(Press-News.org) MINNEAPOLIS / ST. PAUL (07/25/2024) — Engineering researchers at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities have demonstrated a state-of-the-art hardware device that could reduce energy consumption for artificial intelligent (AI) computing applications by a factor of at least 1,000.

The research is published in npj Unconventional Computing, a peer-reviewed scientific journal published by Nature. The researchers have multiple patents on the technology used in the device.

With the growing demand of AI applications, researchers have been looking at ways to create a more energy efficient process, while keeping performance high and costs low. Commonly, machine or artificial intelligence processes transfer data between both logic (where information is processed within a system) and memory (where the data is stored), consuming a large amount of power and energy.

A team of researchers in the University of Minnesota College of Science and Engineering demonstrated a new model where the data never leaves the memory, called computational random-access memory (CRAM).

“This work is the first experimental demonstration of CRAM, where the data can be processed entirely within the memory array without the need to leave the grid where a computer stores information,” said Yang Lv, a University of Minnesota Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering postdoctoral researcher and first author of the paper.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) issued a global energy use forecast in March of 2024, forecasting that energy consumption for AI is likely to double from 460 terawatt-hours (TWh) in 2022 to 1,000 TWh in 2026. This is roughly equivalent to the electricity consumption of the entire country of Japan.

According to the new paper’s authors, a CRAM-based machine learning inference accelerator is estimated to achieve an improvement on the order of 1,000. Another example showed an energy savings of 2,500 and 1,700 times compared to traditional methods.

This research has been more than two decades in the making,

“Our initial concept to use memory cells directly for computing 20 years ago was considered crazy” said Jian-Ping Wang, the senior author on the paper and a Distinguished McKnight Professor and Robert F. Hartmann Chair in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the University of Minnesota.

“With an evolving group of students since 2003 and a true interdisciplinary faculty team built at the University of Minnesota—from physics, materials science and engineering, computer science and engineering, to modeling and benchmarking, and hardware creation—we were able to obtain positive results and now have demonstrated that this kind of technology is feasible and is ready to be incorporated into technology,” Wang said.

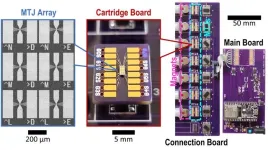

This research is part of a coherent and long-standing effort building upon Wang’s and his collaborators’ groundbreaking, patented research into Magnetic Tunnel Junctions (MTJs) devices, which are nanostructured devices used to improve hard drives, sensors, and other microelectronics systems, including Magnetic Random Access Memory (MRAM), which has been used in embedded systems such as microcontrollers and smart watches.

The CRAM architecture enables the true computation in and by memory and breaks down the wall between the computation and memory as the bottleneck in traditional von Neumann architecture, a theoretical design for a stored program computer that serves as the basis for almost all modern computers.

“As an extremely energy-efficient digital based in-memory computing substrate, CRAM is very flexible in that computation can be performed in any location in the memory array. Accordingly, we can reconfigure CRAM to best match the performance needs of a diverse set of AI algorithms,” said Ulya Karpuzcu, an expert on computing architecture, co-author on the paper, and Associate Professor in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the University of Minnesota. “It is more energy-efficient than traditional building blocks for today’s AI systems.”

CRAM performs computations directly within memory cells, utilizing the array structure efficiently, which eliminates the need for slow and energy-intensive data transfers, Karpuzcu explained.

The most efficient short-term random access memory, or RAM, device uses four or five transistors to code a one or a zero but one MTJ, a spintronic device, can perform the same function at a fraction of the energy, with higher speed, and is resilient to harsh environments. Spintronic devices leverage the spin of electrons rather than the electrical charge to store data, providing a more efficient alternative to traditional transistor-based chips.

Currently, the team has been planning to work with semiconductor industry leaders, including those in Minnesota, to provide large scale demonstrations and produce the hardware to advance AI functionality.

In addition to Lv, Wang, and Karpuzcu, the team included University of Minnesota Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering researchers Robert Bloom and Husrev Cilasun; Distinguished McKnight Professor and Robert and Marjorie Henle Chair Sachin Sapatnekar; and former postdoctoral researchers Brandon Zink, Zamshed Chowdhury, and Salonik Resch; along with researchers from Arizona University: Pravin Khanal, Ali Habiboglu, and Professor Weigang Wang

This work was supported by grants from the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the National Science Foundation (NSF), and Cisco Inc. Research including nanodevice patterning was conducted in collaboration with the Minnesota Nano Center and simulation/calculation work was done with the Minnesota Supercomputing Institute at the University of Minnesota.

