(Press-News.org) Scientists at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) in Saudi Arabia have developed a tiny “claw machine” that is able to pick up and drop a marble-sized ball in response to exposure to chemical vapors.

The findings, published July 12 in the journal Chem, point to a technique that can enable soft actuators—the parts of a machine that make it move—to perform multiple tasks without the need for additional costly materials. While existing soft actuators can be “one-trick ponies” restricted to one type of movement, this novel composite film contorts itself in different ways depending on the vapor that it is exposed to.

“It can bend and stretch depending on molecular interactions, which is very sophisticated at this size range,” says author Niveen M. Khashab, a Chemistry Professor at KAUST. “We hope our findings will be used to develop advanced soft robotic systems capable of precise and adaptable movements in various environments,” she says, suggesting the systems could be used in medical devices, industrial automation, and tools used to measure temperature, air quality, and humidity.

To test the claw machine’s ability to perform multiple tasks, the researchers first exposed it to acetone. In the presence of this vapor, the device gripped a red cotton ball and stretched so that it could drop it in a box. When the team exposed the machine to ethanol vapor, it grabbed the cotton ball and removed it from the box.

Unlike rigid actuators in “hard robots,” which may be made from metal or tough plastic, soft actuators are flexible, enabling them to perform a range of tasks their rigid counterparts cannot. As a result, soft actuators have been the technology of choice for cutting-edge applications such as precision agriculture, deep-sea exploration, and wearable devices.

But soft actuators are still limited—they can either bend, twist, or stretch, but no one actuator can move in multiple ways, preventing them from performing more complex tasks that would lend them to an even greater range of uses. While researchers have recently experimented with actuator designs to give devices a greater range of motion, many of these strategies involve combining different materials, which makes them costly and difficult to manufacture while increasing their risk for mechanical failure.

To overcome this challenge, Khashab and colleagues developed a claw machine made from a polymer matrix containing molecular cages with the organic compound urea. The researchers chose urea for the cages because the compound can form multiple hydrogen bonds, allowing the urea molecules to rapidly reconfigure when they are exposed to different molecules in vapors. As a result, the material’s properties can be precisely controlled, making it easy to customize.

The findings suggest that the material the machine is made from can be “effectively programmed to achieve complex movements by judiciously controlling the type and the concentration of the vapor stimulus,” the authors write.

“The most remarkable finding was the unique actuation behavior where the soft actuator performed a complex motion involving ‘curvature, stretching, and reverting,’ which had not been reported previously,” says Khashab.

Next, Khashab and colleagues plan to study the claw machine’s energy density and how efficiently it converts energy so that they can enhance its performance, she says. They will also test its ability to produce electrical signals when the soft actuator is combined with materials that generate an electric charge, with the ultimate goal of developing flexible wearable electronic devices, says Khashab.

###

This work was supported by the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST).

Chem, Liu and Fang et al. “Promoting stimuli-responsive motion in soft matter by host-guest interactions” https://www.cell.com/chem/fulltext/S2451-9294(24)00295-X

Chem (@Chem_CP) is the first physical science journal published by Cell Press. A sister journal to Cell, Chem, which is published monthly, provides a home for seminal and insightful research and showcases how fundamental studies in chemistry and its sub-disciplines may help in finding potential solutions to the global challenges of tomorrow. Visit https://www.cell.com/chem. To receive Cell Press media alerts, contact press@cell.com.

END

BALTIMORE, MD, July 12, 2024 — Those living in disadvantaged neighborhoods have significantly higher activity of stress-related genes, new research suggests, which could contribute to higher rates of aggressive prostate cancer in African American men. The study, which was co-led by the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) and Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU), was published today in JAMA Network Open.

African American men have a higher incidence of prostate cancer and are more than twice as likely to die from the disease than White men in the U.S. They are often diagnosed with an ...

Overview:

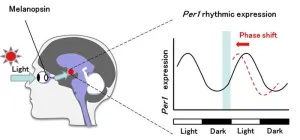

DNA aptamers of melanopsin that regulate the clock hands of biological rhythms were developed by the Toyohashi University of Technology and the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST) group.

