that permanent glaciation of Antarctica began around 34 million years ago – but did not encompass the entire continent as previously assumed, but rather was confined to the eastern region of the continent (East Antarctica). It was not until at least 7 million years later that ice was able to advance towards West Antarctic coasts. The results of the new study show how substantially differently East and West Antarctica react to external forcing, as the researchers describe in the prestigious journal Science.

Around 34 million years ago, our planet underwent one of the most fundamental climate shifts that still influences global climate conditions today: the transition from a greenhouse world, with no or very little accumulation of continental ice, to an icehouse world, with large permanently glaciated areas. During this time, the Antarctic ice sheet built up. How, when and, above all, where, was not yet known due to a lack of reliable data and samples from key regions, especially from West Antarctica, that document the changes in the past. Researchers from the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) have now been able to close this knowledge gap, together with colleagues from the British Antarctic Survey, Heidelberg University, Northumbria University (UK), and the MARUM - Center for Marine Environmental Sciences at the University of Bremen, in addition to collaborators from the Universities in Aachen, Leipzig, Hamburg, Bremen, and Kiel, as well as the University of Tasmania (Australia), Imperial College London (UK), Université de Fribourg (Switzerland), Universidad de Granada (Spain), Leicester University (UK), Texas A&M University (USA), Senckenberg am Meer, and the Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources in Hanover, Germany.

Based on a drill core that the researchers retrieved using the MARUM-MeBo70 seafloor drill rig in a location offshore the Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers on the Amundsen Sea coast of West Antarctica, they were able to establish the history of the dawn of the icy Antarctic continent for the first time. Surprisingly, no signs of the presence of ice can be found in this region during the first major phase of Antarctic glaciation. “This means that a large-scale, permanent first glaciation must have begun somewhere in East Antarctica,” says Dr Johann Klages, geologist at the AWI who led the research team. This is because West Antarctica remained ice-free during this first glacial maximum. At this time, it was still largely covered by dense broadleaf forests and a cool-temperate climate that prevented ice from forming in West Antarctica.

East and West Antarctica react very different to external conditions

In order to better understand where the first permanent ice formed in Antarctica, the AWI paleoclimate modelers combined the newly available data together with existing data on air and water temperatures and the occurrence of ice. “The simulation has supported the results of the geologists' unique core,” says Prof Dr Gerrit Lohmann, paleoclimate modeler at the AWI. “This completely changes what we know about the first Antarctic glaciation.” According to the study, the basic climatic conditions for the formation of permanent ice only prevailed in the coastal regions of the East Antarctic Northern Victoria Land. Here, moist air masses reached the strongly rising Transantarctic Mountains – ideal conditions for permanent snow and subsequent formation of ice caps. From there, the ice sheet spread rapidly into the East Antarctic hinterland. However, it took some time before it reached West Antarctica: “It wasn't until about seven million years later that conditions allowed for advance of an ice sheet to the West Antarctic coast,” explains Hanna Knahl, a paleoclimate modeler at the AWI. “Our results clearly show how cold it had to get before the ice could advance to cover West Antarctica that, at that time, was already below sea level in many parts.” What the investigations also impressively show is how different the two regions of the Antarctic ice sheet react to external influences and fundamental climatic changes. “Even a slight warming is enough to cause the ice in West Antarctica to melt again - and that's exactly where we are right now,” adds Johann Klages.

The findings of the international research team are critical for understanding the extreme climate transition from the greenhouse climate to our current icehouse climate. Importantly, the study also provides new insight that allows climate models to simulate more accurately how permanently glaciated areas affect global climate dynamics, that is the interactions between ice, ocean and atmosphere. This is of crucial importance, as Johann Klages says: “Especially in light of the fact that we could be facing such a fundamental climate change again in the near future.”