To read the entire research paper entitled, “Experimental demonstration of magnetic tunnel junction-based computational random-access memory,” visit the npj Unconventional Computing website.

END

Researchers develop state-of-the-art device to make artificial intelligence more energy efficient

Energy consumption from artificial intelligence could be reduced by a factor of at least 1,000 with this device

2024-07-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

The Texas Heart Institute provides BiVACOR® Total Artificial Heart Patient update

2024-07-26

Houston, Texas, July 26, 2024 – The Texas Heart Institute (THI), a globally renowned cardiovascular health center, and BiVACOR®, a leading clinical-stage medical device company, are pleased to provide an update on the condition of the first patient to receive the BiVACOR Total Artificial Heart (TAH) implant on July 9, as part of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Early Feasibility Study (EFS). On July 17, eight days following the BiVACOR TAH implant, a donor heart became available and was transplanted into the ...

The ancestor of all modern birds probably had iridescent feathers

2024-07-26

The color palette of the birds you see out your window depend on where you live. If you’re far from the Equator, most birds tend to have drab colors, but the closer you are to the tropics, you’ll probably see more and more colorful feathers. Scientists have long been puzzled about why there are more brilliantly-colored birds in the tropics than in other places, and they’ve also wondered how those brightly-colored birds got there in the first place: that is, if those colorful feathers evolved in the tropics, or if tropical birds have colorful ancestors that came to the region from somewhere else. In a new study published ...

A rare form of ice at the center of a cool new discovery about how water droplets freeze

2024-07-26

Tokyo, Japan – Ice is far more complicated than most of us realize, with over 20 different varieties known to science, forming under various combinations of pressure and temperature. The kind we use to chill our drinks is known as ice I, and it’s one of the few forms of ice that exist naturally on Earth. Researchers from Japan have recently discovered another type of ice: ice 0, an unusual form of ice that can seed the formation of ice crystals in supercooled water.

The formation of ice near the surface ...

Embargoed - Researchers devise novel solution to preventing relapse after CAR T-cell therapy

2024-07-26

Lack of persistence of CAR T cells is major limiting step in CAR T-cell therapy

Made by fusing an immune-stimulatory molecule to a protein from cancer cells, the therapy selectively targets CAR T cells and enhances their functionality and persistence in the body, extending their attack on cancer.

The therapy, called CAR-Enhancer (CAR-E), also causes CAR T cells to retain a memory of the cancer, allowing them to mount another attack if cancer recurs

BOSTON – Even as they have revolutionized the treatment of certain forms of cancer, CAR T-cell therapies ...

Lampreys possess a ‘jaw-dropping’ evolutionary origin

2024-07-26

EVANSTON, Ill. --- One of just two vertebrates without a jaw, sea lampreys that are wreaking havoc in Midwestern fisheries are simultaneously helping scientists understand the origins of two important stem cells that drove the evolution of vertebrates.

Northwestern University biologists have pinpointed when the gene network that regulates these stem cells may have evolved and gained insights into what might be responsible for lampreys’ missing mandibles.

The two cell types — pluripotent blastula cells (or embryonic stem cells) and neural crest cells — are both “pluripotent,” ...

"Just like your mother?" Maternal and paternal X-chromosomes show skewed distribution in different organs and tissues.

2024-07-26

A new study published in Nature Genetics by the Lymphoid Development Group at the MRC Laboratory of Medical Sciences has reveals that the contribution of cells expressing maternal or paternal X chromosomes can be selectively skewed in different parts of the body. The study leverages human data from the 1000 Genomes Project combined with mouse models of human X chromosome-linked DNA sequence variation to advance our fundamental understanding of development in biologically female individuals who have two X chromosomes.

Until now, it was thought that the usage of maternal and paternal X-chromosomes was similar throughout the body. The ...

Conflicting health advice from agencies drives confusion, study finds, but doctors remain most trusted

2024-07-26

Distrust of health experts and credulity towards misinformation can kill. For example, during the Covid-19 crisis, high-profile health experts received death threats while misinformation went viral on social media. And already long before the pandemic, easily preventable but potentially serious diseases had been making a comeback around the world due to vaccine hesitancy – often powered by conspiracy theories.

