Millions of years for plants to recover from global warming

2024-08-08

(Press-News.org)

In brief:

Disruption of the functioning of vegetation due to warming can lead to the failure of climate regulating mechanisms for millions of years.

Vegetation changes can alter the planet’s climate equilibrium.

Geological and climatic history provide insight into the effects of global warming today.

Scientists often seek answers to humanity’s most pressing challenges in nature. When it comes to global warming, geological history offers a unique, long-term perspective. Earth’s geological history is spiked by periods of catastrophic volcanic eruptions that released vast amounts of carbon into the atmosphere and oceans. The increased carbon triggered rapid climate warming that resulted in mass extinctions on land and in marine ecosystems. These periods of volcanism may also have disrupted carbon-climate regulation systems for millions of years.

Ecological imbalance

Earth and environmental scientists at ETH Zurich led an international team of researchers from the University of Arizona, University of Leeds, CNRS Toulouse, and the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest Snow and Landscape Research (WSL) in a study on how vegetation responds and evolves in response to major climatic shifts and how such shifts affect Earth’s natural carbon-climate regulation system.

Drawing on geochemical analyses of isotopes in sediments, the research team compared the data with a specially designed model, which included a representation of vegetation and its role in regulating the geological climate system. They used the model to test how the Earth system responds to the intense release of carbon from volcanic activity in different scenarios. They studied three significant climatic shifts in geological history, including the Siberian Traps event that caused the Permian-Triassic mass extinction about 252 million years ago. ETH Zurich professor, Taras Gerya points out, “The Siberian Traps event released some 40,000 gigatons (Gt) of carbon over 200,000 years. The resulting increase in global average temperatures between 5 - 10°C caused Earth’s most severe extinction event in the geologic record”.

Move, adapt, or perish

“The recovery of vegetation from the Siberian Traps event took several millions of years and during this time Earth’s carbon-climate regulation system would have been weak and inefficient resulting in long-term climate warming,” explains lead author, Julian Rogger, ETH Zurich.

Researchers found that the severity of such events is determined by how fast emitted carbon can be returned to Earth’s interior – sequestered through silicate mineral weathering or organic carbon production, removing carbon from Earth’s atmosphere. They also found that the time it takes for the climate to reach a new state of equilibrium depended on how fast vegetation adapted to increasing temperatures. Some species adapted by evolving and others by migrating geographically to cooler regions. However, some geological events were so catastrophic that plant species simply did not have enough time to migrate or adapt to the sustained increase in temperature. The consequences of which left its geochemical mark on climate evolution for thousands, possibly millions, of years.

Today’s human-induced climate crisis

What does this mean for human induced climate change? The study found that a disruption of vegetation increased the duration and severity of climate warming in the geologic past. In some cases, it may have taken millions of years to reach a new stable climatic equilibrium due to a reduced capacity of vegetation to regulate Earth’s carbon cycle.

“Today, we find ourselves in a major global bioclimatic crisis,” comments Loïc Pellissier, Professor of Ecosystems and Landscape Evolution at ETH Zurich and WSL. “Our study demonstrates the role of a functioning of vegetation to recover from abrupt climatic changes. We are currently releasing greenhouse gases at a faster rate than any previous volcanic event. We are also the primary cause of global deforestation, which strongly reduces the ability of natural ecosystems to regulate the climate. This study, in my perspective, serves as ‘wake-up call’ for the global community.”

END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2024-08-08

[Vienna, August 7 2024] — The ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine has led to severe humanitarian crises, including widespread food shortages. According to the United Nations World Food Programme, an estimated 11 million Ukrainians—about one-third of the population—were at risk of hunger in 2023. This crisis, exacerbated by supply chain disruptions and extreme weather events, could increase diabetes prevalence not only in Ukraine but globally, argue Peter Klimek and Stefan Thurner from the Complexity Science Hub in a commentary published in the journal Science.

Malnutrition during early pregnancy is known to elevate diabetes ...

2024-08-08

August 8, 2024—(BRONX NY)—A discovery by a three-member Albert Einstein College of Medicine research team may boost the effectiveness of stem-cell transplants, commonly used for patients with cancer, blood disorders, or autoimmune diseases caused by defective stem cells, which produce all the body’s different blood cells. The findings, made in mice, were published today in the journal Science.

