(Press-News.org) In humans and other animals, signals from a central circadian clock in the brain generate the seasonal and daily rhythms of life. They help the body to prepare for expected changes in the environment and also optimize when to sleep, eat and do other daily activities.

Scientists at Washington University in St. Louis are working out the particulars of how our internal biological clocks keep time. Their new research, published July 24 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, helps answer longstanding questions about how circadian rhythms are generated and maintained.

In all mammals, the signals for circadian rhythms come from a small part of the brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus, or SCN. Several previous studies from WashU and other institutions have attempted to determine if a neurotransmitter called GABA plays a role in synchronizing circadian rhythms among individual SCN neurons. However, the role of GABA in the SCN had remained unclear.

“In the past, we have published data on pharmacological blocking of the GABA system and found only modest increases in synchrony among SCN cells,” said Daniel Granados-Fuentes, a research scientist in Arts & Sciences and first author of the new study.

The chemical interventions that he and other scientists introduced didn’t seem to change the way that neurons in the SCN fired that much, or to affect circadian regulation of actual behavior in mice, either.

So Granados-Fuentes and his team members took a different approach. The researchers changed the expression of two kinds of GABA receptors to figure out if receptor density had any impact on synchrony or behavior.

“Tuning the number of receptors is considered to be important to regulate physiological processes like learning and memory, but not circadian rhythms,” Granados-Fuentes said. But in this case, changing the density of either γ2 or δ GABA receptors had a dramatic effect.

Reducing or mutating these receptors in the SCN of mice decreased the amplitude of their circadian rhythms to one-third. The mice in this study increased their daytime wheel-running and reduced their normal nocturnal running.

The researchers also found that reduction or mutation of either γ2 or δ GABA receptors halved the synchrony among, and amplitude of, circadian SCN cells as measured by firing rate or protein expression in vitro.

Overexpression of either of two GABA receptor types compensated for the loss of the other, suggesting that these two receptors can function in a similar way in the SCN, even though they have been described to mediate different physiological processes, Granados-Fuentes said.

Understanding circadian rhythms is important because people can suffer many negative consequences if these rhythms get disrupted. They can experience daytime fatigue, changes in hormone profiles, gastrointestinal issues, changes in mood and more.

“These findings open a possibility to understand if changes in the density of GABA receptors are important to regulate seasonal responses, for example how animals in nature respond to summer when days are long or winter when days are short,” Granados-Fuentes said.

Granados-Fuentes works in the laboratory of biologist Erik Herzog, the Viktor Hamburger Distinguished Professor in Arts & Sciences and a co-author of this study. Steven Mennerick, the John P. Feighner Professor of Neuropsychopharmacology at Washington University School of Medicine and a professor of psychiatry and of neuroscience, is a collaborator and co-author.

This research helped lead to a new grant from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), for the Herzog laboratory with collaborators in WashU’s McKelvey School of Engineering and at Saint Louis University.

Research reported in this publication was supported by a grant from the NINDS (RO1NS121161). The study authors also thank the Taylor Family Institute for Innovative Psychiatric Research for support.

END

Daily rhythms depend on receptor density in biological clock

2024-07-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New England Journal of Medicine publishes outcomes from practice-changing E1910 trial for patients with BCR::ABL1-negative B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia

2024-07-24

A significant survival improvement for adults with newly diagnosed BCR::ABL1-negative B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia is published today by the New England Journal of Medicine. The practice-changing finding is from the randomized phase 3 study E1910 (NCT02003222), which evaluated blinatumomab immunotherapy in patients who were in remission and tested negative for measurable residual disease (MRD) after an initial round of chemotherapy. At 3 years of follow-up, 85% of the patients who went on to receive additional standard consolidation chemotherapy plus experimental blinatumomab were alive, compared to 68% of those who received chemotherapy only.

Blinatumomab (Blincyto, ...

Older adults want to cut back on medication, but study shows need for caution

2024-07-24

More than 82% of Americans age 50 to 80 take one or more kinds of prescription medication, and 80% of them say they’d be open to stopping one or more of those drugs if their health care provider gave the green light, a new University of Michigan study shows.

But it’s not as simple as that, the researchers say. They call for prescribers and pharmacists to talk with older adults about their personal situation and figure out if any kind of “deprescribing” is right for them.

The study, published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, uses data from U-M’s National Poll on Healthy Aging, and builds on a poll report issued in April 2023.

It ...

