(Press-News.org) Solving a decades-old problem, a multidisciplinary team of Caltech researchers has figured out a method to noninvasively and continually measure blood pressure anywhere on the body with next to no disruption to the patient. A device based on the new technique holds the promise to enable better vital-sign monitoring at home, in hospitals, and possibly even in remote locations where resources are limited.

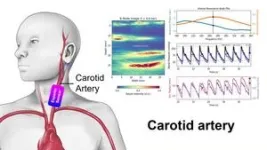

The new patented technique, called resonance sonomanometry, uses sound waves to gently stimulate resonance in an artery and then uses ultrasound imaging to measure the artery's resonance frequency, arriving at a true measurement of blood pressure. In a small clinical study, the device, which gives patients a gentle buzzing sensation on the skin, produced results akin to those obtained using the standard-of-care blood pressure cuff.

"We ended up with a device that is able to measure the absolute blood pressure—not only the systolic and diastolic numbers that we are used to getting from blood pressure cuffs—but the full waveform," says Yaser Abu-Mostafa (PhD '83), professor of electrical engineering and computer science and one of the authors of a new paper describing the technique and device in the journal PNAS Nexus. "With this device you can measure blood pressure continuously and in different sites on the body, giving you much more information about the blood pressure of a person."

"This team has been working for almost a decade, trying to build something that makes a difference, that is good enough to solve a real clinical problem," says Aditya Rajagopal (BS '08, PhD '14), visiting associate in electrical engineering at Caltech, research adjunct assistant professor of biomedical engineering at USC, and a co-author of the new paper. "Many groups, including tech giants like Apple and Google, have been working toward a solution like this, because it enables a spectrum of patient-monitoring possibilities from the hospital to the home. Our method broadens access to hospital-grade monitoring of blood pressure and cardiac health metrics."

Blood pressure 101

Blood pressure is simply the force of blood pushing on the walls of the body's blood vessels as it gets pumped around the body. High blood pressure, or hypertension, is related to risk of heart attack, stroke, chronic kidney disease, and other health problems. Low blood pressure, or hypotension, can also be a serious problem because it means the blood is not carrying enough oxygen to the organs. Taking regular measurements of blood pressure is considered one of the best ways to monitor overall health and to identify potential problems.

Most of us have experienced the cuff-style measurement of blood pressure. A nurse, doctor, or machine inflates a cuff that fits around the upper arm until blood can no longer flow, and then slowly releases the air from the cuff while listening for the sound that blood makes as it once again begins to flow. The pressure in the cuff at that point corresponds to the blood pressure in the patient's arteries. But this technique has limitations: It can only be performed periodically, as it involves occluding a blood vessel, and can only collect data from the arm.

Physicians would very much like to have continuous readings that provide full waveforms of a patient's blood pressure, and not only peripheral measurements from an arm but also central measurements from the chest and other parts of the body. To get the full information they need, intensive care physicians and surgeons sometimes resort to inserting a catheter directly into the artery of critical patients (a practice known as placing an arterial line, or "a-line"). This is invasive and can be risky, but, until now, it has been the only way to get a continuous readout of true blood pressure. In some cases, such as problems with heart valves, full blood-pressure waveforms can provide physicians with diagnostic information that they cannot get any other way.

"There's a lot of information in that waveform that is really valuable," says Alaina Brinley Rajagopal, a visiting associate in electrical engineering at Caltech, an emergency medicine physician, and a co-author of the paper. And other blood pressure devices developed over the last decade or two require a calibration step that emergency physicians simply do not have time for, she says. "I need to be able to put something on a patient and have it work immediately."

The new device fits the bill. The current prototype, built and tested by a spin-off company called Esperto Medical, is housed in a transducer case smaller than a deck of cards and is mounted on an armband, though the researchers say it could eventually fit within a package the size of a watch or adhesive patch. The team aims for the device to first be used in hospitals, where it would connect via wire to existing hospital monitors. It could mean that doctors would no longer have to weigh the risks of placing an a-line in order to get the continuous monitoring of real blood pressure for any patient.