“Our research has the potential to improve the success of stem-cell transplants and expand their use,” explained Ulrich Steidl, ...

2024-08-08

While seeking to unravel how marine algae create their chemically complex toxins, scientists at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography have discovered the largest protein yet identified in biology. Uncovering the biological machinery the algae evolved to make its intricate toxin also revealed previously unknown strategies for assembling chemicals, which could unlock the development of new medicines and materials.

Researchers found the protein, which they named PKZILLA-1, while studying how a type of algae called Prymnesium parvum makes its toxin, which is responsible for massive fish kills.

“This is the Mount Everest of proteins,” ...

2024-08-08

Voids or pores have usually been viewed as fatal flaws that severely degrade a material's mechanical performance and should be eliminated in manufacturing.

However, a research team led by Prof. JIN Haijun from the Institute of Metal Research (IMR) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences has proposed that the presence of voids is not always hazardous. Instead, voids can be beneficial if they are added "properly" to the material.

The team demonstrated that a metal with a large number of nanoscale voids shows improved ...

2024-08-08

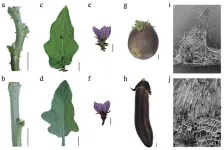

Scientists have discovered the gene responsible for prickles in eggplants, a trait that complicates farming. Using advanced genetic techniques, they identified the Prickly Eggplant (PE) gene on chromosome 6 and pinpointed SmLOG1 as the key factor. CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing confirmed that disabling SmLOG1 eliminates prickles, paving the way for prickle-free eggplant varieties. This breakthrough not only sheds light on prickle development but also promises to streamline eggplant cultivation and harvesting, benefiting the agricultural industry.

Eggplants, a staple crop globally, present significant challenges in cultivation and harvesting due to their prickles. These prickles, which serve as ...

2024-08-08

People eat either because they are hungry or for pleasure, even in the absence of hunger. While hunger-driven eating is fundamental for survival, pleasure-driven feeding may accelerate the onset of obesity and associated metabolic disorders. A study published in Nature Metabolism reveals neural circuits in the mouse brain that promote hunger-driven feeding and suppress pleasure-driven eating. The findings open new possibilities for developing strategies to combat obesity.

“Ideal feeding habits would balance eating for necessity and for pleasure, minimizing the latter,” said co-corresponding author Dr. Yong Xu, ...

2024-08-08

“These findings indicate that renalase-1 is a potential antigen for TCR recognition in melanoma and could be considered as a target for immunotherapy.”

BUFFALO, NY- August 8, 2024 – A new research paper was published in Oncotarget's Volume 15 on August 5, 2024, entitled, “Chemical complementarity of tumor resident, T-cell receptor CDR3s and renalase-1 correlates with increased melanoma survival.”

As mentioned in the Abstract of this study, overexpression of the secretory protein renalase-1 negatively impacts the survival of melanoma and pancreatic cancer patients, while inhibition of renalase-1 signaling drives tumor ...

2024-08-08

Key Takeaways

-Fusion has the potential to provide abundant clean energy

-One to two-year awards range from $100,000 to $500,000

In a continuing effort to forge and fund public-private partnerships to accelerate fusion research, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) today awarded $4.6 million in 17 awards to U.S. businesses via the Innovation Network for Fusion Energy (INFUSE) program.

The goal of INFUSE is to accelerate fusion energy development in the private sector by reducing impediments to collaboration between business ...

2024-08-08

Following the Mediterranean diet versus the traditional Western diet might make you feel like you’re under less stress, according to new research conducted by a team from Binghamton University, State University of New York.

The findings suggest that people can lower their perception of how much stress they can tolerate by following a Mediterranean diet, said Lina Begdache, associate professor of health and wellness studies.

“Stress is recognized to be a precursor to mental distress, and research, including our own, has demonstrated that the Mediterranean diet lowers ...

2024-08-08

A recent study investigates the intricate mechanisms of sugar import in developing seeds of Camellia oleifera. By identifying key sugar transporters and analyzing their roles, the research provides significant insights into the molecular regulation of seed development. The findings highlight how these transporters, working alongside sucrose-metabolizing enzymes, facilitate efficient sugar import and partitioning. This study not only advances our understanding of seed development in Camellia oleifera but also suggests potential strategies to enhance seed yield and quality in this important ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Millions of years for plants to recover from global warming