(Press-News.org) Experiments conducted by UC Merced researchers find that people who perform good deeds are far more likely to be thought of as religious believers than atheists. Moreover, the psychological bias linking kindness and helpfulness with faith appears to be global in scale.

Research on the mental link between moral behavior and religious belief goes back more than a decade. Prior research, however, emphasized the dark side of this equation, with participants asked whether they assumed it was more probable that a serial killer believed in God or was an atheist (people in nations all over the planet thought the latter was more likely).

The UC Merced studies, conceptualized by cognitive science graduate student Alex Dayer and published this week in the journal Scientific Reports, flipped the switch to the bright side: What if someone was a “serial helper,” prone to extraordinary benevolence?

The research found that the stereotype of an extraordinarily good person being religious was dramatically stronger that of an extraordinarily cruel person being an atheist, said co-author Colin Holbrook, a professor in the university’s Department of Cognitive and Information Sciences .

“Though we also found that people intuitively link atheism with immoral behavior, people appear to associate believing in God with being generous, helpful and caring to a much greater extent,” Holbrook said.

The research consisted of experiments conducted in two nations with disparate levels of religious belief:

The United States, where 47% of the population describes itself as religious, according to a recent Gallup poll.

New Zealand, where 49% of respondents in the 2018 census indicated no religious belief.

Participants read a description of a man who took a path of increasing benevolence, from helping stray animals as a child to, as an adult, giving food and clothes to homeless people. Sometimes, during bitingly cold weather, he offered a spare room to homeless families.

Half of the participants were asked which is more probable: The man is a teacher or the man is a teacher and believes in God. The other half were asked the same question, but the options were “the man is a teacher” or “the man is a teacher and does not believe in God.”

The most logical response would be to guess the man is a teacher, a group that would include both teachers who believe and teachers who are atheists. But people have been found to pick the less likely option to this type of question if it matches a strong social stereotype in their minds.

The results were striking. U.S. respondents were nearly 20 times more likely to guess that the helpful man believed in God than that the man was an atheist. In New Zealand, respondents were 12 times more likely to guess that the helpful man was religious.

The bias intuitively connecting religious belief to socially uplifting behavior was significantly stronger than that found with the study’s inverse, “dark side” conditions, which looked for stereotypes of atheists as antisocial. The bias was there, but far less powerful.

“So instead of a stereotype of atheists as immoral driving the effect, the stereotype of the moral person of faith may be the more important force,” Holbrook said. “We replicated the findings of the earlier studies linking evil with atheism, but we found that the effects linking prosociality with faith were remarkably larger.”

The study’s results fit with a theory about the historical development of major world religions that emphasizes cooperation. Belief that a powerful being or spiritual force rewards positive moral behavior – and punishes immoral behavior – is shared by all major religions. This kind of belief might help members of religious groups trust one another, cooperate and grow.

“Strangers with little in common beyond their shared spiritual beliefs in moralizing gods might be more inclined to trust and less inclined to exploit one another,” Holbrook said.

Of course, the UC Merced experiments and similar research measure only what stereotypes people project onto others – how they think someone would act based on what they believe.

“Our evidence indicates that people stereotype believers as more likely to care about and help others. But this theoretical model suggests that the stereotype might actually have had merit in the past as major religions grew or may possibly be true even now — people who believe in God might actually be more likely to help others,” Holbrook said. “The evidence that believers are more prosocial is currently mixed, and it’s a question that calls for more research.”

END

Psychological bias links good deeds to a belief in God, research says

2024-08-09

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Greenland megatsunami led to week-long oscillating fjord wave

2024-08-09

In September 2023, a megatsunami in remote eastern Greenland sent seismic waves around the world, piquing the interest of the global research community.

The event created a week-long oscillating wave in Dickson Fjord, according to a new report in The Seismic Record.

Angela Carrillo-Ponce of GFZ German Research Centre for Geoscience and her colleagues identified two distinct signals in the seismic data from the event: one high-energy signal caused by the massive rockslide that generated the tsunami, and one very long-period (VLP) signal that lasted over a week.

Their analysis of the VLP signal—which was detected as far as 5000 kilometers away—suggests ...

Machine learning approach helps researchers design better gene-delivery vehicles for gene therapy

2024-08-08

Gene therapy could potentially cure genetic diseases but it remains a challenge to package and deliver new genes to specific cells safely and effectively. Existing methods of engineering one of the most commonly used gene-delivery vehicles, adeno-associated viruses (AAV), are often slow and inefficient.

