(Press-News.org) Scientists have pinpointed the origin and composition of the asteroid that caused the mass extinction 66 million years ago, revealing it was a rare carbonaceous asteroid from beyond Jupiter, according to a new study. The findings help resolve long-standing debates about the nature of Chicxulub impactor, reshaping our understanding of Earth's history and the extraterrestrial rocks that have collided with it. Earth has experienced several mass extinction events. The most recent event occurred 66 million years ago at the boundary between the Cretaceous and Paleogene eras (K-Pg boundary) and resulted in the loss of roughly 60% of the planet’s species, including non-avian dinosaurs. The Chicxulub impactor, a massive asteroid that collided with Earth in what is now the Gulf of Mexico, is thought to have played a key role in this extinction event. Evidence includes high levels of platinum-group elements (PGEs) like iridium, ruthenium, osmium, rhodium, platinum, and palladium in K-Pg boundary layers, which are rare on Earth but common in meteorites. These elevated PGE levels have been found globally, suggesting the impact spread debris worldwide. While some propose large-scale volcanic activity from the Deccan Traps igneous province as an alternative source of PGEs, the specific PGE ratios at the K-Pg boundary align more with asteroid impacts than volcanic activity. However, much about the nature of the Chicxulub impactor – its composition and extraterrestrial origin – is poorly understood.

To address these questions, Mario Fischer-Gödde and colleagues evaluated ruthenium (Ru) isotopes in samples taken from the K-Pg boundary. For comparison, they also analyzed samples from five other asteroid impacts from the last 541 million years, samples from ancient Archaean-age (3.5 – 3.2 billion-years-old) impact-related spherule layers, and samples from two carbonaceous meteorites. Ficher-Gödde et al. found that the Ru isotope signatures in samples from the K-Pg boundary were uniform and closely matched those of carbonaceous chondrites (CCs), not Earth or other meteorite types, suggesting that the Chicxulub impactor likely came from a C-type asteroid that formed in the outer Solar System. They also rule out a comet as the impactor. Ancient Archean samples also suggest impactors with a CC-like composition, indicating a similar outer Solar System origin and perhaps representing material that impacted during Earth’s final stages of accretion. In contrast, other impact sites from different periods showed Ru isotope compositions consistent with S-type (salicaceous) asteroids from the inner Solar System.

Podcast: A segment of Science's weekly podcast, related to this research, will be available on the Science.org podcast landing page after the embargo lifts. Reporters are free to make use of the segments for broadcast purposes and/or quote from them – with appropriate attribution (i.e., cite "Science podcast"). Please note that the file itself should not be posted to any other Web site.

END

Chicxulub impactor was a carbonaceous-type asteroid from beyond Jupiter

2024-08-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A role for a newly identified brain activity during sleep-dependent memory consolidation

2024-08-15

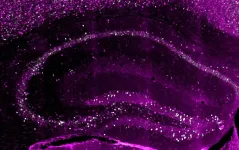

A newly identified activity in the brain that occurs while we sleep – a barrage of action potentials, or a BARR – plays a crucial role in rebalancing the hippocampal neural network during memory consolidation. The findings offer fresh insights into how our brains preserve memories while maintaining stability, as we slumber. Memory consolidation – a process that stabilizes and strengthens our recent experiences into long-term memories – occurs when we sleep. During the non-rapid eye movement (NREM) phase of sleep, ...

Scientists discover superbug's rapid path to antibiotic resistance

2024-08-15

Researchers at the University of Sheffield have discovered how a hospital superbug Clostridioides difficile (C.diff) can rapidly evolve resistance to vancomycin, the frontline drug used in the UK

Scientists found that in less than two months the bacteria could develop resistance to 32 times the initial antibiotic concentration

C.diff, a type of bacteria which often affects people who have been taking antibiotics, has been identified by the World Health Organisation as one of the top global public health threats, and is responsible ...

New technique prints metal oxide thin film circuits at room temperature

2024-08-15

Researchers have demonstrated a technique for printing thin metal oxide films at room temperature, and have used the technique to create transparent, flexible circuits that are both robust and able to function at high temperatures.

“Creating metal oxides that are useful for electronics has traditionally required making use of specialized equipment that is slow, expensive, and operates at high temperatures,” says Michael Dickey, co-corresponding author of a paper on the work and the Camille and Henry Dreyfus Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at North Carolina State University. “We wanted ...

