(Press-News.org) More than 70 genes have been linked to autism spectrum disorder (ASD), a developmental condition in which differences in the brain lead to a host of altered behaviors, including issues with language, social communication, hyperactivity, and repetitive movements. Scientists are attempting to tease out those specific associations gene by gene, neuron by neuron.

One such gene is Astrotactin 2 (ASTN2). In 2018, researchers from the Laboratory of Developmental Neurobiology at Rockefeller University discovered how defects in the protein produced by the gene disrupted circuitry in the cerebellum in children with neurodevelopmental conditions.

Now the same lab has found that knocking out the gene entirely leads to several hallmark behaviors of autism. As they describe in a new paper in PNAS, mice that lacked ASTN2 showed distinctly different behaviors from their wild-type nestmates in four key ways: they vocalized and socialized less but were more hyperactive and repetitive in their behavior.

“All of these traits have parallels in people with ASD,” says Michalina Hanzel, first author of the paper. “Alongside these behaviors, we also found structural and physiological changes in the cerebellum.”

“It’s a big finding in the field of neuroscience,” says lab lead Mary E. Hatten, whose work has focused on this brain region for decades. “It also underscores this emerging story that the cerebellum has cognitive functions that are quite independent of its motor functions.”

An unexpected role

In 2010, Hatten’s lab discovered that proteins produced by the ASTN2 gene help guide neurons as they migrate during the development of cerebellum and form its structure. In the 2018 study, they examined a family in which three children had both neurodevelopmental disorders and ASTN2 mutations. They found that in a developed brain, the proteins have a similar guiding role: they keep the chemical conversation between neurons going by ushering receptors off the neural surfaces to make room for new receptors to rotate in. In a mutated gene, the proteins fail to act and the receptors pile up, resulting in a traffic jam that hinders neuronal connections and communication. This impact could be seen in the children’s afflictions, which included intellectual disability, language delays, ADHD, and autism.

The find was part of a growing body of evidence that the cerebellum—the oldest cortical structure in the brain—is important not just for motor control but also for language, cognition, and social behavior.

For the current study, Hanzel wanted to see what effects a total absence of the ASTN2 gene might have on cerebellar structure and on behavior. Collaborating with study co-authors Zachi Horn, a former postdoc in the Hatten lab, and with assistance from Shiaoching Gong, of Weill Cornell Medicine, Hanzel spent two years creating a knockout mouse that lacked ASTN2, and then studied the brains and activity of both infant and adult mice.

Behavioral parallels

The knockout mice participated in several noninvasive behavioral experiments to see how they compared to their wild-type nestmates. The knockout mice showed distinctly different characteristics in all of them.

In one study, the researchers briefly isolated baby mice, then measured how frequently they called out for their mothers using ultrasonic vocalizations. These sounds are a key part of a mouse’s social behavior and communication, and they’re one of the best proxies researchers have for assessing parallels to human language skills.

The wild-type pups were quick to call for their mothers using complex, pitch-shifting sounds, while the knockout pups gave fewer, shorter calls within a limited pitch range.

Similar communication issues are common in people with ASD, Hanzel says. “It’s one of the most telling characteristics, but it exists along a spectrum,” she says. “Some autistic people don’t understand metaphor, while others echo language they’ve overheard, and still others do not speak at all.”

In another experiment, the researchers tested how ASTN2 mice interacted with both familiar and unfamiliar mice. They preferred to interact with a mouse they knew rather than one they didn’t. In contrast, wild-type mice always choose the social novelty of a new face.

This, too, has parallels in human ASD behavior, with a reluctance towards unfamiliar environments and people being common, Hanzel adds. “That’s a very important result, because it shows that mice with the knockout mutation do not like social novelty and prefer to spend time with mice they know, which corresponds to people with ASD, who tend to like new social interactions less than familiar ones.”

In a third experiment, both types of mice were given free rein to explore an open space for an hour. The ASTN2 mice traveled a significantly longer distance than the other mice, and engaged in repetitive behaviors, such as circling in place, 40% more. Both hyperactivity and repetitive behaviors are well-known hallmarks of ASD.

Miscommunication between brain regions

When they analyzed the brains of the ASTN2 mice, they found a few small but apparently potent structural and physiological changes in the cerebellum. One was that large neurons called Purkinje cells had a higher density of dendritic spines, structures that are spotted with the synapses that send neural signals. But they only detected this change in distinct areas of the cerebellum. “For example, we found the biggest difference in the posterior vermis region, where repetitive and inflexible behaviors are controlled,” Hanzel says.

The scientists also found a decrease in the number of immature dendritic spines known as filopodia and the volume of Bergmann glial fibers, which help with cell migration.

“The differences are quite subtle, but they are clearly affecting how the mice are behaving,” Hatten says. “The changes are probably altering the communication between the cerebellum and the rest of the brain.”

In the future, the researchers plan to study human cerebellar cells, which they’ve been developing for a half-dozen years from stem cells, as well as cells with ASTN2 mutations that were donated by the family in the 2018 study.

“We’d like to see if we can find parallel differences to what we found in mice in human cells,” Hatten says.

She continues, “We also want to look at the detailed biology of other genes that are associated with autism. There are dozens of them, but there’s no agreed-upon commonality that binds them together. We’re very excited that we’ve been able to show in detail what ASTN2 does, but there are a lot more genes to investigate.”

END

Knocking out one key gene leads to autistic traits

2024-08-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

What does the EU's recent AI Act mean in practice?

