(Press-News.org) An ageing population will bring colossal health, social, and economic challenges over the coming decades[1]. As people live longer, staving off the physical decline and frailty that come with age has become a holy grail, with effective interventions projected to unlock significant societal and economic benefits. Estimates suggest that a slowdown in ageing that increases life expectancy by one year alone is worth US$38 trillion.[2]

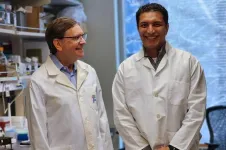

In a discovery published in Nature, a team of scientists from Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore may have found a key to slow ageing.

The team demonstrated in preclinical models that the protein interleukin-11 (IL11) actively promotes ageing and that giving an anti-IL11 therapy not only counteracts the deleterious effects of ageing but also increases lifespan. Their discovery has the potential to play a significant role in countries’ efforts to help their population live more years in good health.

IL11 leads to fat accumulation and muscle mass loss, two key hallmarks of ageing

In preclinical studies, the team found that with age, organs expressed increasing levels of the IL11 protein, which, in turn, promoted fat accumulation in the liver and abdomen, and reduced muscle mass and strength—two conditions that are hallmarks of human ageing.

According to the team, these results are the first in the world to demonstrate that IL11 is a principal factor in ageing.

First and co-corresponding author Assistant Professor Anissa Widjaja from Duke-NUS’ Cardiovascular and Metabolic Disorders Programme, said:

“This project started back in 2017 when a collaborator of ours sent us some tissue samples for another project. Out of curiosity, I ran some experiments to check for IL11 levels. From the readings, we could clearly see that the levels of IL11 increased with age and that’s when we got really excited!”

Anti-IL11 therapy counteracts effects of ageing

After establishing IL11’s role in ageing, the team demonstrated that by applying anti-IL11 therapy in the same preclinical model, metabolism was improved, shifting from generating white fat to beneficial brown fat. Brown fat breaks down blood sugar and fat molecules to help maintain body temperature and burn calories.

The researchers also observed improved muscle function and overall better health in their study, as well as an increased lifespan by up to 25 per cent in both sexes.

Unlike other drugs known to inhibit specific pathways involved in ageing, such as metformin and rapamycin, anti-IL11 therapy blocks multiple major signalling mechanisms that become dysfunctional with age, offering protection against multimorbidity from cardiometabolic diseases, age-related loss of muscle mass and strength as well as frailty.

In addition to these externally observable changes, anti-IL11 therapy also reduced the rate of telomere shortening and preserved mitochondria’s health and ability to generate energy.

Senior author Tanoto Foundation Professor of Cardiovascular Medicine at the SingHealth Duke-NUS Academic Medical Centre Stuart Cook, who is also with Duke-NUS’ Cardiovascular and Metabolic Disorders Programme, said:

“Our aim is that one day, anti-IL11 therapy will be used as widely as possible, so that people the world over can lead healthier lives for longer. However, this is not easy, as approval pathways for drugs to treat ageing are not well-defined, and raising funds to do clinical trials in this area is very challenging.”

Prof Cook is also Senior Consultant with the Department of Cardiology at the National Heart Centre Singapore.

Assessing the potential of the research, Professor Thomas Coffman, Dean of Duke-NUS, commented:

“Despite average life expectancy increasing markedly over recent decades, there’s a notable disparity between years lived and years of healthy living, free of disease. For rapidly ageing societies like Singapore’s, this discovery could be transformative, enabling older adults to prolong healthy ageing, reducing frailty and risk of falls while improving cardiometabolic health.

“This latest research is a perfect example of contributions of Duke-NUS to Singapore’s biomedical ecosystem. Across the SingHealth Duke-NUS Academic Medical Centre, our researchers and clinician-scientists conduct truly translational research, bringing discoveries from bench to bedside, benefitting people in Singapore and around the world.”

The team’s previous research on IL11’s role in the heart and kidney (published in Nature in 2017), liver (published in Gastroenterology in 2019) and lung (published in Science Translational Medicine in 2019) led to the development of an experimental anti-IL11 therapy.

In this latest work, the Duke-NUS team collaborated with scientists from the National Heart Centre Singapore; the MRC Laboratory of Medical Sciences in the UK; the Max Delbruck Centre for Molecular Medicine in Germany; and the University of Melbourne in Australia.

Duke-NUS is a leader in academic biomedical research with a mission to advance understanding of health and disease, and collaborates with clinical and industry partners to bring translational research discoveries from bench to bedside.

This research is supported by the Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council under its MOH-STaR21nov-0003 and NMRC MOH-OFIRG21nov-0006, with additional support from several other grants and philanthropic gifts.

[1] https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/Series/Analytical-Series/aging-is-the-real-population-bomb-bloom-zucker

[2] https://www.nature.com/articles/s43587-021-00080-0

END

Duke-NUS finding advances quest to slow ageing

Scientists from Duke-NUS Medical School identify interleukin-11 (IL11) as key driver of ageing, linked to increased fat accumulation and muscle loss—hallmarks of ageing. Blocking the effects of IL11 could potentially increase healthy lifespan.

2024-07-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Logged forests can still have ecological value – if not pushed too far

2024-07-17

Researchers have analysed data from 127 studies to reveal ‘thresholds’ for when logged rainforests lose the ability to sustain themselves.

The results could widen the scope of which forests are considered ‘worth’ conserving, but also show how much logging degrades forests beyond the point of no return.

The first-of-its-kind study, led by researchers from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial College London with collaborators from around the world, is published today in ...

