(Press-News.org) Researchers have demonstrated a technique for printing thin metal oxide films at room temperature, and have used the technique to create transparent, flexible circuits that are both robust and able to function at high temperatures.

“Creating metal oxides that are useful for electronics has traditionally required making use of specialized equipment that is slow, expensive, and operates at high temperatures,” says Michael Dickey, co-corresponding author of a paper on the work and the Camille and Henry Dreyfus Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at North Carolina State University. “We wanted to develop a technique to create and deposit metal oxide thin films at room temperature, essentially printing metal oxide circuits.”

Metal oxides are an important material found in nearly every electronic device. Most metal oxides are electrically insulating (like glass). But some metal oxides are both conductive and transparent, and those oxides are critically important for the touch screen on your smart phone or the monitor on your computer.

“In principle, metal oxide films should be easy to make,” Dickey says. “After all, they form naturally on the surface of nearly every metal object in our homes – soda cans, stainless steel pots, and forks. Although these oxides are everywhere, they are of limited use since they can’t be removed from the metals they form on.”

For this work, the researchers developed a novel way to separate metal oxide from a meniscus of liquid metal. If you fill a tube with liquid, a meniscus is the curved surface of the liquid that extends beyond the end of the tube. It’s curved because of the surface tension that prevents the liquid from spilling out completely. In the case of liquid metals, the surface of the meniscus is covered with a thin metal oxide skin that forms where the liquid metal meets the air.

“We fill the space between two glass slides with liquid metal so that a small meniscus extends beyond the ends of the slides,” Dickey says. “Think of the slides as the printer, and the liquid metal is the ink. The meniscus of liquid metal can then be brought into contact with a surface. The meniscus is covered with oxide on all sides, analogous to the thin rubber that encases a water balloon. When we move the meniscus across the surface, the metal oxide on the front and back of the meniscus sticks to the surface and peels off, like the trail left behind by a snail. As this happens, the exposed liquid on the meniscus constantly forms fresh oxide to enable continuous printing.”

The result is that the printer lays down a two-layer thin film of metal oxide that is approximately 4 nm thick.

“It’s important to note that even though we use a liquid, the metal oxide film deposited on the substrate is solid and incredibly thin,” Dickey says. “The film adheres to the substrate – it’s not something you could smudge or smear. That’s important for printing circuits.”

The researchers demonstrated this technique with several liquid metals and metal alloys, with each metal altering the composition of the metal oxide film. The researchers were also able to lay down a stack of layered thin films by making multiple passes with the printer. Video of the technique can be found at https://youtu.be/yT7Jzw5Ak2U?si=mqOBoWn4dKnApWgw.

“One of the things we found surprising was that the printed films are transparent but have metallic properties,” Dickey says. “They are highly conductive.”

“Because the films have a metallic character, gold bonds to the printed oxide, which is unusual – gold normally doesn’t stick to oxides,” says Unyong Jeong, co-corresponding author of a paper on the work and a professor of materials science and engineering at Pohang University of Science and Technology (POSTECH). “When you introduce a small amount of gold to these thin films, the gold is essentially incorporated into the film. This helps prevent the conductive properties of the oxide from degrading over time.”

“We think these films are so conductive because the center of the two-layer thin film contains very little oxygen, it’s more metallic and less of an oxide,” Jeong says. “Without the presence of gold, more oxygen makes its way to the center of the layered thin film over time, which causes the film to become electrically insulating. Adding gold to the thin film helps prevent the central part of the film from oxidizing. The fact that this works so well is surprising because we’re using so little gold – the oxide thin film is still highly transparent.”

In addition, the researchers found that the thin films retained their conductive properties at high temperatures. If the thin film is 4 nanometers thick, it retains its conductive properties up to almost 600 degrees Celsius. If the thin film is 12 nanometers thick, it retains its conductive properties up to at least 800 degrees Celsius.

The researchers also demonstrated the utility of their technique by printing metal oxides onto a polymer, creating highly flexible circuits that were robust enough to retain their integrity even after being folded 40,000 times.

“The films can also be transferred to other surfaces, such as leaves, to create electronics in unconventional places,” Dickey says. “We’re preserving the intellectual property on this technique and are open to working with industry partners to explore potential applications.”

The paper, “Ambient Printing of Native Oxides for Ultrathin Transparent Flexible Circuit Boards,” will be published August 15 in the journal Science. Co-first authors of the paper are Minsik Kong, a former visiting scholar at NC State and Ph.D. student at POSTECH; and Man Hou Vong, a Ph.D. student at NC State. The paper was co-authored by Omar Awartani, a former postdoctoral researcher at NC State; Mingyu Kwak, Ighyun Lim and Younghyun Lee of POSTECH; Seong-hun Lee, Jimin Kwon and Tae Joo Shin of Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology; and Insang You of the University of Waterloo.

This work was done with support from the National Research Foundation of Korea, funded by the Ministry of Science, under grants 2022M3C1A3081359 and RS-2024-00338686.

END

New technique prints metal oxide thin film circuits at room temperature

2024-08-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Sleep resets neurons for new memories the next day

2024-08-15

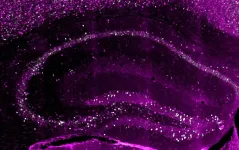

ITHACA, N.Y. – While everyone knows that a good night’s sleep restores energy, a new Cornell University study finds it resets another vital function: memory.

Learning or experiencing new things activates neurons in the hippocampus, a region of the brain vital for memory. Later, while we sleep, those same neurons repeat the same pattern of activity, which is how the brain consolidates those memories that are then stored in a large area called the cortex. But how is it that we can keep learning new things for a lifetime without using up all of our neurons?