DNA aptamers can specifically bind to biomolecules to modify their function, potentially making them ideal oligonucleotide therapeutics. We screened the DNA aptamer melanopsin (OPN4), a blue light photopigment in the retina that plays a key role in the use of light signals to reset the phase of circadian rhythms in the central clock.

First, 15 DNA aptamers of melanopsin (Melapts) were identified following eight rounds of Cell-SELEX ...

Wars and conflicts leave devastating destruction in their wake. With so many conflicts now taking place in urban environments, scientists are studying how post-conflict peacebuilding happens in these urban settings. Dahlia Simangan, an associate professor at The IDEC Institute, Hiroshima University, has analyzed the case of Marawi, a city in the Philippines, to better understand the urban environment’s influence on post-siege reconstruction and peacebuilding. This study contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of peacebuilding by integrating conventional peacebuilding components and urban characteristics.

The findings are published ...

Osaka, Japan – From LEDs to batteries, our lives are full of electronics, and there is a constant push to make them more efficient and reliable. But as components become increasingly sophisticated, getting reliable temperature measurements of specific elements inside an object can be a challenge.

This is problematic because measuring a device’s temperature is vital for monitoring its performance or designing the materials from which it’s manufactured. Now, in a new study led by Osaka ...

High and low tide cause low and high methane fluxes

Methane, a strong greenhouse gas that naturally escapes from the bottom of the North Sea, is affected by the pressure of high or low tide. Methane emissions from the seafloor can be just easily three times as much or as little, depending on the tide. This is shown by NIOZ oceanographer Tim de Groot, in a publication in Nature Communications Earth and Environment. "Our research shows that you can never rely on one measurement when you want to know how much methane escapes from the seafloor," De Groot emphasizes.

Swamp ...

While the COVID-19 vaccines introduced many people to RNA-based medicines, RNA oligonucleotides have already been on the market for years to treat diseases like Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy and amyloidosis. RNA therapies offer many advantages over traditional small molecule drugs, including their ability to address almost any genetic component within cells and to guide gene editing tools like CRISPR to their targets.

However, the promise of RNA is currently limited by the fact that rapidly growing global demand is outpacing the industry’s ability to manufacture it. The standard method of chemically ...

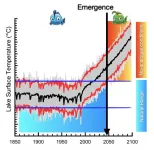

Lakes, with their rich biodiversity and important ecological services, face a concerning trend: rapidly increasing temperatures. A recent study published in Nature Geoscience by an international team of limnologists and climate modelers reveals that if current anthropogenic warming continues until the end of this century, lakes worldwide will likely experience pervasive and unprecedented surface and subsurface warming, far outside the range of what they have encountered before.

The study uses lake temperature ...

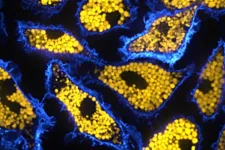

Researchers at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) have found that inflammation in an immune cell may be responsible in part for some severe symptoms in a group of rare genetic conditions called lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs).

LSDs affect about one in 7,700 live births worldwide. Children with the condition typically present at a young age with progressive neurodegeneration. Many children with LSDs die prematurely, and current treatments focus on symptom management.

Until now, the role of macrophages in the immune system and LSDs was ...

An international team of researchers led by the University of Bristol has shed light on Earth’s earliest ecosystem, showing that within a few hundred million years of planetary formation, life on Earth was already flourishing.

Everything alive today derives from a single common ancestor known affectionately as LUCA (Last Universal Common Ancestor).

LUCA is the hypothesized common ancestor from which all modern cellular life, from single celled organisms like bacteria to the gigantic redwood trees (as well as us humans) descend. LUCA represents the root ...

Astronauts on spacewalks famously have to relieve themselves inside their spacesuits. Not only is this uncomfortable for the wearer and unhygienic, it is also wasteful, as – unlike wastewater on board the International Space Station (ISS) – the water in urine from spacewalks is not recycled.

A solution for these challenges would be full-body ‘stillsuits’ like those in the blockbuster Dune franchise, which absorbed and purified water lost through sweating and urination, and recycled it into drinkable water. Now, this sci-fi ...