One of these key microscale processes is the dietary preferences of bacteria that feed on organic molecules called lipids, according to a journal article, "Microbial dietary preference and interactions affect the export of lipids to the deep ocean," published in Science.

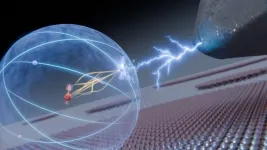

"In our study, we found incredible variation in what the different microbes preferred to digest. Bacteria seem to have very distinct diet preferences for different lipid molecules. This has real implications for understanding carbon sequestration and the biological carbon pump," said journal article co-author Benjamin Van Mooy, a senior scientist in the Marine Chemistry and Geochemistry Department at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). "This study used state-of-the-art methods to link the molecular composition of the sinking biomass with its rates of degradation, which we were able to link to the dietary preferences of bacteria." The biological carbon pump is a process where biomass sinks from the ocean surface to the deep ocean.

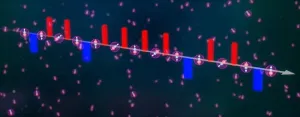

About 5 to 30% of surface ocean particulate organic matter is composed of lipids, which are carbon-rich fatty acid biomolecules that microbes use for energy storage and cellular functions. As the organic matter sinks to the deep sea, diverse communities of resident microbes degrade and make use of the lipids, exerting an important control on global CO2 concentrations. Understanding this process is vital to improve our ability to forecast global carbon fluxes in changing ocean regimes. Geographic areas where more lipids reach the deep ocean undegraded could be hotspots for natural carbon sequestration.

"Bacteria isolated from marine particles exhibited distinct dietary preferences, ranging from selective to promiscuous degraders," the article states. “Using synthetic communities composed of isolates with distinct dietary preferences, we showed that lipid degradation is modulated by microbial interactions. A particle export model incorporating these dynamics indicates that metabolic specialization and community dynamics may influence lipid transport efficiency in the ocean's mesopelagic zone." The mesopelagic zone extends about 200-1000 meters below the ocean surface.

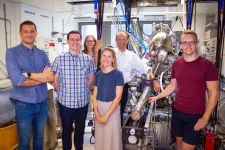

"I was thrilled to see how much there is to learn about the functioning of the ocean by combining two technologies– high-end chemical analysis and microscale imaging–that have historically never been used together", said co-author Roman Stocker, professor at the Institute of Environment Engineering, Department of Civil, Environmental and Geomatic Engineering, ETH Zurich, Switzerland, "I believe that work at the interface between the exciting technologies we now have available in microbial oceanography will continue to yield important insights into how microbes shape our oceans, now and into the future."

“Scientists are starting to understand that lipids in the ocean can vary significantly depending on different environments, such as the coast versus the open ocean, and the season,” said Van Mooy. “With this information, researchers can start to consider whether there are places in the ocean where lipids sink and are sequestered very efficiently, while there may be other locations where lipids are barely sequestered at all or are very inefficiently sequestered.”

"What excites me about this paper is that it shows bacteria are not just eating any type of lipid, but are very specialized and, like us, have specific food preferences," said article co-author Lars Behrendt, associate professor and SciLifeLab fellow at the Science for Life Laboratory, Department of Organismal Biology, Uppsala University, Sweden. "This changes how we think about how microorganisms consume food in their natural environment and how they might help each other or compete for the same resource. It also supports the idea that combinations of bacteria better break down specific compounds, including lipids, or to achieve other desired functions."

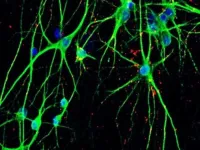

In addition to studying specific bacteria species in isolation, the researchers also looked at how dietary preference affects degradation rates by multispecies communities of bacteria, which they stated is ecologically more relevant than species in isolation. The researchers found that simple synthetic co-cultures exhibited different degradation rates and delay times when compared to monocultures. The researchers also noted that the degradation of particulate organic matter in the natural environment is even more complex than what is described in the study.

