(Press-News.org) For some forms of tuberculosis, the chances that an exposed person will get infected depend on whether the individual and the bacteria share a hometown, according to a new study comparing how different strains move through mixed populations in cosmopolitan cities.

Results of the research, led by Harvard Medical School scientists and published Aug. 1 in Nature Microbiology, provide the first hard evidence of long-standing observations that have led scientists to suspect that pathogen, place, and human host collide in a distinctive interplay that influences infection risk and fuels differences in susceptibility to infection.

The study strengthens the case for a long-standing hypothesis in the field that specific bacteria and their human hosts likely coevolved over hundreds or thousands of years, the researchers said.

The findings may also help inform new prevention and treatment approaches for tuberculosis, a wily pathogen that, each year, sickens more than 10 million people and causes more than a million deaths worldwide, according to the World Health Organization.

In the current analysis, believed to be the first controlled comparison of TB strains’ infectivity in populations of mixed geographic origins, the researchers custom built a study cohort by combining case files from patients with TB in New York City, Amsterdam, and Hamburg. Doing so gave them enough data to power their models.

The analysis showed that close household contacts of people diagnosed with a strain of TB from a geographically restricted lineage had a 14 percent lower rate of infection and a 45 percent lower rate of developing active TB disease compared with those exposed to a strain belonging to a widespread lineage.

The study also showed that strains with narrow geographic ranges are much more likely to infect people with roots in the bacteria’s native geographic region than people from outside the region.

The researchers found that the odds of infection dropped by 38 percent when a contact is exposed to a restricted pathogen from a geographic region that doesn’t match the person’s background, compared with when a person is exposed to a geographically restricted microbe from a region that does match their home country. This was true for people who had lived in the region themselves and for people whose two parents could each trace their heritage to the region.

This pathogen-host affinity points to a shared evolution between humans and microbes with certain biological features rendering both more compatible and fueling the risk for infection, the researchers said.

“The size of the effect is surprisingly large,” said Maha Farhat, the Gilbert S. Omenn, MD ’65, PhD Associate Professor of Biomedical Informatics in the Blavatnik Institute at HMS. “That’s a good indicator that the impact on public health is substantial.”

Why differences matter

Thanks to the growing use of genetic sequencing, researchers have observed not all circulating strains are created equal. Some lineages are widespread and responsible for much of the TB around the world, while others are prevalent only in a few restricted areas. Given that the complex nature of TB transmission in high-incidence settings where people often have multiple exposures to different lineages, researchers have not been able to compare strains under similar conditions and have been left to speculate about possible explanations for the differences between strains.

Many factors increase the risk of contracting tuberculosis from a close contact. One of the best predictors of whether a person will infect their close contacts is bacterial load, measured by a test called sputum smear microscopy, which shows how many bacteria a person carries in their respiratory system.

But the new study showed that for geographically restricted strains, whether a person has ancestors who lived where the strain is common was an even bigger predictor of infection risk than bacterial load in the sputum. In the cases analyzed in the study, this risk of common ancestry even outweighed the risk stemming from having diabetes and other chronic diseases previously shown to render people more susceptible to infection.

The findings add to a growing body of evidence of the importance of paying attention to the wide variation between different lineages of tuberculosis and to the details of how different lineages of tuberculosis interact with different host populations.

Previous studies have shown that some genetic groups of TB are more prone to developing drug resistance and that TB vaccines appear to work better in some places than others. There is also evidence that some treatment regimens might be better suited to some strains of TB than others.

“These findings emphasize how important it is to understand what makes different strains of TB behave so differently from one another, and why some strains have such a close affinity for specific, related groups of people,” said Matthias Groeschel, research fellow in biomedical informatics in Farhat’s lab at HMS; resident physician at Charité, a university hospital in Berlin; and the study’s first author.

In addition to the analysis of clinical, genomic, and public health data, the researchers also tested the ability of different strains of TB to infect human macrophages, a type of immune cell that TB hijacks to cause infection and disease. The researchers grew cells from donors from different regions. Once again, cell lines from people with ancestry that matched the native habitat of a restricted strain of tuberculosis bacteria were more susceptible to the germs than cells from people from outside the area, mirroring the results of their epidemiologic study.

