(Press-News.org) A new way to store carbon captured from the atmosphere developed by researchers from The University of Texas at Austin works much faster than current methods without the harmful chemical accelerants they require.

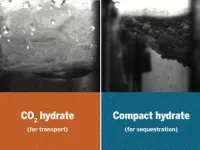

In new research published in ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, the team developed a technique for ultrafast formation of carbon dioxide hydrates. These unique ice-like materials can bury carbon dioxide in the ocean, preventing it from being released into the atmosphere.

“We’re staring at a huge challenge — finding a way to safely remove gigatons of carbon from our atmosphere — and hydrates offer a universal solution for carbon storage. For them to be a major piece of the carbon storage pie, we need the technology to grow them rapidly and at scale,” said Vaibhav Bahadur, a professor in the Walker Department of Mechanical Engineering who led the research. “We’ve shown that we can quickly grow hydrates without using any chemicals that offset the environmental benefits of carbon capture.”

Carbon dioxide is the most common greenhouse gas and a major driver of climate change. Carbon capture and sequestration takes carbon out of the atmosphere and stores it permanently. And it is seen as a critical aspect of decarbonizing our planet.

Today, the most common carbon storage method involves injecting carbon dioxide into underground reservoirs. This technique has the dual benefits of trapping carbon and also increasing oil production.

However, this technique faces significant issues, including carbon dioxide leakage and migration, groundwater contamination and seismic risks associated with injection. Many parts of the world also lack suitable geologic features for reservoir injection.

Hydrates represent a “plan B” for gigascale carbon storage, Bahadur said, but they could become “plan A” if some of the main issues can be overcome. Until now, the process of forming these carbon-trapping hydrates has been slow and energy-intensive, holding it back as a large-scale means of carbon storage.

In this new study, the researchers achieved a sixfold increase in the hydrate formation rate compared with previous methods. The speed combined with the chemical-free process make it easier to use these hydrates for mass-scale carbon storage.

Magnesium represents the “secret sauce” in this research, acting as a catalyst that eliminates the need for chemical promoters. This is aided by high flow rate bubbling of CO2 in a specific reactor configuration. This technology works well with seawater, which makes it easier to implement because it doesn’t rely on complex desalination processes to create fresh water.

"Hydrates are attractive carbon storage options since the seabed offers stable thermodynamic conditions, which protects them from decomposing.” Bahadur said. “We are essentially making carbon storage available to every country on the planet that has a coastline; this makes storage more accessible and feasible on a global scale and brings us closer to achieving a sustainable future."

The implications of this breakthrough extend beyond carbon sequestration. Ultrafast formation of hydrates has potential applications in desalination, gas separation and gas storage, offering a versatile solution for various industries.

The researchers and UT have filed for a pair of patents related to the technology, and the team is considering a startup to commercialize it.

END

New carbon storage technology is fastest of its kind

2024-07-09

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Socioeconomic status significantly affects fertility treatment outcomes, new study shows

2024-07-09

Novel research, presented today at the ESHRE 40th Annual Meeting in Amsterdam, reveals significant social disparities in achieving live births following assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatment. Women with a research education (PhD) were over three times more likely to achieve a live birth compared to those with a primary school education, while women in the highest income group were twice as likely than those in the lowest income group [1].

Conducted by researchers from the University of Copenhagen and Copenhagen University Hospital (Rigshospitalet), the national, register-based study analysed data from 68,738 women aged 18-45 who underwent ...

IVF and IUI treatment cycles increase across Europe, along with stable pregnancy rates

2024-07-09

Women in Europe are receiving more cycles of in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and intrauterine insemination (IUI), according to data presented today at the ESHRE 40th Annual Meeting in Amsterdam [1].

Preliminary data from the ESHRE European IVF Monitoring (EIM) Consortium [2] reveals a steady and progressive rise in the use of Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART). In 2021, a total of 1 103,633 ART treatment cycles were reported by 1,382 clinics across 37 European countries – a 20% increase from the 919,364 cycles reported in 2020, keeping in mind that this was the year COVID affected the number ...