2024-08-16

The European Union's law on artificial intelligence came into force on 1 August. The new AI Act essentially regulates what artificial intelligence can and cannot do in the EU. A team led by computer science professor Holger Hermanns from Saarland University and law professor Anne Lauber-Rönsberg from Dresden University of Technology has examined how the new legislation impacts the practical work of programmers. The results of their analysis will be published in the autumn.

'The AI Act shows ...

A visionary approach: How an Argonne team developed accessible maps for colorblind scientists

2024-08-16

Imagine having to do your job, but not being able to visually process the data right in front of you. Nearly eight percent of genetic males and half a percent of genetic females have some form of Color Vision Deficiency (CVD), or the decreased ability to discern between particular colors. CVD is commonly referred to as color blindness.

Scientists use colors to convey information. Many scientists in the weather radar community have CVD and the use and interpretation of color is an important aspect of their work. Most colormaps ...

Unveiling the power of hot carriers in plasmonic nanostructures

2024-08-16

A new scientific review explores the exciting potential of hot carriers, energetic electrons generated by light in plasmonic nanostructures. These tiny structures hold immense promise for future technologies due to their unique way of interacting with light and creating hot carriers.

Hot carriers are electrons with a surplus of energy. When light strikes a plasmonic nanostructure, it can excite these electrons, pushing them out of equilibrium. This non-equilibrium state unlocks a range of fascinating phenomena. Hot carriers can be used to control light itself, potentially leading to ...

New research shows agricultural impacts on soil microbiome and fungal communities

2024-08-16

New research from Smithsonian’s Bird Friendly Coffee program highlights a type of biodiversity that often gets overlooked: soil bacteria and fungal communities. For over twenty years, Smithsonian research has shown that coffee farms with shade trees protect more biodiversity than intensified, monoculture coffee farms. The new research, published today in Applied Soil Ecology, shows that soil bacteria and fungi on coffee farms also respond to the intensity of coffee farm management. To conduct this research, the team collected soils samples on coffee farms in Colombia, El Salvador, and Peru and used DNA analysis to profile bacterial and fungal soil on ...

Tracking down the asteroid that sealed the fate of the dinosaurs

2024-08-16

Geoscientists from the University of Cologne have led an international study to determine the origin of the huge piece of rock that hit the Earth around 66 million years ago and permanently changed the climate. The scientists analysed samples of the rock layer that marks the boundary between the Cretaceous and Paleogene periods. This period also saw the last major mass extinction event on Earth, in which around 70 percent of all animal species became extinct. The results of the study published in Science indicate that the asteroid formed outside Jupiter’s orbit during the ...

IOP Publishing hosts Progress In Physics 2024 – a two-day hybrid conference focused on condensed matter physics

2024-08-16

The Institute of Physics and IOP Publishing (IOPP) are launching Progress In Physics 2024, a two-day hybrid workshop hosted at the Institute of Physics’ office in London from 9-10 October 2024. The event will cover topics on condensed matter and will bring together leading physics researchers to exchange knowledge in both an in-person and online format.

Progress in Physics 2024 aligns with the mission of IOPP’s new Progress In seriesTM of journals. The series builds on the success of IOPP’s flagship journal Reports on Progress in PhysicsTM which celebrates its 90th anniversary this year.

With ...

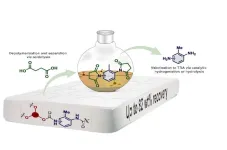

Researchers discover smarter way to recycle polyurethane

2024-08-16

Researchers discover smarter way to recycle polyurethane

Researchers at Aarhus University have found a better method to recycle polyurethane foam from items like mattresses. This is great news for the budding industry that aims to chemically recover the original components of the material – making their products cheaper and better.

Polyurethane (PUR) is an indispensable plastic material used in mattresses, insulation in refrigerators and buildings, shoes, cars, airplanes, wind turbine blades, cables, and much more. It could be called a wonder material if it weren’t also an environmental ...

Right on schedule: Physicists use modeling to forecast a black hole's feeding patterns with precision

2024-08-16

Powerful telescopes like NASA’s Hubble, James Webb, and Chandra X-ray Observatory provide scientists a window into deep space to probe the physics of black holes. While one might wonder how you can “see” a black hole, which famously absorbs all light, this is made possible by tidal disruption events (TDEs) - where a star is destroyed by a supermassive black hole and can fuel a “luminous accretion flare.” With luminosities thousands of billions of times brighter than the Sun, accretion events enable astrophysicists to study supermassive black holes (SMBHs) at cosmological distances.

TDEs occur when a star is violently ripped ...

Cell death types and their relations to host immune pathways

2024-08-16

“We have proposed a framework encompassing all discovered host immunological pathways, such as TH1, TH2a, TH2b, TH3, TH9, TH17, TH22, TH1-like, and THαβ immune reactions”

BUFFALO, NY- August 16, 2024 – A new review was published as the cover paper of Aging (listed by MEDLINE/PubMed as "Aging (Albany NY)" and "Aging-US" by Web of Science), Volume 16, Issue 15, entitled, “Types of cell death and their relations to host immunological pathways”.

Various ...

Perceived parental distraction by technology and mental health among emerging adolescents

2024-08-16

About The Study: In a cohort study of 1,300 emerging adolescents ages 9 to 11 across three assessments, higher levels of anxiety symptoms were associated with higher levels of perceived parental technoference later in development. Higher levels of perceived parental technoference were associated with higher levels of inattention and hyperactivity symptoms later in development. The findings of this study speak to the need to discuss digital technology use and mental health with parents and emerging adolescents as a part of routine care.

Corresponding Author: To contact ...