Until now, most experiments of the interaction between human immune cells and TB have not compared how TB interacts with cells of hosts from different populations or places, the researchers said.

While this experiment was not designed to capture insights about the mechanism underlying the affinity between human and TB populations sharing geographic backgrounds, it highlights the importance of using multiple strains of TB and cells from diverse populations to inform treatment and prevention. It also points to the need for more basic research to understand the genomic and structural differences in how bacterial and host cells interface, the researchers said.

“It's so important to appreciate that the great diversity of human and tuberculosis genetics can significantly impact how people and microbes respond to one another and to things like drugs and vaccines,” Farhat said. “We have to incorporate that into the way we think about the disease.”

“We’re at the very beginning of appreciating the importance of that diversity,” Groeschel said. “There’s so much more to learn about how it might impact the efficacy of drugs, vaccines, and the course that disease takes in different strains.”

Advances in gene sequencing create a new puzzle

While the closely related but distinct genetic groups of tuberculosis were discovered with more traditional methods of genotyping, the widespread use of whole genome sequencing by public health departments around the world allowed doctors and researchers to better profile TB germs and track outbreaks and drug resistance genetically.

The realization that highly localized stains didn’t spread well to other regions led researchers to speculate that regionally constrained strains were less infectious than widespread strains. Since the constrained strains persisted within their limited ranges, some researchers speculated that localized populations of the bacteria may have coevolved with their human hosts, making different human populations more susceptible to different types of TB. This could also mean, researchers hypothesized, that different strains of TB would have different susceptibility to different treatments and vaccines. For example, structural differences in the shape of the bacteria might prevent some drugs from binding effectively with bacteria from different strains.

Until recently, these hypotheses were nearly impossible to test, given the differences between cultural and environmental conditions that might affect infection rates in different communities and other parts of the world. Furthermore, the fact that the constrained stains strayed from home so rarely made it challenging to gather enough data to measure differences across strains.

Multidisciplinary science cracks the case

To overcome these obstacles, the research team collaborated with public health departments and research teams from the U.S., the Netherlands, and Germany to assemble a massive database integrating tuberculosis case reports, pathogen genetic profiles, and public health records of infection rates among close contacts. The analysis also incorporated demographic details about the social networks of infected people to assess how the different genetic lineages of tuberculosis spread in other populations. In total, the study included 5,256 TB cases and 28,889 close contacts.

“This study is a great example of why it’s so important for researchers to collaborate with many different kinds of partners,” said Groeschel. “We were able to merge public health data from three big cities and use the powerful computational biology tools that we have access to in academic medicine to answer a complicated question that has important implications for public health and evolutionary biology, vaccine development, and drug research.”

Authorship, funding, disclosures

Additional authors include Roger Vargas Jr of HMS; Francy Pérez-Llanos and Susanne Homolka of Research Center Borstel, Borstel, Germany; Roland Diel of University Medical Hospital Schleswig-Holstein; Vincent Escuyer and Kimberlee Musser of the Wadsworth Center, New York State Department of Health; Shama Ahuja, Lisa Trieu, Jeanne Sullivan Meissner, and Jillian Knorr of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Bureau of Tuberculosis Control; Dick van Soolingen and Don Klinkenberg of the National Tuberculosis Reference Laboratory, Center for Infectious Disease Control, National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), Bilthoven, The Netherlands; Peter Kouw of the Department of Infectious Diseases, Public Health Service, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Wojciech Samek of the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Technical University Berlin and the Department of Artificial Intelligence, Fraunhofer Heinrich Hertz Institute, Berlin, Germany; Barun Mathema of the Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University; and Stefan Niemann of the German Center for Infection Research, Partner Site Hamburg-Lübeck-Borstel-Riems, Borstel, Germany.

This work was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant R21AI154089), the German Research Foundation (GR5643/1-1), the BIH Charité Junior Digital Clinician Scientist Program funded by the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, the Berlin Institute of Health at Charité (BIH), the Leibniz Science Campus EvoLUNG (grant W47/2019), the German Research Foundation under Germany’s Excellence Strategy – EXC 2167 Precision Medicine in Inflammation, and the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) for the German Center of Infection Research (DZIF).

END

Which strains of tuberculosis are the most infectious?