Using new technology to gain unique insights

The researchers were able to close this knowledge gap with the help of a unique drill core that they retrieved during the expedition PS104 on the research vessel Polarstern in West Antarctica in 2017. The MARUM-MeBo70 drill rig developed at MARUM in Bremen was used for the first time in Antarctica. The seabed off the West Antarctic Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers is so hard that it was previously impossible to reach deep sediments using conventional drilling methods. The MARUM-MeBo70 has a rotating cutterhead, which made it possible to drill about 10 meters into the seabed and retrieve the samples.

The research project, and the Polarstern expedition PS104 in particular, was funded by the AWI, MARUM, the British Antarctic Survey, and the NERC UK-IODP Programme.

Original publication:

J. P. Klages, C.-D. Hillenbrand, S. M. Bohaty, U. Salzmann, T. Bickert, G. Lohmann, H. S. Knahl, P. Gierz, L. Niu, J. Titschack, G. Kuhn, T. Frederichs, J. Müller, T. Bauersachs, R. D. Larter, K. Hochmuth, W. Ehrmann, G. Nehrke, F. J. Rodríguez-Tovar, G. Schmiedl, S. Spezzaferri, A. Läufer, F. Lisker, T. van de Flierdt, A. Eisenhauer, G. Uenzelmann-Neben, O. Esper, J. A. Smith, H. Pälike, C. Spiegel, R. Dziadek, T. A. Ronge, T. Freudenthal, and K. Gohl. Ice sheet-free West Antarctica during peak early Oligocene glaciation. (2024). 10.1126/science.adj3931. This paper will be published online by the journal Science on THURSDAY, 04 July 2024.

Further material:

More information, including a copy of the paper and pictures, can be found online at the Science press package at https://www.eurekalert.org/press/scipak/.

END

The dawn of the Antarctic ice sheets

For the first time, the recovery of unique geological samples combined with sophisticated modelling provides surprising insights into when and where today's Antarctic ice sheet formed

2024-07-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Not so selfish after all: Viruses use freeloading genes as weapons

2024-07-04

Curious bits of DNA tucked inside genomes across all kingdoms of life historically have been disregarded since they don’t seem to have a role to play in the competition for survival. Or so researchers thought.

These DNA pieces came to be known as “selfish genetic elements” because they exist, as far as scientists could tell, to simply reproduce and propagate themselves, without any benefit to their host organisms. They were seen as genetic hitchhikers that have been inconsequentially passed ...

Researchers identify unknown signalling pathway in the brain responsible for migraine with aura

2024-07-04

A previously unknown mechanism by which proteins from the brain are carried to a particular group of sensory nerves causes migraine attacks, a new study shows. This may pave the way for new treatments for migraine and other types of headaches.

More than 800,000 Danes suffer from migraines – a condition characterised by severe headache in one side of the head. In around a fourth of all migraine patients, headache attacks are preceded by aura – symptoms from the brain such as temporary visual or sensory disturbances preceding the migraine attack by 5-60 minutes.

While ...

Music: Song melodies have become simpler since 1950

2024-07-04

The complexity of the melodies of the most popular songs each year in the USA — according to the Billboard year-end singles charts — has decreased since 1950, a study published in Scientific Reports suggests.

Madeline Hamilton and Marcus Pearce analysed the most prominent melodies (usually the vocal melody) of songs that reached the top five positions of the US Billboard year-end singles music charts each year between 1950 and 2022. They found that the complexity of song rhythms and pitch arrangements decreased over this period as the average number of notes ...

Effects of visual and auditory instructions on space station procedural tasks

2024-07-04

Firstly, the authors provided a detailed explanation of the experimental methods and procedures. This study recruited 30 healthy subjects (15 males and 15 females), aged between 20 to 50 years, with an average age of 42 ± 6.58 years. All participants had no severe visual or auditory impairments and were right-handed. The subjects met the biometric standards for astronaut candidates and were rigorously screened. The experiment used Unity 3D to model the space station, simulating the internal scenes of the space station. The subjects started from the core node module and found the laboratory module I, where they operated the Space Raman Spectrometer ...