Sleep resets neurons for new memories the next day

2024-08-15

ITHACA, N.Y. – While everyone knows that a good night’s sleep restores energy, a new Cornell University study finds it resets another vital function: memory.

Learning or experiencing new things activates neurons in the hippocampus, a region of the brain vital for memory. Later, while we sleep, those same neurons repeat the same pattern of activity, which is how the brain consolidates those memories that are then stored in a large area called the cortex. But how is it that we can keep learning new things for a lifetime without using up all of our neurons?

A new study, “A Hippocampal Circuit Mechanism ...

Navigating the future: brain cells that plan where to go

2024-08-15

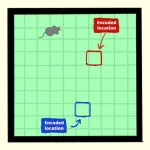

Researchers from the RIKEN Center for Brain Science (CBS) in Japan have discovered a region of the brain that encodes where an animal is planning to be in the near future. Linked to internal maps of spatial locations and past movements, activity in the newly discovered grid cells accurately predicts future locations as an animal travels around its environment. Published in Science on August 15, the study helps explain how planned spatial navigation is possible.

It might seem effortless, but navigating the world requires quite a bit of under-the-hood brain activity. For ...

The brain creates three copies for a single memory

2024-08-15

The ability to turn experiences into memories allows us to learn from the past and use what we learned as a model to respond appropriately to new situations. For this reason, as the world around us changes, this memory model cannot simply be a fixed archive of the good old days. Rather, it must be dynamic, changing over time and adapting to new circumstances to better help us predict the future and select the best course of action. How the brain could regulate a memory’s dynamics was a mystery – until multiple memory copies ...

Breakthrough addresses sex-related weight gain and disease

2024-08-15

ITHACA, N.Y. -- A decline in estrogen during menopause causes changes in body fat distribution and associated cardiovascular and metabolic disease, but a new study identifies potential therapies that might one day reverse these unhealthy shifts.

The study, “Cxcr4 Regulates a Pool of Adipocyte Progenitors and Contributes to Adiposity in a Sex-Dependent Manner,” was published Aug. 5 in Nature Communications.

The researchers discovered that a receptor called Cxcr4, when blocked in mice, reduced the tendency of fat stem cells to develop into white fat, also called white adipose tissue. This treatment could potentially be combined with low doses of estrogen therapy to cut ...

As human activities expand in Antarctica, scientists identify crucial conservation sites

2024-08-15

A team of scientists led by the University of Colorado Boulder has identified 30 new areas critical for conserving biodiversity in the Southern Ocean surrounding Antarctica. In a study published Aug. 15 in the journal Conservation Biology, the researchers warn that without greater protection to limit human activities in these areas, native wildlife could face significant population declines.

“Many animals are only found in the Southern Ocean, and they all play an important role in its ecosystem,” said Cassandra Brooks, the paper’s senior author and associate professor in the Department of Environmental Studies and a fellow of the ...

Solutions to Nigeria’s newborn mortality rate might lie in existing innovations, finds review

2024-08-15

The review, led by Imperial College London’s Professor Hippolite Amadi, argues that Nigeria’s own discoveries and technological advancements of the past three decades have been “abandoned” by policymakers.

The authors argue that too many Nigerian newborns, clinically defined as infants in the first 28 days of life, die of causes that could have been prevented had policymakers adopted recent in-country scientific breakthroughs.

Led by Professor Amadi of Imperial’s Department of Bioengineering, who received the Nigeria Prize ...

Study highlights sex differences in notified infectious disease cases across Europe

2024-08-15

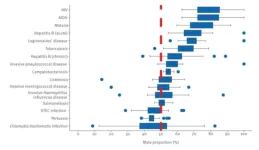

A study published in Eurosurveillance analysing 5.5 million cases of infectious diseases in the European Union/European Economic Area (EU/EEA) over 10 years has found important differences in the relative proportion of notified male versus female cases for several diseases. The proportion of males ranged on average from 40-45% for pertussis and Shiga toxin-producing Escherischia coli (STEC) infections to 75-80% for HIV/AIDS.

“Although this study was not able to fully explain the differences observed across countries and diseases, it offers some interesting leads,” said Julien Beauté, principal expert in general surveillance at the European ...