(Press-News.org) In recent years, the news about Earth's climate—from raging wildfires and stronger hurricanes, to devastating floods and searing heat waves—has provided little good news.

A new Dartmouth-led study, however, reports that one of the very worst projections of how high the world's oceans might rise as the planet's polar ice sheets melt is highly unlikely—though it stresses that the accelerating loss of ice from Greenland and Antarctica is nonetheless dire.

The study challenges a new and alarming prediction in the latest high-profile report from the United Nations' Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to evaluate the latest climate research and project the long- and near-term effects of the climate crisis. Released in full last year, the IPCC's sixth assessment report introduced a possible scenario in which the collapse of the southern continent's ice sheets would make Antarctica's contribution to average global sea level twice as high by 2100 than other models project—and three times as high by 2300.

Though the IPCC designated this specific prediction as "low likelihood," the potential of the world's oceans rising by as much as 50 feet as the model projects earned it a spot in the report. At that magnitude, the Florida Peninsula would be submerged, save for a strip of interior high ground spanning from Gainesville to north of Lake Okeechobee, with the state's coastal cities underwater.

But that prediction is based on a new hypothetical mechanism of how ice sheets—the thick, land-based glaciers covering polar regions—retreat and break apart. The mechanism, known as the Marine Ice Cliff Instability (MICI), has not been observed and has so far only been tested with a single low-resolution model, the researchers report in the journal Science Advances.

The researchers instead test MICI with three high-resolution models that more accurately capture the complex dynamics of ice sheets. They simulated the retreat of Antarctica's Thwaites Glacier, the 75-mile-wide ice sheet popularly nicknamed the "Doomsday Glacier" for the accelerating rate at which it is melting and its potential to raise global sea levels by more than two feet. Their models showed that even the imperiled Thwaites is unlikely to rapidly collapse during the 21st century as MICI would predict.

Mathieu Morlighem, a Dartmouth professor of earth sciences and the paper's corresponding author, said that the findings suggest that the physics underlying the extreme projection included in the IPCC report are inaccurate, which can have real-world effects. Policymakers sometimes use these high-estimation models when considering the construction of physical barriers such as sea walls or even relocating people who live in low-lying areas, Morlighem said.

"These projections are actually changing people's lives. Policymakers and planners rely on these models and they're frequently looking at the high-end risk. They don't want to design solutions and then the threat turns out to be even worse than they thought," Morlighem said.

"We're not reporting that the Antarctic is safe and that sea-level rise isn't going to continue—all of our projections show a rapid retreat of the ice sheet," he continues. "But high-end projections are important for coastal planning and we want them to be accurate in terms of physics. In this case, we know this extreme projection is unlikely over the course of the 21st century."

Morlighem worked with Dartmouth's Hélène Seroussi, associate professor in the Thayer School of Engineering, along with researchers from the University of Michigan, the University of Edinburgh and the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, and Northumbria University and the University of Stirling in England.

The idea behind MICI is that if an ice shelf—the floating extension of the land-based ice sheet—collapses rapidly, it would potentially leave the ice cliffs that form the outer edge of the ice sheet exposed and unsupported. If these cliffs are tall enough, they would break under its own weight, exposing an even taller cliff and leading to rapid retreat as the ice sheet collapses inward toward the interior like a row of dominos. The loss of this ice into the ocean where it would melt is what would lead to the projected dramatic sea-level rise.

But the authors of the Science Advances study find that the glacial collapse is not that simple or that fast. "Everyone agrees that cliff failure is real—a cliff will collapse if it's too tall. The question is how fast that will happen," Morlighem said. "But we found that the rate of retreat is nowhere near as high as what was assumed in these initial simulations. When we use a rate that is better constrained by physics, we see that ice cliff instability never kicks in."

The researchers focused on Thwaites Glacier because it has been identified as especially vulnerable to collapse as its supporting ice shelf continues to break down. The researchers simulated Thwaites' retreat for 100 years following a sudden hypothetical collapse of its ice shelf, as well as for 50 years under the rate of retreat actually underway.

In all their simulations, the researchers found that Thwaites' ice cliffs never retreated inland at the speed MICI suggests. Instead, without the ice shelf holding the ice sheet back, the movement of the glacier toward the ocean accelerates rapidly, causing the ice sheet to expand away from the interior. This accelerated movement also thins the ice at the glacier's edge, which reduces the height of the ice cliffs and their susceptibility to collapse.

"We're not calling into question the standard, well-established projections that the IPCC's report is primarily based on," Seroussi said. "We're only calling into question this high-impact, low-likelihood projection that includes this new MICI process that is poorly understood. Other known instabilities in the polar ice sheets are still going to play a role in their loss in the coming decades and centuries."