New 3D imaging method offers promise of better IVF outcomes

2024-07-09

Innovative research, presented today at the ESHRE 40th Annual Meeting in Amsterdam, has introduced a novel 3D imaging model designed to identify features of blastocysts – the early stage of development for an implanted embryo – associated with successful pregnancies. This new approach could transform current blastocyst selection methods, and open avenues for increased pregnancy rates [1].

The shape and structure of blastocysts can predict the success of a pregnancy, aiding blastocyst selection for in vitro fertilisation (IVF). However, selecting ...

Brain & Life® announces new Editor-in-Chief

2024-07-08

MINNEAPOLIS – The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) has named a new editor-in-chief of Brain & Life®, its free patient and caregiver magazine, website and podcast. Sarah Song, MD, MPH, FAAN, an associate professor in the department of neurological sciences at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, will succeed Editor-in-Chief Orly Avitzur, MD, MBA, FAAN, who will complete her 10-year term on December 31, 2024.

Song, a Fellow of the American Academy of Neurology, will be the third editor-in-chief of Brain & Life since the publication began in ...

University of Cincinnati study: Brain organ plays key role in adult neurogenesis

2024-07-08

University of Cincinnati researchers have pioneered an animal model that sheds light on the role an understudied organ in the brain has in repairing damage caused by stroke.

The research was published July 2 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and sought to learn more about how the adult brain generates new neurons to repair damaged tissue.

The research team focused on the choroid plexus, a small organ within brain ventricles that produces the brain’s cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). CSF circulates throughout ...

Small molecules induce trained immunity, opening a new approach to fighting disease

2024-07-08

Vaccines provide a front-line defense against dangerous viruses, training adaptive immune cells to identify and fight specific pathogens.

But innate immune cells — the first responders to any bodily invader — have no such specific long-term memory. Still, scientists have found that they can reprogram these cells to be even better at their jobs, potentially fighting off seasonal scourges like the common cold or even new viral diseases for which vaccines have not yet been developed.

A University of Chicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (PME) team has found several small molecule candidates that induce this trained immunity without the ...

Erasing “bad memories” to improve long term Parkinson’s disease treatment

2024-07-08

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. — Common treatments for Parkinson’s disease can address short-term symptoms but can also cause extensive problems for patients in the long run. Namely, treatments can cause dyskinesia, a form of uncontrollable movements and postures.

In a recent study published in The Journal of Neuroscience, researchers at the University of Alabama at Birmingham took a different approach to dyskinesia and treated it like a “bad motor memory.” They found that blocking a protein called Activin A could halt dyskinesia symptoms ...

Restored oyster sanctuaries host more marine life

2024-07-08

In the campaign to restore Chesapeake Bay, oyster sanctuaries rank among the most hotly contested strategies. But new research suggests these no-harvest areas are working, and not only for the oysters. In a new study published July 4 in Marine Ecology Progress Series, Smithsonian biologists discovered oyster sanctuaries contain more abundant populations of oysters and other animal life—and the presence of two common parasites is not preventing that.

Oysters form the backbone of Chesapeake Bay. Besides injecting millions of dollars into the regional economy each year, they also act as vital habitat and filter feeders that clean the water. But their populations ...

Research spotlight: Machine learning helps identify patients at varying levels of risk for opioid use disorder

2024-07-08

Ronen Rozenblum, PhD, MPH, director of the Unit for Innovative Healthcare Practice & Technology and director of Business Development of the Center for Patient Safety Research and Practice at Brigham and Women's Hospital, and an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, is the principal investigator and senior author of a new study published in JMIR Medical Informatics, “A Machine Learning Application to Classify Patients at Differing Levels of Risk of Opioid Use Disorder: Clinician Based ...

Detroit researchers receive Department of Defense grant to assist in discovering new treatments for ovarian cancer

2024-07-08

DETROIT — Gen Sheng Wu, Ph.D., professor of oncology in the Wayne State University School of Medicine and the Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute, recently received a grant from the U.S. Department of Defense’s Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs.

This four-year, $924,000 grant will benefit Wu’s study, “Targeting Dual-Specificity Phosphatase 1 in Platinum Resistance in Ovarian Cancer,” which aims to discover improved treatments for ovarian cancer.

“Ovarian cancer ...