A team of scientists from Montana State University has provided the first experimental evidence that two new groups of microbes thriving in thermal features in Yellowstone National Park produce methane – a discovery that could one day contribute to the development of methods to mitigate climate change and provide insight into potential life elsewhere in our solar system.

The journal Nature this week published the findings from the laboratory of Roland Hatzenpichler, associate professor in MSU’s Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry in the College of Letters and Science and associate director of the university’s Thermal Biology Institute. The two scientific papers describe the MSU researchers’ verification of the first known examples of single-celled organisms that produce methane to exist outside the lineage Euryarchaeota, which is part of the larger branch of the tree of life called Archaea.

Alison Harmon, MSU’s vice president for research and economic development, said she is excited that the findings with such far-reaching potential impact are receiving the attention they deserve.

“It’s a significant achievement for Montana State University to have not one but two papers published in one of the world’s leading scientific journals,” Harmon said.

The methane-producing single-celled organisms are called methanogens. While humans and other animals eat food, breathe oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide to survive, methanogens eat small molecules like carbon dioxide or methanol and exhale methane. Most methanogens are strict anaerobes, meaning they cannot survive in the presence of oxygen.

Scientists have known since the 1930s that many anaerobic organisms within the archaea are methanogens, and for decades they believed that all methanogens were in a single phylum: the Euryarchaeota.

But about 10 years ago, microbes with genes for methanogenesis began to be discovered in other phyla, including one called Thermoproteota. That phylum contains two microbial groups called Methanomethylicia and Methanodesulfokora.

“All we knew about these organisms was their DNA,” Hatzenpichler said. “No one had ever seen a cell of these supposed methanogens; no one knew if they actually used their methanogenesis genes or if they were growing by some other means.

Hatzenpichler and his researchers set out to test whether the organisms were living by methanogenesis, basing their work on the results of a study published last year by one of his former graduate students at MSU, Mackenzie Lynes.

Samples were harvested from sediments in Yellowstone National Park hot springs ranging in temperature from 141 to 161 degrees Fahrenheit (61–72 degrees Celsius).

Through what Hatzenpichler described as “painstaking work,” MSU doctoral student Anthony Kohtz and postdoctoral researcher Viola Krukenberg grew the Yellowstone microbes in the lab. The microbes not only survived but thrived – and they produced methane. The team then worked to characterize the biology of the new microbes, involving staff scientist Zackary Jay and others at ETH Zurich.

At the same time, a research group led by Lei Cheng from China’s Biogas Institute of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs and Diana Sousa from Wageningen University in the Netherlands successfully grew another one of these novel methanogens, a project they had worked on for six years.

“Until our studies, no experimental work had been done on these microbes, aside from DNA sequencing,” said Hatzenpichler.

He said Cheng and Sousa offered to submit the studies together for publication, and Cheng’s paperreporting the isolation of another member of Methanomethylicia was published jointly with the two Hatzenpichler lab studies.

While one of the newly identified group of methanogens, Methanodesulfokora, seems to be confined to hot springs and deep-sea hydrothermal vents, Methanomethylicia, are widespread, Hatzenpichler said. They are sometimes found in wastewater treatment plants and the digestive tracts of ruminant animals, and in marine sediments, soils and wetlands. Hatzenpichler said that’s significant because methanogens produce 70% of the world’s methane, a gas 28 times more potent than carbon dioxide in trapping heat in the atmosphere, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

“Methane levels are increasing at a much higher rate than carbon dioxide, and humans are pumping methane at a higher rate into the atmosphere than ever before,” he said.

Hatzenpichler said that while the experiments answered an important question, they generated many more that will fuel future work. For example, scientists don’t yet know whether Methanomethylicia that live in non-extreme environments rely on methanogenesis to grow or if they grow by other means.

“My best bet is that they sometimes grow by making methane, and sometimes they do something else entirely, but we don’t know when they grow, or how, or why.” Hatzenpichler said. “We now need to find out when they contribute to methane cycling and when not.”

Whereas most methanogens within the Euryarchaeota use CO2 or acetate to make methane, Methanomethylicia and Methanodesulfokora use compounds such as methanol. This property could help scientists learn how to alter conditions in the different environments where they are found so that less methane is emitted into the atmosphere, Hatzenpichler said.

His lab will begin collaborating this fall with MSU’s Bozeman Agricultural Research and Teaching Farm, which will provide samples for further research into the methanogens found in cattle. In addition, new graduate students joining Hatzenpichler’s lab in the fall will determine whether the newly found archaea produce methane in wastewater, soils and wetlands.

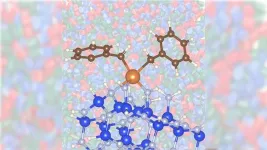

Methanomethylicia also have a fascinating cell architecture, Hatzenpichler said. He collaborated with two scientists at ETH Zurich, Martin Pilhofer and graduate student Nickolai Petrosian, to show that the microbe forms previously unknown cell-to-cell tubes that connect two or three cells with each other.

“We have no idea why they are forming them. Structures like these have rarely been seen in microbes. Maybe they exchange DNA; maybe they exchange chemicals. We don't know yet,” said Hatzenpichler.

The newly published research was funded by NASA’s exobiology program. NASA is interested in methanogens because they may give insights into life on Earth more than 3 billion years ago and the potential for life on other planets and moons where methane has been detected, he said.

Hatzenpichler has discussed the results of the two studies in an online lecture and on a recent Matters Microbial podcast, and produced this infographic on methane cycling. To learn more about his lab visit www.environmental-microbiology.com or send an email to roland.hatzenpichler@montana.edu.

END