Nationwide flood models poorly capture risks to households and properties

2024-07-24

Irvine, Calif., July 24, 2024 – Government agencies, insurance companies and disaster planners rely on national flood risk models from the private sector that aren’t reliable at smaller levels such as neighborhoods and individual properties, according to researchers at the University of California, Irvine.

In a paper published recently in the American Geophysical Union journal Earth’s Future, experts in UC Irvine’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering caution that relatively new, nation-scale flood data provides an inadequate representation of local topography and infrastructure, factors known to control the spread of floods ...

Does your body composition affect your risk of dementia or Parkinson’s?

2024-07-24

MINNEAPOLIS – People with high levels of body fat stored in their belly or arms may be more likely to develop diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s than people with low levels of fat in these areas, according to a study published in the July 24, 2024, online issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology. The study also found that people with a high level of muscle strength were less likely to develop these diseases than people with low muscle strength.

“These neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s affect over 60 million people worldwide, and that number is expected ...

Researchers discover faster, more energy-efficient way to manufacture an industrially important chemical

2024-07-24

Polypropylene is a common type of plastic found in many essential products used today, such as food containers and medical devices. Because polypropylene is so popular, demand is surging for a chemical used to make it. That chemical, propylene, can be produced from propane. Propane is a natural gas commonly used in barbeque grills.

Scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory and Ames National Laboratory report a faster, more energy-efficient way to manufacture propylene than the process currently used.

Converting propane into propylene ...

AI model identifies certain breast tumor stages likely to progress to invasive cancer

2024-07-24

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is a type of preinvasive tumor that sometimes progresses to a highly deadly form of breast cancer. It accounts for about 25 percent of all breast cancer diagnoses.

Because it is difficult for clinicians to determine the type and stage of DCIS, patients with DCIS are often overtreated. To address this, an interdisciplinary team of researchers from MIT and ETH Zurich developed an AI model that can identify the different stages of DCIS from a cheap and easy-to-obtain breast tissue image. Their model shows that both the state and arrangement ...

Researchers are closing in on a mouse model for late-onset Alzheimer’s

2024-07-24

Mice don’t get Alzheimer’s—and while that’s good news for mice, it’s a big problem for biomedical researchers seeking to understand the disease and test new treatments. Now, researchers at The Jackson Laboratory are working to create the first strain of mice that’s genetically susceptible to late-onset Alzheimer’s, with potentially transformative implications for dementia research.

In humans, two of the defining traits of Alzheimer’s disease are amyloid plaques between brain cells, and tangles of tau proteins within neurons. In mice, however, intercellular ...

New analysis offers most comprehensive roadmap to date for more targeted Alzheimer’s research and drug discovery

2024-07-24

From studying the human genome, to analyzing the way proteins are encoded, or monitoring RNA expression, researchers are rapidly gaining a far richer understanding of the complex genetic and cellular mechanisms that underpin dementia. But there’s a catch: While new technologies are revealing myriad avenues for Alzheimer’s research, it’s impossible to know in advance which research pathways will lead to effective treatments.

“We have countless potential targets, but we don’t know which ones to aim at,” said Greg Carter, the Bernard and Lusia Milch Endowed Chair at the ...

Hens blush when they are scared or excited

2024-07-24

Hens fluff their head feathers and blush to express different emotions and levels of excitement, according to a study publishing July 24, 2024, in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Cécile Arnould and colleagues from INRAE and CNRS, France.

Facial expressions are an important part of human communication that allow us to convey our emotions. Scientists have found similar signals of emotion in other mammals such as dogs, pigs and mice. Although birds can produce facial expressions by moving their head feathers and flushing their skin, it is unclear whether they express emotions in this way. To investigate, researchers filmed ...

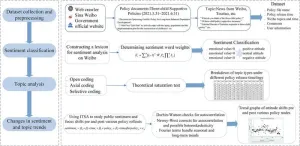

Weibo posts illuminate public response to China’s three-child policy measures

2024-07-24

An analysis of comments on Chinese social media platform Sina Weibo reveals trends in the public response to measures implemented to support China’s three-child policy, highlighting concerns about women’s rights and employment. Lijuan Peng of Zhejiang Gongshang University in Hangzhou, China, and colleagues present these findings in the open-access journal PLOS ONE on July 24, 2024.

For decades, China’s one-child policy restricted most families to having just one child. In 2021, to combat a falling birthrate, China introduced its three-child policy, allowing couples to have up to three children. To help encourage childbirth, ...