(Press-News.org) Imagine being one cartwheel away from changing your appearance. One flip, and your brunette locks are platinum blond. That’s not too far from what happens in some prokaryotes, or single-cell organisms, such as bacteria, that undergo something called inversions.

A study led by scientists at Stanford Medicine has shown that inversions, which cause a physical flip of a segment of DNA and change an organism’s genetic identity, can occur within a single gene, challenging a central dogma of biology — that one gene can code for only one protein.

“Bacteria are even cooler than I originally thought, and I’m a microbiologist, so I already thought they were pretty cool,” said Rachael Chanin, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar in hematology. Microbiologists have known for decades that bacteria can flip small sections of their DNA to activate or deactivate genes, Chanin said. To the team’s knowledge, however, those somersaulting pieces have never been found within the confines of a single gene.

In the same way that reversing the order of the letters in the word “dog” could entirely change the meaning of a sentence (“I’m a dog.” versus “I’m a god.”), the within-gene inversion essentially recodes the bacterium’s genetics using the same material. That could result in the activation of a gene, a halt in gene activity or a sequence that codes for the creation of a different protein when inverted.

“I remember seeing the data, and I thought, ‘No way, this can’t be right, because it’s too crazy to be true,’” said Ami Bhatt, PhD, professor of genetics and of medicine. “We then spent the next several years trying to convince ourselves that we had made a mistake. But as far as we can tell, we have not.”

A study detailing the scientists’ findings was published Sept. 25 in Nature. Chanin and former postdoctoral scholar Patrick West, PhD, co-led the study. Bhatt is the senior author.

Flip-flopping

In the 1920s, scientists encountered the first hint of inversions when they were searching for a salmonella treatment. They tried collecting antibodies from animals infected by the bacteria in the hopes that the immune molecules could be transferred to other animals and stave off infection. But it never worked — even the bacterial strains they knew to be genetically identical were able to fight back. Scientists now know that evasion was thanks to an inversion recoding the bacterium in a way that allowed it to escape the animals’ immunity.

Microbiologists have since found inversions occurring in small DNA segments of various kinds of prokaryotes. But Bhatt and her team wondered if they could also happen within a single gene. West created an algorithm, called PhaVa, that identified possible inversions within bacterial genomes.

The software essentially downloads thousands of genome sequence segments from various prokaryotes and scans for regions that look “flippable” — segments with something called inverted repeats, which have a redundant palindromic quality (for instance, ATTCC and CCTTA) — on other side of the potential inversion. The algorithm creates a catalog of what these sequences would look like if they flipped, and it makes comparisons between the made-up genomes and the true sequence. Then it counts the regions where both the flipped and unflipped sequences are present within an organism’s genome, with every match indicating a likely inversion.

The software identified thousands of inversions that exist in bacterial and other prokaryotic species, revealing for the first time that inversions occur within genes. That sparked the idea that not only do single-gene inversions occur, but that they may be relatively common, Bhatt said.

“This was really surprising to us,” Bhatt said. “To our knowledge this has never been seen before.”

One big question remains: What causes an inversion? The team suspects there are specific enzymes that mediate the flip, as well as certain environmental cues that drive the change.

“That’s a to-do now,” Bhatt said. “One of our next steps is to try to decode the molecular grammar so we can build a database of enzymes and a database of the inverted repeats that they flip.”

Interpreting inversions

While there’s still much more to understand about inversions, Bhatt sees potential for numerous applications. “This is effectively a heritable, reversible type of genetic regulation,” she said.

She posits that scientists may eventually be able to use inversions to create a toggleable bacterial system to control their gene expression, something that could behoove synthetic biology research. Or perhaps there are links between certain diseases and the state of bacterial inversions, in which case there may be a way to switch the bacteria’s state and regulate a disease.

“This type of adaptation has just been hiding in front of us, waiting for the right tool and the right technology and biological question to be asked,” Chanin said. “And it makes me wonder, how many more bacterial secrets are just waiting for us to uncover them?”

Researchers from Princeton University contributed to this study.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grants R01 AI148623, R01 AI143757, R01 AI174515, HG000044, HL120824, TL1TR003019, 1S10OD02014101), the AP Giannini Foundation, the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, the Stanford DARE fellowship and the Stand Up 2 Cancer Foundation.

# # #

About Stanford Medicine

Stanford Medicine is an integrated academic health system comprising the Stanford School of Medicine and adult and pediatric health care delivery systems. Together, they harness the full potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education and clinical care for patients. For more information, please visit med.stanford.edu.

END

Gladstone Institutes has established a new scientific award, the Sobrato Prize in Neuroscience, to advance breakthroughs in brain research with high potential for patient impact—and announced it will present the inaugural prize to Yadong Huang, MD, PhD, a trailblazer in Alzheimer’s research.