Shared geographic origin between TB strain and human host could amplify risk for infection

2024-08-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New AI tool simplifies heart monitoring: Fewer leads, same accuracy

2024-08-01

LA JOLLA, CA—To diagnose heart conditions including heart attacks and heart rhythm disturbances, clinicians typically rely on 12-lead electrocardiograms (ECGs)—complex arrangements of electrodes and wires placed around the chest and limbs to detect the heart’s electrical activity. But these ECGs require specialized equipment and expertise, and not all clinics have the capability to perform them.

Now, a team of scientists and clinicians from Scripps Research has shown that heart conditions can be diagnosed roughly as accurately using just three electrodes and an artificial intelligence (AI) tool. In a ...

Tipping risks from overshooting 1.5°C can be minimized if warming is swiftly reversed

2024-08-01

Current climate policies imply a high risk for tipping of critical Earth system elements, even if temperatures return to below 1.5°C of global warming after a period of overshoot. A new study indicates that these risks can be minimized if warming is swiftly reversed.

Human-made climate change can lead to a destabilization of large-scale components of the Earth system such as ice sheets, ocean circulation patterns, or global biosphere components, the so-called tipping elements. In their new study published in Nature Communications, researchers from IIASA and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) analyzed the risks for four interconnected core climate tipping elements ...

Comprehensive meta-analysis pinpoints what vaccination strategies different countries should adopt

2024-08-01

Vaccines are safe and effective, and help reduce death and illness. But global vaccination rates are suboptimal and have trended downward, leaving humanity more vulnerable to vaccine-preventable diseases such as COVID-19, influenza, measles, polio, and HPV.

Identifying interventions that could increase vaccine coverage could help save lives. A new paper from a team led by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania offers the first comprehensive meta-analysis examining what types of vaccine intervention strategies have the ...

Predicting the future: Easy tool helps estimate fall risks

2024-08-01

Osaka, Japan — An aging society has posed a new global problem, the risk of falling. It is estimated that 1 in 3 adults over the age of 65 falls each year and the resulting injuries are becoming more prevalent.

To tackle this growing issue, Associate Professor Hiromitsu Toyoda and Specially Appointed Professor Tadashi Okano from Osaka Metropolitan University’s Graduate School of Medicine, together with Professor Chisato Hayashi from the University of Hyogo, have developed a formula and assessment tool for estimating fall risks that is simple for older adults to use. The tool was developed using data collected from older adults over a ten-year period from April 2010 to December ...

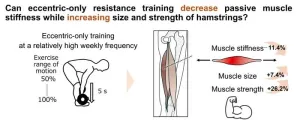

Eccentric-only resistance training can lower passive muscle stiffness

2024-08-01

Resistance, or weight training, is widely recommended in sports and rehabilitation as an effective exercise to increase muscular strength and size. This form of exercise involves applying resistance to muscle contraction to build strength. However, some practitioners believe resistance training can increase passive muscle stiffness over time. Passive muscle stiffness is a key indicator of how muscles behave mechanically when they are stretched without active contraction. Specifically, it refers to the amount of force required to change the muscle length by a given amount during passive stretching. Studies ...

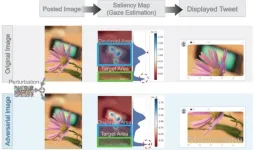

Enhancing automatic image cropping models with advanced adversarial techniques

2024-08-01

Image cropping is an essential task in many contexts, right from social media and e-commerce to advanced computer vision applications. Cropping helps maintain image quality by avoiding unnecessary resizing, which can degrade the image and consume computational resources. It is also useful when an image needs to conform to a predetermined aspect ratio, such as in thumbnails. Over the past decade, engineers around the world have developed various machine learning (ML) models to automatically crop images. These models aim to crop an input image in a way that preserves its most relevant parts.

However, ...

$2.4 million grant helping MCG scientists better understand what happens to our skeleton as we age

2024-08-01

AUGUSTA, Ga. (Aug. 1, 2024) – Figuring out how the tissues in our bones, adrenal glands, muscle and fat “talk” to each other could help scientists better understand what happens to our skeletons with age, when our bones tend to lose mass and become weaker, leaving us at risk for falls and fractures.