A new study, “A Hippocampal Circuit Mechanism ...

Navigating the future: brain cells that plan where to go

2024-08-15

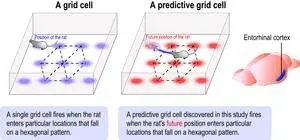

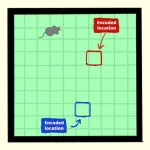

Researchers from the RIKEN Center for Brain Science (CBS) in Japan have discovered a region of the brain that encodes where an animal is planning to be in the near future. Linked to internal maps of spatial locations and past movements, activity in the newly discovered grid cells accurately predicts future locations as an animal travels around its environment. Published in Science on August 15, the study helps explain how planned spatial navigation is possible.

It might seem effortless, but navigating the world requires quite a bit of under-the-hood brain activity. For ...

The brain creates three copies for a single memory

2024-08-15

The ability to turn experiences into memories allows us to learn from the past and use what we learned as a model to respond appropriately to new situations. For this reason, as the world around us changes, this memory model cannot simply be a fixed archive of the good old days. Rather, it must be dynamic, changing over time and adapting to new circumstances to better help us predict the future and select the best course of action. How the brain could regulate a memory’s dynamics was a mystery – until multiple memory copies ...

Breakthrough addresses sex-related weight gain and disease

2024-08-15

ITHACA, N.Y. -- A decline in estrogen during menopause causes changes in body fat distribution and associated cardiovascular and metabolic disease, but a new study identifies potential therapies that might one day reverse these unhealthy shifts.

The study, “Cxcr4 Regulates a Pool of Adipocyte Progenitors and Contributes to Adiposity in a Sex-Dependent Manner,” was published Aug. 5 in Nature Communications.

The researchers discovered that a receptor called Cxcr4, when blocked in mice, reduced the tendency of fat stem cells to develop into white fat, also called white adipose tissue. This treatment could potentially be combined with low doses of estrogen therapy to cut ...

As human activities expand in Antarctica, scientists identify crucial conservation sites

2024-08-15

A team of scientists led by the University of Colorado Boulder has identified 30 new areas critical for conserving biodiversity in the Southern Ocean surrounding Antarctica. In a study published Aug. 15 in the journal Conservation Biology, the researchers warn that without greater protection to limit human activities in these areas, native wildlife could face significant population declines.

“Many animals are only found in the Southern Ocean, and they all play an important role in its ecosystem,” said Cassandra Brooks, the paper’s senior author and associate professor in the Department of Environmental Studies and a fellow of the ...

Solutions to Nigeria’s newborn mortality rate might lie in existing innovations, finds review

2024-08-15

The review, led by Imperial College London’s Professor Hippolite Amadi, argues that Nigeria’s own discoveries and technological advancements of the past three decades have been “abandoned” by policymakers.

The authors argue that too many Nigerian newborns, clinically defined as infants in the first 28 days of life, die of causes that could have been prevented had policymakers adopted recent in-country scientific breakthroughs.

Led by Professor Amadi of Imperial’s Department of Bioengineering, who received the Nigeria Prize ...

Study highlights sex differences in notified infectious disease cases across Europe

2024-08-15

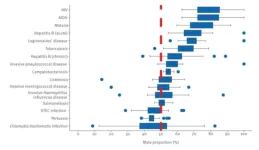

A study published in Eurosurveillance analysing 5.5 million cases of infectious diseases in the European Union/European Economic Area (EU/EEA) over 10 years has found important differences in the relative proportion of notified male versus female cases for several diseases. The proportion of males ranged on average from 40-45% for pertussis and Shiga toxin-producing Escherischia coli (STEC) infections to 75-80% for HIV/AIDS.

“Although this study was not able to fully explain the differences observed across countries and diseases, it offers some interesting leads,” said Julien Beauté, principal expert in general surveillance at the European ...

Nanobody inhibits metastasis of breast tumor cells to lung in mice

2024-08-15

“In the present study we describe the development of an inhibitory nanobody directed against an extracellular epitope present in the native V-ATPase c subunit.”

BUFFALO, NY- August 15, 2024 – A new research paper was published in Oncotarget's Volume 15 on August 14, 2024, entitled, “A nanobody against the V-ATPase c subunit inhibits metastasis of 4T1-12B breast tumor cells to lung in mice.”

The vacuolar H+-ATPase (V-ATPase) is an ATP-dependent proton pump that functions to control the pH of intracellular compartments ...

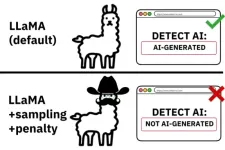

Detecting machine-generated text: An arms race with the advancements of large language models

2024-08-15

Machine-generated text has been fooling humans for the last four years. Since the release of GPT-2 in 2019, large language model (LLM) tools have gotten progressively better at crafting stories, news articles, student essays and more, to the point that humans are often unable to recognize when they are reading text produced by an algorithm. While these LLMs are being used to save time and even boost creativity in ideating and writing, their power can lead to misuse and harmful outcomes, which are already ...

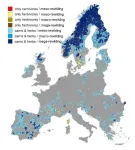

Nearly 25% of European landscape could be rewilded

2024-08-15

Europe's abandoned farmlands could find new life through rewilding, a movement to restore ravaged landscapes to their wilderness before human intervention. A quarter of the European continent, 117 million hectares, is primed with rewilding opportunities, researchers report August 15 in the Cell Press journal Current Biology. They provide a roadmap for countries to meet the 2030 European Biodiversity Strategy's goals to protect 30% of land, with 10% of those areas strictly under conservation.

The team ...