Norway can lead the fight against plastic pollution

2024-07-04

Plastic items from around the world are continuously washing ashore on Norwegian coastlines. This reflects a much larger systemic issue facing the nations of the world.

Scientists have long reported the consequences of plastic pollution and the urgent need for intervention, but global plastic production and consumption continue to rise.

This underscores the importance of Norway’s advocacy for a global agreement that guarantees stopping the flow of plastics into the environment.

But Norway also has a responsibility in generating plastic pollution.

In a study conducted ...

Decolonizing the Tropical Ecology curriculum

2024-07-04

A new study of curriculum reading material at the University of Glasgow finds that 94% of recommended Tropical Ecology authors are white, and that 80% of authors are affiliated with universities outside of the tropics. Dr Stewart White, Senior Lecturer at the School of Biodiversity, One Health and Veterinary Medicine at the University of Glasgow, UK, intends to change that.

“Tropical rainforest research was long the preserve of rich white men and the resulting literature was the same,” says Dr White. “This historical bias in tropical research and publication is still ...

Exploring the casque anatomy of aerial jousting helmeted hornbills

2024-07-04

New research reveals how the surprising internal anatomy of the helmeted hornbill’s casque allows it to withstand damage during aerial jousting battles with rivals. Researchers hope that this new understanding can help to conserve this critically endangered species, as well as provide new insights into developing impact-resistant bio-mimetic materials.

“When I started in Hong Kong, I visited City University of Hong Kong (HKU)’s conservation forensics group to chat about their research and they introduced me to this amazing bird, to its ...

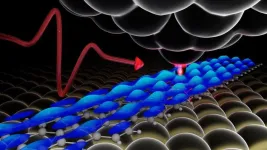

A New Blue: Mysterious origin of the ribbontail ray’s electric blue spots revealed

2024-07-04

Researchers have discovered the unique nanostructures responsible for the electric blue spots of the bluespotted ribbontail ray (Taeniura lymma), with possible applications for developing chemical-free colouration. The team are also conducting ongoing research into the equally enigmatic blue colouration of the blue shark (Prionace glauca).

Skin colouration plays a key role in organismal communication, providing life-critical visual clues that can warn, attract or camouflage. Bluespotted ribbontail ...

Cool roofs are best at beating cities’ heat

2024-07-04

Painting roofs white or covering them with a reflective coating would be more effective at cooling cities like London than vegetation-covered “green roofs,” street-level vegetation or solar panels, finds a new study led by UCL researchers.

Conversely, extensive use of air conditioning would warm the outside environment by as much as 1 degree C in London’s dense city centre, the researchers found.

The research, published in Geophysical Research Letters, used a three-dimensional urban climate model of Greater London to test the thermal effects of different passive and active urban heat management systems, including painted “cool roofs,” rooftop solar panels, ...

Single atoms show their true color

2024-07-04

One of the challenges of cramming smarter and more powerful electronics into ever-shrinking devices is developing the tools and techniques to analyze the materials that make them up with increasingly intimate precision.

Physicists at Michigan State University have taken a long-awaited step on that front with an approach that combines high-resolution microscopy with ultrafast lasers.

The technique, described in the journal Nature Photonics, enables researchers to spot misfit atoms in semiconductors with unparalleled precision. Semiconductor physics labels these atoms as “defects,” which sounds negative, but they’re ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

GLP-1 drugs associated with reduced need for emergency care for migraine

New knowledge on heritability paves the way for better treatment of people with chronic inflammatory bowel disease

Under the Lens: Microbiologists Nicola Holden and Gil Domingue weigh in on the raw milk debate

Science reveals why you can’t resist a snack – even when you’re full

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

[Press-News.org] The dawn of the Antarctic ice sheetsFor the first time, the recovery of unique geological samples combined with sophisticated modelling provides surprising insights into when and where today's Antarctic ice sheet formed