Eventually, Brinley says their device could replace blood pressure cuffs as well. "Blood pressure cuffs only take one measurement as often as you run the cuff, so if you're asking patients to monitor their blood pressure at home, they have to know how to use the device, they have to put it on, and they have to be motivated to record the information, and I would say a majority of patients do not do that,” says Brinley Rajagopal. "Having a device like ours, where it is just place and forget, you can wear it all day, and it can take however many measurements your provider wants, that would allow for better, precision dosing of medication."

Developing a game changer

Rajagopal recalls the long road it has been getting to this point with the blood pressure device. About a decade ago, Brinley Rajagopal returned from a global health trip particularly frustrated by the standard of care she could provide patients in remote locations. Talking with Rajagopal, the two wished they could invent something like a medical tricorder, a handheld device seen in Star Trek that helped the fictional doctors of the future scan patients, gather medical information, and diagnose. "That got us thinking about technologies we could adapt to get us closer to a goal like that,” says Brinley Rajagopal. Those initial sci-fi–inspired discussions eventually led them down the path to try to develop a better blood pressure monitor.

But their first efforts did not pan out. After years of work on a possible solution using blood velocity to derive blood pressure, the team decided that they had reached a dead end. As with many other current blood pressure monitoring devices, that approach could only provide the relative blood pressure—the difference between the high and low measurements without the absolute number. It also required calibration.

Back to the drawing board

Rajagopal decided it was time to reevaluate and determine if they had any chance of solving this problem. "It was this moment of desperation that actually led to the key insight," says Rajagopal.

Thinking back to his first-year physics course at Caltech, he began scribbling on a nearby wall. He remembered that his Physics1 textbook presented a canonical problem: You have a string under tension. How can you determine how taut the line is? If you tweeze the string, you can relate the velocity at which vibration waves travel back and forth on the string to the resonance frequency in the string, which could give you your answer. "I thought if I could stretch an artery in one direction and magically tweeze it and let it go, the ringing would give us the resonance frequency, which would get us to blood pressure," says Rajagopal. After six years of failures and returning to first principles, they finally had their guiding insight.

And indeed, that is the underlying idea behind the new device: Like a guitar changing pitch as it is plucked while being tightened, the frequency at which an artery resonates when struck by sound waves changes depending on the pressure of the blood it contains.

This resonance frequency can be measured with ultrasound, providing a measure of blood pressure. This measurement requires three parameters—a measurement of the artery's radius, the thickness of the artery's walls, and the tension or energy in the skin of the artery.

With the physics worked out, there were still a lot of other details to be resolved—identifying the sound waves that would make arteries resonate, understanding how to measure that resonance, and then determining how to efficiently map that back to blood pressure, and, significantly, how to build a working system.

"Building that system required some extraordinarily bespoke technologies," says Rajagopal. Caltech alumnus Raymond Jimenez (BS '13) was instrumental in building out that first system. "The art form, which involved a lot of other Caltech alumni, was to put the physics answer into a very simple, practical instrument."

The resulting Esperto device is small, noninvasive, relatively inexpensive, and it has an automated method for locating the patient's blood vessel without needing to be physically repositioned. It also does not suffer from the problems that some blood pressure monitoring devices have, such as not being accurate for patients with low blood pressure or getting varying results depending on a patient's skin tone.

It might not be a medical tricorder, but the team says the device solves the longstanding blood pressure monitoring problem. And Rajagopal says it is the product of a million small leaps. "Everything we've done is a product of the exact mistakes we've made over time,” he says, "and all the work that others have done too."

"This work is emblematic of what makes Caltech so remarkable: solving a very hard problem by going back to first principles and understanding a physical phenomenon at the fundamental level," says Fred Farina, Caltech's Chief Innovation and Corporate Partnerships Officer. "This approach, combined with the tenacity and entrepreneurial drive of the team, is our homemade recipe for societal impact and improving people’s lives."

The paper describing the new technique is titled "Resonance sonomanometry for noninvasive, continuous monitoring of blood pressure." Additional authors on the paper include Raymond Jimenez (BS '13), Steven Dell, Austin C. Rutledge, Matt K. Fu (BS '13), and William P. Dempsey (PhD '12) of Esperto Medical, and Dominic Yurk (BS '17, PhD '23), a current member of Abu-Mostafa's group at Caltech. The work at Caltech was supported by Caltech trustee Charles Trimble (BS '63, MS '64), the Carver Mead Innovation Fund, and the Grubstake Fund.

