(Press-News.org) One of the major unanswered questions about the origin of life is how droplets of RNA floating around the primordial soup turned into the membrane-protected packets of life we call cells.

A new paper by engineers from the University of Chicago’s Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (UChicago PME), the University of Houston’s Chemical Engineering Department, and biologists from the UChicago Chemistry Department, have proposed a solution.

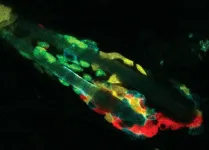

In the paper, published today in Science Advances, UChicago PME postdoctoral researcher Aman Agrawal and his co-authors – including UChicago PME Dean Emeritus Matthew Tirrell and Nobel Prize-winning biologist Jack Szostak – show how rainwater could have helped create a meshy wall around protocells 3.8 billion years ago, a critical step in the transition from tiny beads of RNA to every bacterium, plant, animal, and human that ever lived.

“This is a distinctive and novel observation,” Tirrell said.

The research looks at “coacervate droplets” – naturally occurring compartments of complex molecules like proteins, lipids, and RNA. The droplets, which behave like drops of cooking oil in water, have long been eyed as a candidate for the first protocells. But there was a problem. It wasn’t that these droplets couldn’t exchange molecules between each other, a key step in evolution, the problem was that they did it too well, and too fast.

Any droplet containing a new, potentially useful pre-life mutation of RNA would exchange this RNA with the other RNA droplets within minutes, meaning they would quickly all be the same. There would be no differentiation and no competition – meaning no evolution.

And that means no life.

“If molecules continually exchange between droplets or between cells, then all the cells after a short while will look alike, and there will be no evolution because you are ending up with identical clones,” Agrawal said.

Engineering a solution

Life is by nature interdisciplinary, so Szostak, the director of UChicago’s Chicago Center for the Origins of Life, said it was natural to collaborate with both UChicago PME, UChicago’s interdisciplinary school of molecular engineering, and the chemical engineering department at the University of Houston.

“Engineers have been studying the physical chemistry of these types of complexes – and polymer chemistry more generally – for a long time. It makes sense that there's expertise in the engineering school,” Szostak said. “When we're looking at something like the origin of life, it's so complicated and there are so many parts that we need people to get involved who have any kind of relevant experience.”

In the early 2000s, Szostak started looking at RNA as the first biological material to develop. It solved a problem that had long stymied researchers looking at DNA or proteins as the earliest molecules of life.

“It's like a chicken-egg problem. What came first?” Agrawal said. “DNA is the molecule which encodes information, but it cannot do any function. Proteins are the molecules which perform functions, but they don't encode any heritable information.”

Researchers like Szostak theorized that RNA came first, “taking care of everything” in Agrawal’s words, with proteins and DNA slowly evolving from it.

“RNA is a molecule which, like DNA, can encode information, but it also folds like proteins so that it can perform functions such as catalysis as well,” Agrawal said.

RNA was a likely candidate for the first biological material. Coacervate droplets were likely candidates for the first protocells. Coacervate droplets containing early forms of RNA seemed a natural next step.

That is until Szostak poured cold water on this theory, publishing a paper in 2014 showing that RNA in coacervate droplets exchanged too rapidly.

“You can make all kinds of droplets of different types of coacervates, but they don't maintain their separate identity. They tend to exchange their RNA content too rapidly. That’s been a long-standing problem,” Szostak said. “What we showed in this new paper is that you can overcome at least part of that problem by transferring these coacervate droplets into distilled water – for example, rainwater or freshwater of any type – and they get a sort of tough skin around the droplets that restricts them from exchanging RNA content.”

‘A spontaneous combustion of ideas’

Agrawal started transferring coacervate droplets into distilled water during his PhD research at the University of Houston, studying their behavior under an electric field. At this point, the research had nothing to do with the origin of life, just studying the fascinating material from an engineering perspective.

“Engineers, particularly Chemical and Materials, have good knowledge of how to manipulate material properties such as interfacial tension, role of charged polymers, salt, pH control, etc.,” said University of Houston Prof. Alamgir Karim, Agrawal’s former thesis advisor and a senior co-author of the new paper. “These are all key aspects of the world popularly known as ‘complex fluids’ - think shampoo and liquid soap.”