Polar ice sheets are, for example, vulnerable to the established Marine Ice Sheet Instability (MISI), said study coauthor Dan Goldberg, a glaciologist at Edinburgh who was a visiting professor at Dartmouth when the project began. MISI predicts that, without the protection of ice shelves, a glacier resting on a submerged continent that slopes downward toward the interior of the ice sheet will retreat unstably. This process is expected to accelerate ice loss and contribute increasingly to sea-level rise, Goldberg said.

"While we did not observe MICI in the 21st century, this was in part because of processes that can lead to the MISI," Goldberg said. "In any case, Thwaites is likely to retreat unstably in the coming centuries, which underscores the need to better understand how the glacier will respond to ocean warming and ice-shelf collapse through ongoing modeling and observation."

The paper, "The West Antarctic Ice Sheet may not be vulnerable to Marine Ice Cliff Instability during the 21st Century," was published in Science Advances on Aug. 21, 2024. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (grant no. 1739031) and Natural Environment Research Council (grant nos. NE/S006745/1 and NE/S006796/1).

END

Study finds highest prediction of sea-level rise unlikely

Researchers question model of rapid polar ice collapse, but say retreat is still dire.

2024-08-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New study reveals devastating power and colossal extent of a giant underwater avalanche off the Moroccan coast

2024-08-21

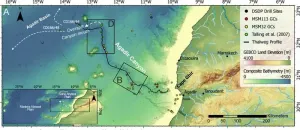

New research by the University of Liverpool has revealed how an underwater avalanche grew more than 100 times in size causing a huge trail of destruction as it travelled 2000km across the Atlantic Ocean seafloor off the North West coast of Africa.

In a study publishing in the journal Science Advances (and featured on the front cover), researchers provide an unprecedented insight into the scale, force and impact of one of nature’s mysterious phenomena, underwater avalanches.

Dr Chris Stevenson, a sedimentologist from the University of Liverpool’s School of Environmental Sciences, co-led the team that for the first time has mapped a giant underwater avalanche from head ...

To kill mammoths in the Ice Age, people used planted pikes, not throwing spears, researchers say

2024-08-21

How did early humans use sharpened rocks to bring down megafauna 13,000 years ago? Did they throw spears tipped with carefully crafted, razor-sharp rocks called Clovis points? Did they surround and jab mammoths and mastadons? Or did they scavenge wounded animals, using Clovis points as a versatile tool to harvest meat and bones for food and supplies?

UC Berkeley archaeologists say the answer might be none of the above.

Instead, researchers say humans may have braced the butt of their pointed spears against the ground and angled the weapon upward in a way that would impale a charging animal. The force would have driven the spear deeper ...

Using AI to link heat waves to global warming

2024-08-21

Researchers at Stanford and Colorado State University have developed a rapid, low-cost approach for studying how individual extreme weather events have been affected by global warming. Their method, detailed in a Aug. 21 study in Science Advances, uses machine learning to determine how much global warming has contributed to heat waves in the U.S. and elsewhere in recent years. The approach proved highly accurate and could change how scientists study and predict the impact of climate change on a range of extreme weather events. The ...

The role of an energy-producing enzyme in treating Parkinson’s disease

2024-08-21

An enzyme called PGK1 has an unexpectedly critical role in the production of chemical energy in brain cells, according to a preclinical study led by researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine. The investigators found that boosting its activity may help the brain resist the energy deficits that can lead to Parkinson’s disease.

The study, published Aug. 21 in Science Advances, presented evidence that PGK1 is a “rate-limiting” enzyme in energy production in the output-signaling branches, or axons, of the dopamine neurons that are affected in Parkinson’s disease. This means that even a modest boost to PGK1 activity can have ...

Life from a drop of rain: New research suggests rainwater helped form the first protocell walls

2024-08-21

One of the major unanswered questions about the origin of life is how droplets of RNA floating around the primordial soup turned into the membrane-protected packets of life we call cells.

A new paper by engineers from the University of Chicago’s Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (UChicago PME), the University of Houston’s Chemical Engineering Department, and biologists from the UChicago Chemistry Department, have proposed a solution.

In the paper, published today in Science Advances, UChicago PME postdoctoral researcher Aman Agrawal and his co-authors ...

Surprising mechanism for removing dead cells identified

2024-08-21

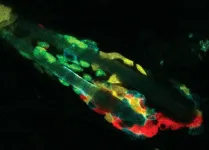

Billions of our cells die every day to make way for the growth of new ones. Most of these goners are cleaned up by phagocytes—mobile immune cells that migrate where needed to engulf problematic substances. But some dying or dead cells are consumed by their own neighbors, natural tissue cells with other primary jobs. How these cells sense the dying or dead around them has been largely unknown.