END

CalTech team develops first noninvasive method to continually measure true blood pressure

Device uses sound waves to gather blood pressure data from blood vessels, monitoring the response with ultrasound.

2024-08-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Using photos or videos, these AI systems can conjure simulations that train robots to function in physical spaces

2024-08-07

Researchers working on large artificial intelligence models like ChatGPT have vast swaths of internet text, photos and videos to train systems. But roboticists training physical machines face barriers: Robot data is expensive, and because there aren’t fleets of robots roaming the world at large, there simply isn’t enough data easily available to make them perform well in dynamic environments, such as people’s homes.

Some researchers have turned to simulations to train robots. Yet even that process, which often involves a graphic designer ...

When is too much knowledge a bad thing?

2024-08-07

CORNELL UNIVERSITY MEDIA RELATIONS OFFICE

FOR RELEASE: August 7, 2024

Kaitlyn Serrao

607-882-1140

kms465@cornell.edu

When is too much knowledge a bad thing?

ITHACA, N.Y. – A new study finds an increase in knowledge could be a bad thing when people use it to act in their own self-interest rather than in the best interests of the larger group.

Cornell University economics professor Kaushik Basu and Jörgen Weibull, professor emeritus at the Stockholm School of Economics, are co-authors ...

Do smells prime our gut to fight off infection?

2024-08-07

Many organisms react to the smell of deadly pathogens by reflexively avoiding them. But a recent study from the University of California, Berkeley, shows that the nematode C. elegans also reacts to the odor of pathogenic bacteria by preparing its intestinal cells to withstand a potential onslaught.

As with humans, nematodes’ guts are a common target of disease-causing bacteria. The nematode reacts by destroying iron-containing organelles called mitochondria, which produce a cell's energy, to protect this critical element from iron-stealing bacteria. Iron is a key catalyst in many enzymatic reactions in cells — in particular, ...

mTORC1 in classical monocytes: Links to human size variation & neuropsychiatric disease

2024-08-07

"This report suggests that a simple assay may allow cost-effective prediction of medication response."

BUFFALO, NY- August 7, 2024 – A new research paper was published in Aging (listed by MEDLINE/PubMed as "Aging (Albany NY)" and "Aging-US" by Web of Science), Volume 16, Issue 14 on July 26, 2024, entitled, “mTORC1 activation in presumed classical monocytes: observed correlation with human size variation and neuropsychiatric disease.”

In this new study, researchers Karl Berner, Naci Oz, Alaattin Kaya, Animesh Acharjee, and Jon Berner ...

In Parkinson’s, dementia may occur less often, or later, than thought

2024-08-07

MINNEAPOLIS – There’s some good news for people with Parkinson’s disease: The risk of developing dementia may be lower than previously thought, or dementia may occur later in the course of the disease than previously reported, according to a study published in the August 7, 2024, online issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology.

“The development of dementia is feared by people with Parkinson’s, and the combination of both a movement disorder and a cognitive disorder can be devastating to them and their loved ones,” said study author Daniel Weintraub, MD, ...

Impact of drought on drinking water contamination: disparities affecting Latino/a communities

2024-08-07

Long-term exposure to contaminants such as arsenic and nitrate in water is linked to an increased risk of various diseases, including cancers, cardiovascular diseases, developmental disorders and birth defects in infants. In the United States, there is a striking disparity in exposure to contaminants in tap water provided by community water systems (CWSs), with historically marginalized communities at greater risks compared to other populations. Often, CWSs that distribute water with higher contamination levels exist in areas that lack adequate public infrastructure or sociopolitical and financial resources.

In ...

Pesticide exposure linked to stillbirth risk in new study

2024-08-07

Living less than about one-third of a mile from pesticide use prior to conception and during early pregnancy could increase the risk of stillbirths, according to new research led by researchers at the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health and Southwest Environmental Health Sciences Center.

Researchers found that during a 90-day pre-conception window and the first trimester of pregnancy, select pesticides, including organophosphates as a class, were associated with stillbirth.