“Tissues don’t function in isolation – everything in the body “talks” to everything else to keep people healthy across the lifespan,” explains Meghan McGee-Lawrence, PhD, bone biologist at the Medical College of Georgia at ...

Using AI, USC researchers pioneer a potential new immunotherapy approach for treating glioblastoma

2024-08-01

In an innovative new study of glioblastoma, scientists used artificial intelligence (AI) to reprogram cancer cells, converting them into dendritic cells (DCs), which can identify cancer cells and direct other immune cells to kill them.

Glioblastoma is the most common brain cancer in adults and also the deadliest, with less than 10% of patients surviving five years after their diagnosis. While new approaches such as immunotherapy have revolutionized treatment for other cancers, they have done little for patients with glioblastoma. That is partly because these hard-to-reach brain tumors ...

High blood pressure associated with environmental contamination by tellurium

2024-08-01

The likelihood of developing high blood pressure (hypertension) increases with higher levels of tellurium, a contaminant transferred from mining and manufacturing activities to foods. Improved monitoring of tellurium levels in specific foods could help decrease high blood pressure in the general population. The results of a study examining the relationship between tellurium exposure and hypertension were published in the journal Environment International.

The study was led by Nagoya University in Japan. According to Takumi Kagawa, one of the researchers involved in the ...

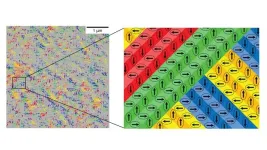

Pursuing the middle path to scientific discovery

2024-08-01

In electronic technologies, key material properties change in response to stimuli like voltage or current. Scientists aim to understand these changes in terms of the material’s structure at the nanoscale (a few atoms) and microscale (the thickness of a piece of paper). Often neglected is the realm between, the mesoscale — spanning 10 billionths to 1 millionth of a meter.

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory, in collaboration with Rice University and DOE’s Lawrence ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Middle-aged men are most vulnerable to faster aging due to ‘forever chemicals’

Starving cancer: Nutrient deprivation effects on synovial sarcoma

Speaking from the heart: Study identifies key concerns of parenting with an early-onset cardiovascular condition

From the Late Bronze Age to today - Old Irish Goat carries 3,000 years of Irish history

Emerging class of antibiotics to tackle global tuberculosis crisis

Researchers create distortion-resistant energy materials to improve lithium-ion batteries

Scientists create the most detailed molecular map to date of the developing Down syndrome brain

Nutrient uptake gets to the root of roots

Aspirin not a quick fix for preventing bowel cancer

HPV vaccination provides “sustained protection” against cervical cancer

Many post-authorization studies fail to comply with public disclosure rules

GLP-1 drugs combined with healthy lifestyle habits linked with reduced cardiovascular risk among diabetes patients

Solved: New analysis of Apollo Moon samples finally settles debate about lunar magnetic field

University of Birmingham to host national computing center

Play nicely: Children who are not friends connect better through play when given a goal

Surviving the extreme temperatures of the climate crisis calls for a revolution in home and building design

The wild can be ‘death trap’ for rescued animals

New research: Nighttime road traffic noise stresses the heart and blood vessels

Meningococcal B vaccination does not reduce gonorrhoea, trial results show

AAO-HNSF awarded grant to advance age-friendly care in otolaryngology through national initiative

Eight years running: Newsweek names Mayo Clinic ‘World’s Best Hospital’

Coffee waste turned into clean air solution: researchers develop sustainable catalyst to remove toxic hydrogen sulfide

Scientists uncover how engineered biochar and microbes work together to boost plant-based cleanup of cadmium-polluted soils

Engineered biochar could unlock more effective and scalable solutions for soil and water pollution

Differing immune responses in infants may explain increased severity of RSV over SARS-CoV-2

The invisible hand of climate change: How extreme heat dictates who is born

Surprising culprit leads to chronic rejection of transplanted lungs, hearts

Study explains how ketogenic diets prevent seizures

New approach to qualifying nuclear reactor components rolling out this year

U.S. medical care is improving, but cost and health differ depending on disease

[Press-News.org] Which strains of tuberculosis are the most infectious?Shared geographic origin between TB strain and human host could amplify risk for infection