But what feeds this lack in trust in reliable sources of health information? Can it perhaps be mitigated? Those are the subjects of a new study in Frontiers in Medicine by researchers from the US.

“Here we show that individuals who ...

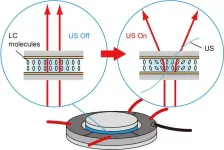

Towards next-gen indoor lighting: novel tunable ultrasonic liquid crystal light diffuser

2024-07-26

It is no mystery that light is essential to human life. Since the discovery of fire, humans have developed various artificial light sources, such as incandescent lamps, gaslights, discharge lamps, and light-emitting diodes (LEDs). The distribution and intensity of artificial lights indoors are important factors that affect our ability to study and work effectively and influence our physical and mental health. Consequently, modern artificial light sources are designed with these psychological elements to achieve the best aesthetics. ...

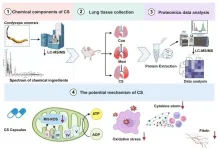

Chinese medicinal fungus shows promise in treating idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

2024-07-26

A recent study from China has reported that Cordyceps sinensis (CS), a traditional Chinese medicinal fungus, can ameliorate idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) in mice by inhibiting mitochondrion-mediated oxidative stress. The research, conducted by a team led by Huan Tang and Jigang Wang from the Institute of Chinese Materia Medica at the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, was published in Wiley's MedComm-Future Medicine.

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is a chronic and progressive lung disease characterized by a decline in lung function, ultimately leading to respiratory failure and a significantly reduced quality of life for patients. With a median ...

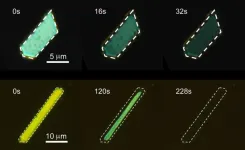

Shining light on similar crystals reveals photoreactions can differ

2024-07-26

A rose by any other name is a rose, but what of a crystal? Osaka Metropolitan University-led researchers have found that single crystals of four anthracene derivatives with different substituents react differently when irradiated with light, perhaps holding clues to how we can use such materials in functional ways.

Graduate student Sogo Kataoka, Dr. Daichi Kitagawa, a lecturer, and Professor Seiya Kobatake of the Graduate School of Engineering and colleagues compared the photoreactions of the single crystals when the entire anthracene crystal was irradiated with light.

For two ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

A clinical reveals that aniridia causes a progressive loss of corneal sensitivity

Fossil amber reveals the secret lives of Cretaceous ants

Predicting extreme rainfall through novel spatial modeling

The Lancet: First-ever in-utero stem cell therapy for fetal spina bifida repair is safe, study finds

Nanoplastics can interact with Salmonella to affect food safety, study shows

Eric Moore, M.D., elected to Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees

NYU named “research powerhouse” in new analysis

New polymer materials may offer breakthrough solution for hard-to-remove PFAS in water

Biochar can either curb or boost greenhouse gas emissions depending on soil conditions, new study finds

Nanobiochar emerges as a next generation solution for cleaner water, healthier soils, and resilient ecosystems

Study finds more parents saying ‘No’ to vitamin K, putting babies’ brains at risk

Scientists develop new gut health measure that tracks disease

Rice gene discovery could cut fertiliser use while protecting yields

Jumping ‘DNA parasites’ linked to early stages of tumour formation

Ultra-sensitive CAR T cells provide potential strategy to treat solid tumors

Early Neanderthal-Human interbreeding was strongly sex biased

North American bird declines are widespread and accelerating in agricultural hotspots

Researchers recommend strategies for improved genetic privacy legislation

How birds achieve sweet success

More sensitive cell therapy may be a HIT against solid cancers

Scientists map how aging reshapes cells across the entire mammalian body

Hotspots of accelerated bird decline linked to agricultural activity

How ancient attraction shaped the human genome

NJIT faculty named Senior Members of the National Academy of Inventors

App aids substance use recovery in vulnerable populations

College students nationwide received lifesaving education on sudden cardiac death

[Press-News.org] Researchers develop state-of-the-art device to make artificial intelligence more energy efficientEnergy consumption from artificial intelligence could be reduced by a factor of at least 1,000 with this device