“Phytoplankton are the main reason the ocean is one of the biggest carbon sinks. These microscopic organisms play a huge role in the world's carbon cycle - absorbing about as much carbon as all the plants on land combined,” said co-author Uria Alcolombri, senior lecturer, Alexander Silberman Institute of Life Sciences, Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel. "It's fascinating that we can study tiny microbial processes under the microscope while uncovering the biological factors that regulate this massive 'digestive system' of the ocean."

Major funding for this research was provided by the Moore Foundation, Simons Foundation, and National Science Foundation. Additional support was provided by the European Molecular Biology Organization, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Canada Foundation for Innovation, Human Frontier Science Program, Canada Research Chair from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, Independent Research Fund Denmark, Swedish Research Council, Science for Life Laboratory, European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme, and Swiss National Science Foundation.

###

Authors: Lars Behrendt1*#, Uria Alcolombri2#, Jonathan E. Hunter3#, Steven Smriga4, Tracy Mincer5, Daniel P. Lowenstein3, Yutaka Yawata6, François J. Peaudecerf4,7, Vicente I. Fernandez4, Helen F. Fredricks3, Henrik Almblad8, Joe J. Harrison8, Roman Stocker4*, Benjamin A. S. Van Mooy3*

Affiliations:

1Department of Organismal Biology, Science for Life Laboratory, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

2Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences, Institute of Life Sciences, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel

3Department of Marine Chemistry and Geochemistry, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA, USA

4 Institute of Environmental Engineering, Department of Civil, Environmental and Geomatic Engineering, Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich (ETHZ), Zürich, Switzerland

5Florida Atlantic University, Wilkes Honors College, Jupiter, FL, USA

6Faculty of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Japan

7University of Rennes, CNRS, Institut de Physique de Rennes, Rennes, France

8Department of Biological Sciences, University of Calgary, 2500 University Drive NW, Calgary, AB, Canada

#These authors contributed equally

*Corresponding authors

About Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) is a private, non-profit organization on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, dedicated to marine research, engineering, and higher education. Established in 1930, its primary mission is to understand the ocean and its interaction with the Earth as a whole, and to communicate an understanding of the ocean's role in the changing global environment. WHOI's pioneering discoveries stem from an ideal combination of science and engineering—one that has made it one of the most trusted and technically advanced leaders in basic and applied ocean research and exploration anywhere. WHOI is known for its multidisciplinary approach, superior ship operations, and unparalleled deep-sea robotics capabilities. We play a leading role in ocean observation and operate the most extensive suite of data-gathering platforms in the world. Top scientists, engineers, and students collaborate on more than 800 concurrent projects worldwide—both above and below the waves—pushing the boundaries of knowledge and possibility. For more information, please visit www.whoi.edu

Key takeaways:

• The movement of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the surface of the ocean, where it is in active contact with the atmosphere, to the deep ocean, where it can be sequestered away for decades, centuries, or longer, depends on a number of seemingly small processes.

• A key microscale process in the ocean is the dietary preferences of bacteria that feed on organic molecules called lipids, according to a journal article, "Microbial dietary preference and interactions affect the export of lipids to the deep ocean," published in Science.

• "We found incredible variation in what the different microbes preferred to digest. Bacteria seem to have very distinct diet preferences for different lipid molecules. This has real implications for understanding carbon sequestration and the biological carbon pump," said journal article co-author Benjamin Van Mooy, a senior scientist in the Marine Chemistry and Geochemistry Department at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

• "This study uses state-of-the-art methods to link the molecular composition of the sinking biomass with its rates of degradation, and linking that to the preferences of bacteria," said WHOI's Benjamin Van Mooy.

• About 5 to 30% of surface ocean particulate organic matter is composed of lipids, which are carbon-rich fatty acid biomolecules that microbes use for energy storage and cellular functions. As the organic matter sinks to the deep sea, diverse communities of resident microbes degrade and make use the lipids, exerting an important control on global CO2 concentrations. Understanding this process is important to improve our ability to forecast global carbon fluxes in changing ocean regimes. Areas where more lipids reach the deep ocean undegraded could lead to greater rates of carbon sequestration.

END