(Press-News.org) Some of the most dramatic climatic events in our planet’s history are “Snowball Earth” events that happened hundreds of millions of years ago, when almost the entire planet was encased in ice up to 0.6 miles (1 kilometer) thick.

These “Snowball Earth” events have happened only a handful of times and do not occur on regular cycles. Each lasts for millions of years or tens of millions of years and is followed by dramatic warming, but the details of these transitions are poorly understood.

New research from the University of Washington provides a more complete picture for how the last Snowball Earth ended, and suggests why it preceded a dramatic expansion of life on Earth, including the emergence of the first animals.

The study recently published in Nature Communications focuses on ancient rocks known as “cap carbonates,” thought to have formed as the glacial ice thawed. These rocks preserve clues to Earth’s atmosphere and oceans about 640 million years ago, far earlier than what ice cores or tree rings can record.

“Cap carbonates contain information about key properties of Earth's atmosphere and ocean, such as changing levels of carbon dioxide in the air, or the acidity of the ocean,” said lead author Trent Thomas, a UW doctoral student in Earth and space sciences. “Our theory now shows how these properties changed during and after Snowball Earth.”

Cap carbonates are layered limestone or dolomite rocks that have a distinct chemical makeup and today are found in over 50 global locations, including Death Valley, Namibia, Siberia, Ireland and Australia. These rocks are thought to have formed as the Earth-encircling ice sheets melted, causing dramatic changes in atmospheric and ocean chemistry and depositing this unique type of sediment onto the ocean floor.

They are called “caps” because they are the caps above glacial deposits left after Snowball Earth, and “carbonates” because both limestone and dolomite are carbon-containing rocks. Understanding their formation helps explain the carbon cycle during periods of dramatic climate change. The new study, which models the environmental changes, also provides hints about the evolution of life on Earth and why more complex lifeforms followed the last Snowball Earth.

“Life on Earth was simple — in the form of microbes, algae or other tiny aquatic organisms — for over 2 billion years leading up to Snowball Earth,” said senior author David Catling, a UW professor of Earth and space sciences. “In fact, the billion years leading up to Snowball Earth are called the ‘boring billion’ because so little happened. Then two Snowball Earth events occurred. And soon after, animals appear in the fossil record.”

The new paper provides a framework for how the last two facts may be connected.

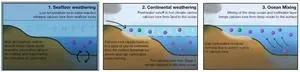

The study modeled chemistry and geology during three phases of Snowball Earth. First, during Snowball Earth’s peak, thick ice encircling the planet reflected sunlight, but some areas of open water allowed exchange between the ocean and atmosphere. Meanwhile frigid seawater continued to react with the ocean floor.

Eventually, carbon dioxide built up in the atmosphere to the point where it trapped enough solar energy to raise global temperatures and melt the ice. This let rainfall reach the Earth, and let freshwater flow into the ocean to join a layer of glacial meltwater that floated over the denser, salty ocean water. This layered ocean slowed down ocean circulation. Later, ocean churning picked up, and mixing between the atmosphere, upper ocean, and deep ocean resumed.

“We predict important changes in the environment as Earth recovered from the Snowball period, some of which affected the temperature, acidity and circulation of the ocean. Now that we know these changes, we can more confidently figure out how they affected Earth’s life,” Thomas said.

Future research will explore how pockets of life that may have survived the tumult of the Snowball Earth and its aftermath could have evolved into the more complex lifeforms that followed soon after.

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation and NASA, in part by a NASA Astrobiology Program grant to the UW’s Virtual Planetary Laboratory.

For more information, contact Thomas at tbthomas@uw.edu or Catling at dcatling@uw.edu.

END

Explaining dramatic planetwide changes after world’s last ‘Snowball Earth’ event

2024-09-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Cleveland Clinic study is first to show success in treating rare blood disorder

2024-09-18

Wednesday, September 18, 2024, CLEVELAND: A clinical trial has demonstrated that the cancer drug pomalidomide is safe and effective in treating hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), a rare bleeding disorder that impacts more than 1 in 5,000 people worldwide. The trial, led by Keith McCrae, M.D., of Cleveland Clinic and supported by the National Institutes of Health, was stopped early because of these successful findings, and has been published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The impetus for this trial was a single patient. About ...

