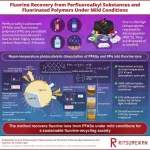

Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs), nicknamed ‘forever chemicals,’ pose a growing environmental and health threat. Since the invention of Teflon in 1938, PFASs and perfluorinated polymers or PFs have been widely used for their exceptional stability and resistance to water and heat. These properties made them ideal for countless applications, from cookware and clothing to firefighting foam. However, this very stability has become a major problem. PFASs do not easily break down in the environment, leading to their accumulation in water, soil, and even the bodies of humans, where they are known to cause carcinogenic effects and hormonal disruptions. Today, these chemicals can be found in drinking water supplies, food, and even in the soil of Antarctica. Although there are plans to phase out PFAS production, treating them remains challenging as they decompose only at temperatures exceeding 400 °C. As a result, certain amounts of products containing PFASs and PFs end up in landfills, potentially creating future contamination risks.

Now, a room-temperature defluorination method proposed by researchers at Ritsumeikan University could revolutionize PFAS treatment. Their study, published in the journal Angewandte Chemie International Edition on 19 June 2024, details a photocatalytic method that uses visible light to break down PFAS and other fluorinated polymers (FPs) at room temperature into fluorine ions. Using this method, the researchers achieved 100% defluorination of perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) within just 8 hours of light exposure.

“The proposed methodology is promising for the effective decomposition of diverse perfluoroalkyl substances under gentle conditions, thereby significantly contributing towards the establishment of a sustainable fluorine-recycling society,” says Professor Yoichi Kobayashi, the lead author of the study.

The proposed method involves irradiating visible LED light onto cadmium sulfide (CdS) nanocrystals and copper-doped CdS (Cu-CdS) nanocrystals with surface ligands of mercaptopropionic acid (MPA) in a solution containing PFAS, FPs, and triethanolamine (TEOA). The researchers found that irradiating these semiconductor nanocrystals generates electrons with a high reduction potential that break down the strong carbon-fluorine bonds in PFAS molecules.

For the photocatalytic reaction, the researchers added 0.8 mg of CdS nanocrystals (NCs), 0.65 mg of PFOS, and 20 mg of TEOA to 1.0 ml of water. They then exposed the solution to 405-nanometer LED light to initiate the photocatalytic reaction. This light excites the nanoparticles, generating electron-hole pairs and promoting the removal of MPA ligands from the surface of the nanocrystals, creating space for PFOS molecules to adsorb onto the NC surface.

To prevent photoexcited electrons from recombining with holes, TEOA is added to capture the holes and prolong the lifetime of the reactive electrons available for PFAS decomposition. These electrons undergo an Auger recombination process, where one exciton (an electron-hole pair) recombines non-radiatively, transferring its energy to another electron, and creating highly excited electrons. These highly excited electrons possess enough energy to participate in chemical reactions with the PFOS molecules adsorbed on the NC surface. The reactions lead to the breaking of carbon-fluorine (C-F) bonds in PFOS, resulting in the removal of fluorine ions from the PFAS molecules.

The presence of hydrated electrons, generated by Auger recombination, was confirmed by laser flash photolysis measurements, which identified transient species based on the absorption spectrum upon laser pulse excitation. The defluorination efficiency depended on the amount of NCs and TEOA used in the reaction and increased with the period of light exposure. For PFOS, the efficiency of defluorination was 55%, 70–80%, and 100% for 1-, 2-, and 8-hour light irradiation, respectively. Using this method, the researchers also successfully achieved 81% defluorination of Nafion, a fluoropolymer, after 24 hours of light irradiation. Nafion is widely used as an ion-exchange membrane in electrolysis and batteries.

Fluorine is a critical component in many industries, from pharmaceuticals to clean energy technologies. By recovering fluorine from waste PFAS, we can reduce reliance on fluorine production and establish a more sustainable recycling process. “This technique will contribute to the development of recycling technologies for fluorine elements, which are used in various industries and support our prosperous society,” concludes Prof. Kobayashi.

***

Reference

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202408687

About Ritsumeikan University, Japan

Ritsumeikan University is one of the most prestigious private universities in Japan. Its main campus is in Kyoto, where inspiring settings await researchers. With an unwavering objective to generate social symbiotic values and emergent talents, it aims to emerge as a next-generation research university. It will enhance researcher potential by providing support best suited to the needs of young and leading researchers, according to their career stage. Ritsumeikan University also endeavors to build a global research network as a “knowledge node” and disseminate achievements internationally, thereby contributing to the resolution of social/humanistic issues through interdisciplinary research and social implementation.

Website: http://en.ritsumei.ac.jp/

Ritsumeikan University Research Report: https://www.ritsumei.ac.jp/research/radiant/eng/

About Professor Yoichi Kobayashi from Ritsumeikan University, Japan

Dr. Yoichi Kobayashi is a Professor in the Department of Applied Chemistry in Ritsumeikan University, Japan, and a Ritsumeikan Advanced Research Academy (RARA) Associate Fellow. Dr. Kobayashi graduated from Kwansei Gakuin University, Japan, in 2007, from where he also obtained his PhD in 2011. Before joining Ritsumeikan University, he worked for the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science at the University of Toronto, Canada, and Aoyama Gakuin University for several years. He now leads a research group in the Photofunctional Physical Chemistry Lab, where they conduct cutting-edge studies on photochromism, optical nanostructures and nanoparticles, photophysics, and photochemistry. He has published over 80 peer-reviewed papers.

Funding information

This work was supported by JST, PRESTO Grant Numbers JPMJPR22N6, JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP21K05012, JP24K01460, and Advanced Research Infrastructure for Materials and Nanotechnology, The Ultramicroscopy Research Center, Kyushu University (JPMXP1223KU0055)

END