Agrawal wanted to study other fundamental properties of coacervates during his PhD. It wasn’t Karim’s area of study, but Karim had worked decades earlier at the University of Minnesota under one of the world’s top experts – Tirrell, who later became founding dean of the UChicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering.

During a lunch with Agrawal and Karim, Tirrell brought up how the research into the effects of distilled water on coacervate droplets might relate to the origin of life on Earth. Tirrell asked where distilled water would have existed 3.8 billion years ago.

“I spontaneously said ‘rainwater!’ His eyes lit up and he was very excited at the suggestion,” Karim said. “So, you can say it was a spontaneous combustion of ideas or ideation!”

Tirrell brought Agrawal’s distilled water research to Szostak, who had recently joined the University of Chicago to lead what was then called the Origins of Life Initiative. He posed the same question he had asked Karim.

“I said to him, ‘Where do you think distilled water could come from in a prebiotic world?’” Tirrell recalled. “And Jack said exactly what I hoped he would say, which was rain.”

Working with RNA samples from Szostak, Agrawal found that transferring coacervate droplets into distilled water increased the time scale of RNA exchange – from mere minutes to several days. This was long enough for mutation, competition, and evolution.

“If you have protocell populations that are unstable, they will exchange their genetic material with each other and become clones. There is no possibility of Darwinian evolution,” Agrawal said. “But if they stabilize against exchange so that they store their genetic information well enough, at least for several days so that the mutations can happen in their genetic sequences, then a population can evolve.”

Rain, checked

Initially, Agrawal experimented with deionized water, which is purified under lab conditions. “This prompted the reviewers of the journal who then asked what would happen if the prebiotic rainwater was very acidic,” he said.

Commercial lab water is free from all contaminants, has no salt, and lives with a neutral pH perfectly balanced between base and acid. In short, it’s about as far from real-world conditions as a material can get. They needed to work with a material more like actual rain.

What’s more like rain than rain?

“We simply collected water from rain in Houston and tested the stability of our droplets in it, just to make sure what we are reporting is accurate,” Agrawal said.

In tests with the actual rainwater and with lab water modified to mimic the acidity of rainwater, they found the same results. The meshy walls formed, creating the conditions that could have led to life.

The chemical composition of the rain falling over Houston in the 2020s is not the rain that would have fallen 750 million years after the Earth formed, and the same can be said for the model protocell system Agrawal tested. The new paper proves that this approach of building a meshy wall around protocells is possible and can work together to compartmentalize the molecules of life, putting researchers closer than ever to finding the right set of chemical and environmental conditions that allow protocells to evolve.

“The molecules we used to build these protocells are just models until more suitable molecules can be found as substitutes,” Agrawal said. “While the chemistry would be a little bit different, the physics will remain the same.”

Citation: “Did the exposure of coacervate droplets to rain make them the first stable protocells?” Agrawal et al, Science Advances, August 21, 2024. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adn9657

END

Life from a drop of rain: New research suggests rainwater helped form the first protocell walls

A Nobel-winning biologist, two engineering schools, and a vial of Houston rainwater cast new light on the origin of life on Earth

2024-08-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Surprising mechanism for removing dead cells identified

2024-08-21

Billions of our cells die every day to make way for the growth of new ones. Most of these goners are cleaned up by phagocytes—mobile immune cells that migrate where needed to engulf problematic substances. But some dying or dead cells are consumed by their own neighbors, natural tissue cells with other primary jobs. How these cells sense the dying or dead around them has been largely unknown.

Now researchers from The Rockefeller University have shown how the sensor system operates in hair follicles, which have a well-known cycle of birth, decay, and regeneration put into motion by hair follicle stem cells (HFSCs). In a new study published in Nature, ...

UC Irvine discovery of ‘item memory’ brain cells offers new Alzheimer’s treatment target

2024-08-21

Irvine, Calif., Aug. 21, 2024 — Researchers from the University of California, Irvine have discovered the neurons responsible for “item memory,” deepening our understanding of how the brain stores and retrieves the details of “what” happened and offering a new target for treating Alzheimer’s disease.

Memories include three types of details: spatial, temporal and item, the “where, when and what” of an event. Their creation is a complex process that involves storing information based on the meanings and outcomes of different experiences and forms the foundation of our ability to recall and recount them.

The study, published ...