In his nearly three decades at Gladstone, Huang has led a series of pioneering studies on the genetic underpinnings of Alzheimer’s disease, with discoveries that have opened multiple new avenues for drug development. He ...

Rechargeable lithium-ion batteries are growing in adoption, used in devices like smartphones and laptops, electric vehicles, and energy storage systems. But supplies of nickel and cobalt commonly used in the cathodes of these batteries are limited. New research led by the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) opens up a potential low-cost, safe alternative in manganese, the fifth most abundant metal in the Earth’s crust.

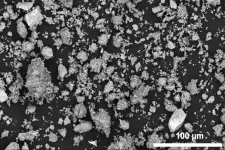

Researchers showed that manganese can be effectively used in emerging cathode materials called disordered rock salts, or DRX. Previous research suggested that to perform well, DRX materials had to be ground down to nanosized ...

Link to Google Drive folder containing images:

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1ZTBXkIFqwl_OyIMrUA1se_iv7hqEm_52?usp=sharing

Link to release:

https://www.washington.edu/news/2024/09/25/tesla-coil-shark-intestines/

FROM: James Urton

University of Washington

206-543-2580

jurton@uw.edu

(Note: researcher contact information at the end)

For immediate release

Sept. 25, 2024

To make fluid flow in one direction down a pipe, it helps to be a shark

Flaps perform essential jobs. From pumping hearts to revving engines, flaps help fluid flow in one direction. ...

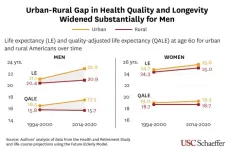

Rural men are dying earlier than their urban counterparts, and they’re spending fewer of their later years in good health, according to new research from the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics.

Higher rates of smoking, obesity and cardiovascular conditions among rural men are helping fuel a rural-urban divide in illness, and this gap has grown over time, according to the study published this week in the Journal of Rural Health. The findings suggest that by the time rural men reach age 60, there are limited opportunities to fully address this disparity, and earlier interventions may be needed to prevent it from widening ...

Held annually, NY Climate Week is a pivotal event in the global climate change calendar. Bringing together notable leaders, celebrities, climate professionals, and innovators from around the world, the event serves as a critical platform for discussing and advancing climate action. This year’s theme, "It’s Time," underscores the urgency for immediate and ambitious efforts to tackle climate change, and the process could be accelerated with Generative AI and other cutting-edge technologies.

Insilico Medicine ...

Young adults who vape show chemical changes in their DNA similar to those found in young adults who smoke — changes known to be linked to the development of cancer — according to a new study just published in the American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology.

A team of researchers from the Keck School of Medicine of USC measured DNA methylation, a chemical modification of DNA that can effectively turn genes “on” or “off, in the oral cells of young adult vapers, smokers and non-users. DNA methylation is vital to normal cellular ...

DALLAS, Sept. 25, 2024 — The American Heart Association, celebrating 100 years of lifesaving service as the world’s leading nonprofit organization focused on heart and brain health for all, is joining with other top cardiovascular research funders around the world to support an international scientific research grant focused on women’s cardiovascular health. Scientific researchers around the world are invited to apply for the award to foster global advancements in understanding and improving the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) among women.

A 2022 presidential advisory ...

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), recently reclassified as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), has become the most prevalent chronic liver disease globally. This reclassification underscores the metabolic dysfunction central to the disease, which spans a spectrum from simple steatosis to more severe forms like steatohepatitis, fibrosis, and cirrhosis. Given the significant overlap between MASLD and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), the therapeutic strategies for MASLD have increasingly focused on addressing metabolic derangements. Despite its global prevalence, no specific drugs have been approved for MASLD, highlighting an urgent need ...

September 25, 2024 (Washington, DC)—The Kissick Family Foundation Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) Grant Program, in partnership with the Milken Institute Science Philanthropy Accelerator for Research and Collaboration (SPARC), today announced six research teams awarded two-year grants to advance scientific understanding of FTD, totaling $3 million in new funding for this disease.

This inaugural cycle of the Kissick Family Foundation FTD Grant Program represents a unique philanthropic strategy that specifically targets basic or early-stage translational research projects that focus on those disease cases ...

Metastatic cancer can be a devastating diagnosis. The cancer is spreading. It may travel to multiple organs in the body. This could mean more pain and ultimately, death.

Unfortunately, just how cancer spreads remains unclear. But now, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Professor Adam Siepel and colleagues have a way to better understand that process. New technology developed at Weill Cornell Medicine barcodes cells to track the highways by which prostate cancer spreads throughout the body.

The resulting roadmap shows that most cancer cells actually stay put within the tumor. However, ...