Now, researchers at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard have developed a machine-learning approach that promises to speed up AAV engineering for gene therapy. The tool helps researchers engineer the protein shells of AAVs, called capsids, to have multiple desirable ...

Bacteria encode hidden genes outside their genome—do we?

2024-08-08

NEW YORK, NY (Aug. 8, 2024) -- Since the genetic code was first deciphered in the 1960s, our genes seemed like an open book. By reading and decoding our chromosomes as linear strings of letters, like sentences in a novel, we can identify the genes in our genome and learn why changes in a gene’s code affect health.

This linear rule of life was thought to govern all forms of life—from humans down to bacteria.

But a new study by Columbia researchers shows that bacteria break that rule and can create free-floating and ephemeral genes, raising the possibility that similar genes exist outside ...

Assistant professor's $1.1M NASA grant to develop computational tool aiding hypersonic vehicle design

2024-08-08

STARKVILLE, Miss.—NASA is awarding a Mississippi State University assistant professor a $1.13 million grant to develop a new simulation tool to aid the design of hypersonic vehicles used in space exploration.

Vilas Shinde of MSU’s Department of Aerospace Engineering won the grant to develop a new flow stability and transition analysis tool, which will aid researchers and aircraft designers in understanding and predicting changes associated with the boundary layer—air flow in the vicinity of an aircraft’s ...

Houston Methodist study shows new, more precise way to deliver medicine to the brain

2024-08-08

Houston Methodist researchers have discovered a more accurate and timely way to deliver life-saving drug therapies to the brain, laying the groundwork for more effective treatment of brain tumors and other neurological diseases.

In a study published this month in Communications Biology, an open access journal from Nature Portfolio, investigators used an electric field to infuse medicine from a reservoir outside the brain to specific targets inside the brain. This adds a new dimension to the 30-year-old process of injecting therapeutics into the brain through ...

A ‘thank you’ goes a long way in family relationships

2024-08-08

URBANA, Ill. – You’ve probably heard that cultivating gratitude can boost your happiness. But in marriage and families, it’s not just about being more grateful for your loved ones — it’s also important to feel appreciated by them. Researchers at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign have previously explored the positive impact of perceived gratitude from romantic partners for couples’ relationship quality. In a new study, they show the benefits of perceived gratitude ...

How a legal loophole allows unsafe ingredients in US foods

2024-08-08

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is tasked with overseeing the safety of the U.S. food supply, setting requirements for nutrition labeling, working with companies on food recalls, and responding to outbreaks of foodborne illness. But when it comes to additives already in our food and the safety of certain ingredients, FDA has taken a hand-off approach, according to a new article in the American Journal of Public Health.

The current FDA process allows the food industry to regulate itself when it comes to thousands of added ...

USC researchers develop AI model that predicts the accuracy of protein–DNA binding

2024-08-08

A new artificial intelligence model developed by USC researchers and published in Nature Methods can predict how different proteins may bind to DNA with accuracy across different types of protein, a technological advance that promises to reduce the time required to develop new drugs and other medical treatments.

The tool, called Deep Predictor of Binding Specificity (DeepPBS), is a geometric deep learning model designed to predict protein–DNA binding specificity from protein–DNA complex structures. DeepPBS ...

Increasing solid-state electrolyte conductivity and stability using helical structure

2024-08-08

Solid-state electrolytes have been explored for decades for use in energy storage systems and in the pursuit of solid-state batteries. These materials are safer alternatives to the traditional liquid electrolyte—a solution that allows ions to move within the cell—used in batteries today. However, new concepts are needed to push the performance of current solid polymer electrolytes to be viable for next generation materials.

Materials science and engineering researchers at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign have explored the role of helical secondary structure on the conductivity of solid-state peptide polymer ...

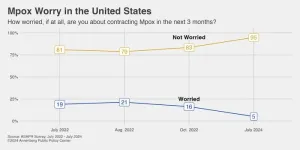

The threat of mpox has returned, but public knowledge about it has declined

2024-08-08

PHILADELPHIA – It has been two years since the World Health Organization declared a global health emergency over an outbreak of mpox, a disease endemic to Africa that had spread to scores of countries. Now, in the summer of 2024, a deadlier version of the infectious disease has spread from the Democratic Republic of Congo to other African nations, the strain that originally hit the United States has shown signs of a resurgence, and this week the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a new alert on mpox to health care providers.

But while the American public quickly learned about the disease during the summer of 2022, as ...