Exoplanet caught in ‘hairpin turn’ signals how high-mass gas giants form

2024-07-17

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Astronomers have discovered a planet that has the most oblong orbit ever found among transiting planets. The exoplanet’s extreme circuit — which looks closer to a cucumber than a circle — follows one of the most drastically stretched-out orbits of all known exoplanets, planets that orbit stars outside our solar system. It is also orbiting its star backwards, lending insight into the mystery of how close-in massive gas planets, known as hot Jupiters, form, stabilize and evolve over time.

The research, led by Penn State scientists, was published today (July 17) in ...

Switching off inflammatory protein leads to longer, healthier lifespans in mice

2024-07-17

Scientists at the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Medical Science and Imperial College London have discovered that ‘switching off’ a protein called IL-11 can significantly increase the healthy lifespan of mice by almost 25%.

The scientists, working with colleagues at Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore, tested the effects of IL-11 by creating mice that had the gene producing IL-11 (interleukin 11) deleted. This extended the lives of the mice by over 20% on average.

They also treated 75-week-old mice – equivalent to the age of about 55 years in humans – with an ...

New gene therapy for muscular dystrophy offers hope

2024-07-17

A new gene therapy treatment for Duchenne muscular dystrophy shows promise of not only arresting the decline of the muscles of those affected by this inherited genetic disease, but perhaps, in the future, repairing those muscles.

The UW Medicine-led research focuses on delivering a series of protein packets inside shuttle vectors to replace the defective DMD gene within the muscles. The added genetic code will then start producing dystrophin, the protein lacking in patients with muscular dystrophy.

Currently, there is no cure for the disease ...

Scientists bridge the 'valley of death' for carbon capture technologies

2024-07-17

A major obstacle for net zero technologies in combatting climate change is bridging the gap between fundamental research and its application in the real world.

This gap, sometimes referred to as ‘the valley of death’, is common in the field of carbon capture, where novel materials are used to remove carbon dioxide from flue gasses produced by industrial processes. This prevents carbon from entering the atmosphere, helping to mitigate the effects of climate change.

Chemists have proposed and ...

Genome recording makes living cells their own historians

2024-07-17

Genomes can now be entrusted to store information about a variety of transient biological events inside of living cells, as they happen, like a flight recorder collecting data from an aircraft.

“Our method, which goes by the acronym ENGRAM, aims to turn cells into their own historians,” said Dr. Jay Shendure, a professor of genome sciences at the University of Washington School of Medicine and scientific director of the Brotman Baty Institute for Precision Medicine. Shendure led the effort, together with Wei Chen, a former graduate student, and Junhong Choi, a former postdoctoral fellow. Junhong ...

USC Schaeffer Institute launches new initiative to improve public policy through behavioral science

2024-07-17

The USC Schaeffer Institute for Public Policy & Government Service announced a new initiative today that leverages behavioral science to create more effective public policy.

The Behavioral Science & Policy Initiative at the USC Schaeffer Institute will conduct research to understand people’s beliefs and behaviors to create policies and communication that better fit people’s needs. The initiative will focus on policy topics such as climate change, health, and food insecurity.

“We want to help policymakers make a difference,” said Wändi Bruine de Bruin, the initiative’s ...

Groundwater is key to protecting global ecosystems

2024-07-17

(Santa Barbara, Calif.) — Where hidden water tables meet the Earth’s surface, life can thrive even in the driest locations. Offering refuge during times of drought, shallow groundwater aquifers act like water savings accounts that can support ecosystems with the moisture required to survive, even as precipitation dwindles. As climate change and human water use rapidly deplete groundwater levels around the world, scientists and policy makers need better data for where these groundwater-dependent ecosystems exist.

Now, a new study maps ...

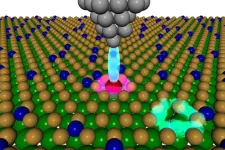

A new approach to accelerate the discovery of quantum materials

2024-07-17

– By Michael Matz

Researchers at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and several collaborating institutions have successfully demonstrated an innovative approach to find breakthrough materials for quantum applications. The approach uses rapid computing methods to predict the properties of hundreds of materials, identifying short lists of the most promising ones. Then, precise fabrication methods are used to make the short-list materials and further ...

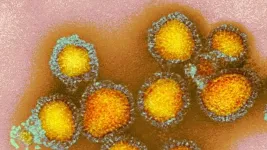

Influenza viruses can use two ways to infect cells

2024-07-17

Most influenza viruses enter human or animal cells through specific pathways on the cells’ surface. Researchers at the University of Zurich have now discovered that certain human flu viruses and avian flu viruses can also use a second entry pathway, a protein complex of the immune system, to infect cells. This ability helps the viruses infect different species – and potentially jump between animals and humans.

The majority of type A influenza viruses circulating in birds and pigs aren’t normally a health ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

Greaux Healthy Day declared in Lake Charles: Pennington Biomedical’s Greaux Healthy Initiative highlights childhood obesity challenge in SWLA

Into the heart of a dynamical neutron star

The weight of stress: Helping parents may protect children from obesity

Cost of physical therapy varies widely from state-to-state

Material previously thought to be quantum is actually new, nonquantum state of matter

Employment of people with disabilities declines in february

Peter WT Pisters, MD, honored with Charles M. Balch, MD, Distinguished Service Award from Society of Surgical Oncology

Rare pancreatic tumor case suggests distinctive calcification patterns in solid pseudopapillary neoplasms

Tubulin prevents toxic protein clumps in the brain, fighting back neurodegeneration

Less trippy, more therapeutic ‘magic mushrooms’

Concrete as a carbon sink

[Press-News.org] Duke-NUS finding advances quest to slow ageingScientists from Duke-NUS Medical School identify interleukin-11 (IL11) as key driver of ageing, linked to increased fat accumulation and muscle loss—hallmarks of ageing. Blocking the effects of IL11 could potentially increase healthy lifespan.