Study shows successful use of ChatGPT in ag education

2024-08-21

By John Lovett

University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. — Artificial intelligence tools such as ChatGPT show promise as a useful means in agriculture to write simple computer programs for microcontrollers, according to a study published this month.

Microcontrollers are small computers that can perform tasks based on custom computer programs. They receive inputs from sensors and can be used in climate and irrigation controls, food processing systems, as well as robotic and drone applications, to name a few agricultural uses.

A recent study published with the Arkansas Agricultural ...

Early interventions may improve long-term academic achievement in young childhood brain tumor survivors

2024-08-21

(MEMPHIS, Tenn. – August 20, 2024) Children who survive a brain tumor often experience effects from both the cancer and its treatment long after therapy concludes. Scientists at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital found very young children treated for brain tumors were less prepared for school (represented by lower academic readiness scores) compared to their peers. This gap persisted once survivors entered formal schooling. Children from families of higher socioeconomic status were partially protected from the effect, suggesting that providing early developmental resources may proactively help reduce the academic achievement gap. The findings were published today in ...

Cholecystectomy not always necessary for gallstones and abdominal pain

2024-08-21

Each year, 100,000 people visit their doctor with abdominal pain, with approximately 30,000 of them diagnosed with gallstones. The standard treatment for these patients is a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Since the 1990s, the number of surgeries has increased exponentially, despite the lack of clear international criteria. As a result, gallbladder removal is one of the most common surgeries in the Netherlands, yet it is not always effective against pain: about one-third of patients continue to experience abdominal pain after cholecystectomy. The procedure has long been an example of inappropriate care, but this is now changing.

In a 2019 study conducted by Radboud university ...

Greenhouse gas HFC-23: Abatement of emissions is achievable

2024-08-21

Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) are potent greenhouse gases (GHGs). The most potent of these compounds is trifluoromethane, also known as HFC-23. One kilogram of HFC-23 in the atmosphere contributes as much to the greenhouse effect as 12,000 kilograms of CO₂. It takes around 200 years for the gas to break down in the atmosphere. For this reason, more than 150 countries have committed to significantly reducing their emissions of HFC-23 as part of the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol.

The main source of HFC-23 ...

Researchers identify most common long COVID symptoms in children and teens

2024-08-21

Aug. 21, 2024--Researchers from the NIH’s RECOVER Initiative have determined what long COVID looks like in youths, based on the most common symptoms reported in a study of over 5,300 school-age children and adolescents.

Using the findings, published today in the Journal of the American Medical Association, the researchers also created indices that contain prolonged symptoms—eight for school-age children and 10 for adolescents—that together most likely indicate long COVID.

The indices are not intended to be used in making a clinical diagnosis of long COVID but will guide research to improve diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of the condition in youths.

“Many ...

NIH-funded study finds long COVID affects adolescents differently than younger children

2024-08-21

NIH-funded study finds long COVID affects adolescents differently than younger children Adolescents were most likely to experience low energy/tiredness while children were most likely to report headache

Scientists investigating long COVID in youth found similar but distinguishable patterns between school-age children (ages 6-11 years) and adolescents (ages 12-17 years) and identified their most common symptoms. The study, supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and published in JAMA, comes from research conducted through the NIH’s Researching ...

Characterizing long COVID in children and adolescents

2024-08-21

About The Study: In this large-scale study, symptoms that characterized pediatric postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), or long COVID, differed by age group, and several distinct phenotypic PASC presentations were described. The research indices developed here will help researchers identify children and adolescents with high likelihood of PASC. Although these indices will require further research and validation, this work provides an important step toward a clinically useful tool for diagnosis with the ultimate goal of supporting optimal care for youth with PASC.

Quote from corresponding author Rachel ...

Researchers aim to pull back the curtain on long COVID in kids

2024-08-21

The kids were correct all along.

In the most comprehensive national study since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, a team of researchers that includes a Rutgers-organized consortium of pediatric sites has concluded that long COVID symptoms in children are tangible, pervasive, wide ranging and clinically distinct within specific age groups.

Results of the study, funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), are published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

“We have convincing evidence that COVID-19 is not just a mild, benign illness for children,” ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

[Press-News.org] Life from a drop of rain: New research suggests rainwater helped form the first protocell wallsA Nobel-winning biologist, two engineering schools, and a vial of Houston rainwater cast new light on the origin of life on Earth