Bone marrow cancer drug shows success in treatment of rare blood disorder

2024-09-18

A clinical trial supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) was stopped early after researchers found sufficient evidence that a drug used to treat bone marrow cancer and Kaposi sarcoma is safe and effective in treating hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), a rare bleeding disorder that affects 1 in 5,000 people worldwide. The trial results, which are published in the New England Journal of Medicine, detail how patients with HHT given the drug, called pomalidomide, experienced a significant reduction in the severity of nosebleeds, needed fewer of the blood transfusions and iron infusions that HHT often demands, ...

Clinical trial successfully repurposes cancer drug for hereditary bleeding disorder

2024-09-18

A drug approved for treating the blood cancer multiple myeloma may offer a safe and effective way to reduce the risk of severe nosebleeds from a rare but devastating bleeding disorder. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), the world's second-most-common inherited bleeding disorder, affects approximately 1-in-5,000 people and can have life-threatening complications, but there are currently no U.S. FDA-approved drugs to treat HHT. The PATH-HHT study, the first-ever randomized, placebo-controlled ...

UVA Engineering professor awarded $1.6M EPA grant to reduce PFAS accumulation in crops

2024-09-18

Associate professor of chemical engineering Bryan Berger received funding from the Environmental Protection Agency to reduce the impact of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, known as PFAS, in food and farming communities.

The award is part of the over $15 million the EPA granted to 10 institutions for PFAS reduction research, aimed at improving farm viability and increasing knowledge of PFAS accumulation.

Water sample collection for testing in Limestone, Maine. (Contributed photo)

Known as forever chemicals, PFAS are man-made substances that have been used in industry ...

UVA professor receives OpenAI grant to inform next-generation AI systems

2024-09-18

Superintelligence — AI systems that surpass human intelligence — could be just a decade away, raising urgent questions about how to ensure their safety and alignment with human values, according to OpenAI.

These AI systems could be hugely beneficial, but more sophisticated systems create the possibility for unpredictability. Misinterpreting human values or intent, algorithmic biases and security risks are all cause for concern, especially with highly developed AI systems where the potential consequences are far greater.

Yu Meng, assistant professor of computer science at ...

New website helps researchers overcome peer reviewers’ preference for animal experiments

2024-09-18

WASHINGTON, D.C.—A new website, AnimalMethodsBias.org, created by the Coalition to Illuminate and Address Animal Methods Bias (COLAAB), provides researchers guidance and resources aimed at helping them successfully publish nonanimal biomedical research by overcoming the preference some peer reviewers have for animal-based research methods.

“We recently found that half of researchers surveyed had been asked by reviewers to add an animal experiment to their otherwise animal-free study,” says Catharine ...

Can the MIND diet lower the risk of memory problems later in life?

2024-09-18

MINNEAPOLIS – People whose diet more closely resembles the MIND diet may have a lower risk of cognitive impairment, according to a study published in the September 18, 2024, online issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology. Results were similar for Black and white participants. These results do not prove that the MIND diet prevents cognitive impairment, they only show an association.

The MIND diet is a combination of the Mediterranean and DASH diets. It includes green leafy vegetables like spinach, ...

Some diabetes drugs tied to lower risk of dementia, Parkinson’s disease

2024-09-18

MINNEAPOLIS – A class of drugs for diabetes may be associated with a lower risk of dementia and Parkinson’s disease, according to a study published in the September 18, 2024, online issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology.

The study looked at sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, which are also known as gliflozins. They lower blood sugar by causing the kidneys to remove sugar from the body through urine.

“We know that these neurodegenerative diseases like dementia and Parkinson’s disease are common and the number of cases is growing as the ...

Propagated corals reveal increased resistance to bleaching across the Caribbean during the fatal heatwave of 2023

2024-09-18

SECORE International’s Coral Seeding approach utilizes assisted reproduction, the breeding of corals, for reef restoration. This approach is realized within a training and partner network throughout the Caribbean. Now, a peer-reviewed study shows that all the effort was worthwhile: during the devastating heatwave in the Caribbean in 2023, the young, bred corals out on the reef stayed healthy while most of the remaining wild corals bleached and many died in the aftermath.

The summer of 2023 was deadly for many corals in the Caribbean Basin. An unprecedented heatwave, in intensity as well as in duration, hit the Caribbean with catastrophic ...

South African rock art possibly inspired by long-extinct species

2024-09-18

A mysterious tusked animal depicted in South African rock art might portray an ancient species preserved as fossils in the same region, according to a study published September 18, 2024 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Julien Benoit of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

The Horned Serpent panel is a section of rock wall featuring artwork of animals and other cultural elements associated with the San people of South Africa, originally painted between 1821 and 1835. Among the painted figures is ...