Now researchers from The Rockefeller University have shown how the sensor system operates in hair follicles, which have a well-known cycle of birth, decay, and regeneration put into motion by hair follicle stem cells (HFSCs). In a new study published in Nature, ...

UC Irvine discovery of ‘item memory’ brain cells offers new Alzheimer’s treatment target

2024-08-21

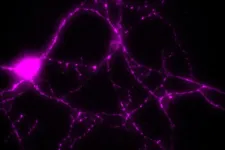

Irvine, Calif., Aug. 21, 2024 — Researchers from the University of California, Irvine have discovered the neurons responsible for “item memory,” deepening our understanding of how the brain stores and retrieves the details of “what” happened and offering a new target for treating Alzheimer’s disease.

Memories include three types of details: spatial, temporal and item, the “where, when and what” of an event. Their creation is a complex process that involves storing information based on the meanings and outcomes of different experiences and forms the foundation of our ability to recall and recount them.

The study, published ...

Study shows successful use of ChatGPT in ag education

2024-08-21

By John Lovett

University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. — Artificial intelligence tools such as ChatGPT show promise as a useful means in agriculture to write simple computer programs for microcontrollers, according to a study published this month.

Microcontrollers are small computers that can perform tasks based on custom computer programs. They receive inputs from sensors and can be used in climate and irrigation controls, food processing systems, as well as robotic and drone applications, to name a few agricultural uses.

A recent study published with the Arkansas Agricultural ...

Early interventions may improve long-term academic achievement in young childhood brain tumor survivors

2024-08-21

(MEMPHIS, Tenn. – August 20, 2024) Children who survive a brain tumor often experience effects from both the cancer and its treatment long after therapy concludes. Scientists at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital found very young children treated for brain tumors were less prepared for school (represented by lower academic readiness scores) compared to their peers. This gap persisted once survivors entered formal schooling. Children from families of higher socioeconomic status were partially protected from the effect, suggesting that providing early developmental resources may proactively help reduce the academic achievement gap. The findings were published today in ...

Cholecystectomy not always necessary for gallstones and abdominal pain

2024-08-21

Each year, 100,000 people visit their doctor with abdominal pain, with approximately 30,000 of them diagnosed with gallstones. The standard treatment for these patients is a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Since the 1990s, the number of surgeries has increased exponentially, despite the lack of clear international criteria. As a result, gallbladder removal is one of the most common surgeries in the Netherlands, yet it is not always effective against pain: about one-third of patients continue to experience abdominal pain after cholecystectomy. The procedure has long been an example of inappropriate care, but this is now changing.

In a 2019 study conducted by Radboud university ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

FAU Harbor Branch awarded $900,000 for Gulf of America sea-level research

Terminal ileum intubation and biopsy in routine colonoscopy practice

Researchers find important clue to healthy heartbeats

Characteristic genomic and clinicopathologic landscape of DNA polymerase epsilon mutant colorectal adenocarcinomas

Start school later, sleep longer, learn better

Many nations underestimate greenhouse emissions from wastewater systems, but the lapse is fixable

The Lancet: New weight loss pill leads to greater blood sugar control and weight loss for people with diabetes than current oral GLP-1, phase 3 trial finds

Pediatric investigation study highlights two-way association between teen fitness and confidence

Researchers develop cognitive tool kit enabling early Alzheimer's detection in Mandarin Chinese

New book captures hidden toll of immigration enforcement on families

New record: Laser cuts bone deeper than before

Heart attack deaths rose between 2011 and 2022 among adults younger than age 55

Will melting glaciers slow climate change? A prevailing theory is on shaky ground

New treatment may dramatically improve survival for those with deadly brain cancer

Here we grow: chondrocytes’ behavior reveals novel targets for bone growth disorders

Leaping puddles create new rules for water physics

Scientists identify key protein that stops malaria parasite growth

Wildfire smoke linked to rise in violent assaults, new 11-year study finds

New technology could use sunlight to break down ‘forever chemicals’

Green hydrogen without forever chemicals and iridium

Billion-DKK grant for research in green transformation of the built environment

For solar power to truly provide affordable energy access, we need to deploy it better

Middle-aged men are most vulnerable to faster aging due to ‘forever chemicals’

Starving cancer: Nutrient deprivation effects on synovial sarcoma

Speaking from the heart: Study identifies key concerns of parenting with an early-onset cardiovascular condition

From the Late Bronze Age to today - Old Irish Goat carries 3,000 years of Irish history

Emerging class of antibiotics to tackle global tuberculosis crisis

Researchers create distortion-resistant energy materials to improve lithium-ion batteries

Scientists create the most detailed molecular map to date of the developing Down syndrome brain

Nutrient uptake gets to the root of roots

[Press-News.org] Study finds highest prediction of sea-level rise unlikelyResearchers question model of rapid polar ice collapse, but say retreat is still dire.