The paper, “Pre-Conception ...

Individuals vary in how air pollution impacts their mood

2024-08-07

Affective sensitivity to air pollution (ASAP) describes the extent to which affect, or mood, fluctuates in accordance with daily changes in air pollution, which can vary between individuals, according to a study published August 7, 2024 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Michelle Ng from Stanford University, USA, and colleagues.

Individuals’ sensitivity to climate hazards is a central component of their vulnerability to climate change. Building on known associations between air pollution exposure and ...

Repetition boosts belief in climate-skeptical claims, even among climate science endorsers

2024-08-07

Climate science supporters rated climate-skeptical statements as “truer” after just a single repetition, according to a study published August 7, 2024 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE led by Mary Jiang from The Australian National University, Australia, and coauthored by Norbert Schwarz from the University of Southern California, USA, and colleagues. The results held true even for the strongest climate science supporters surveyed.

Amidst the influx of content that a person consumes each day, the principle of motivated ...

Study quantifies air pollution for NYC subway commuters

2024-08-07

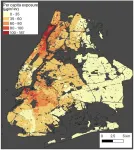

New York City subway commuters who are economically disadvantaged or belong to racial minority groups have the highest exposure to fine particulate matter during their commutes, according to a new study published August 7, 2024 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Shams Azad of New York University, USA.

Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) is a type of air pollution that, due to its small size, when inhaled by a person can enter the bloodstream. PM2.5 is known to cause short- and long-term health complications. For the last few decades, cities have promoted public transportation to reduce traffic congestion and improve ambient outdoor air quality. Subway systems reduce pollution by decreasing ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Increasing the number of coronary interventions in patients with acute myocardial infarction does not appear to reduce death rates

Tackling uplift resistance in tall infrastructures sustainably

Novel wireless origami-inspired smart cushioning device for safer logistics

Hidden genetic mismatch, which triples the risk of a life-threatening immune attack after cord blood transplantation

Physical function is a crucial predictor of survival after heart failure

Striking genomic architecture discovered in embryonic reproductive cells before they start developing into sperm and eggs

Screening improves early detection of colorectal cancer

New data on spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) – a common cause of heart attacks in younger women

How root growth is stimulated by nitrate: Researchers decipher signalling chain

Scientists reveal our best- and worst-case scenarios for a warming Antarctica

Cleaner fish show intelligence typical of mammals

AABNet and partners launch landmark guide on the conservation of African livestock genetic resources and sustainable breeding strategies

Produce hydrogen and oxygen simultaneously from a single atom! Achieve carbon neutrality with an 'All-in-one' single-atom water electrolysis catalyst

Sleep loss linked to higher atrial fibrillation risk in working-age adults

Visible light-driven deracemization of α-aryl ketones synergistically catalyzed by thiophenols and chiral phosphoric acid

Most AI bots lack basic safety disclosures, study finds

How competitive gaming on discord fosters social connections

CU Anschutz School of Medicine receives best ranking in NIH funding in 20 years

Mayo Clinic opens patient information office in Cayman Islands

Phonon lasers unlock ultrabroadband acoustic frequency combs

Babies with an increased likelihood of autism may struggle to settle into deep, restorative sleep, according to a new study from the University of East Anglia.

National Reactor Innovation Center opens Molten Salt Thermophysical Examination Capability at INL

International Progressive MS Alliance awards €6.9 million to three studies researching therapies to address common symptoms of progressive MS

Can your soil’s color predict its health?

Biochar nanomaterials could transform medicine, energy, and climate solutions

Turning waste into power: scientists convert discarded phone batteries and industrial lignin into high-performance sodium battery materials

PhD student maps mysterious upper atmosphere of Uranus for the first time

Idaho National Laboratory to accelerate nuclear energy deployment with NVIDIA AI through the Genesis Mission

Blood test could help guide treatment decisions in germ cell tumors

New ‘scimitar-crested’ Spinosaurus species discovered in the central Sahara

[Press-News.org] CalTech team develops first noninvasive method to continually measure true blood pressureDevice uses sound waves to gather blood pressure data from blood vessels, monitoring the response with ultrasound.