Mars wasn’t always the cold desert we see today. There’s increasing evidence that water once flowed on the Red Planet’s surface, billions of years ago. And if there was water, there must also have been a thick atmosphere to keep that water from freezing. But sometime around 3.5 billion years ago, the water dried up, and the air, once heavy with carbon dioxide, dramatically thinned, leaving only the wisp of an atmosphere that clings to the planet today.

Where exactly did Mars’ atmosphere go? This question has been a central mystery of Mars’ 4.6-billion-year history.

For two MIT geologists, the answer may lie in the planet’s clay. In a paper appearing in Science Advances, they propose that much of Mars’ missing atmosphere could be locked up in the planet’s clay-covered crust.

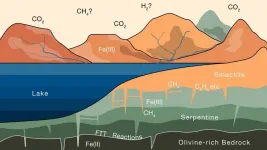

The team makes the case that, while water was present on Mars, the liquid could have trickled through certain rock types and set off a slow chain of reactions that progressively drew carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and converted it into methane — a form of carbon that could be stored for eons in the planet’s clay surface.

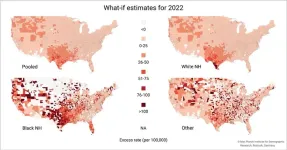

Similar processes occur in some regions on Earth. The researchers used their knowledge of interactions between rocks and gases on Earth and applied that to how similar processes could play out on Mars. They found that, given how much clay is estimated to cover Mars’ surface, the planet’s clay could hold up to 1.7 bar of carbon dioxide, which would be equivalent to around 80 percent of the planet’s initial, early atmosphere.

It’s possible that this sequestered Martian carbon could one day be recovered and converted into propellant to fuel future missions between Mars and Earth, the researchers propose.

“Based on our findings on Earth, we show that similar processes likely operated on Mars, and that copious amounts of atmospheric CO2 could have transformed to methane and been sequestered in clays,” says study author Oliver Jagoutz, professor of geology in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS). “This methane could still be present and maybe even used as an energy source on Mars in the future.”

The study’s lead author is recent EAPS graduate Joshua Murray PhD ’24.

In the folds

Jagoutz’ group at MIT seeks to identify the geologic processes and interactions that drive the evolution of Earth’s lithosphere — the hard and brittle outer layer that includes the crust and upper mantle, where tectonic plates lie.

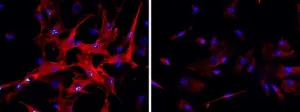

In 2023, he and Murray focused on a type of surface clay mineral called smectite, which is known to be a highly effective trap for carbon. Within a single grain of smectite are a multitude of folds, within which carbon can sit undisturbed for billions of years. They showed that smectite on Earth was likely a product of tectonic activity, and that, once exposed at the surface, the clay minerals acted to draw down and store enough carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to cool the planet over millions of years.

Soon after the team reported their results, Jagoutz happened to look at a map of the surface of Mars and realized that much of that planet’s surface was covered in the same smectite clays. Could the clays have had a similar carbon-trapping effect on Mars, and if so, how much carbon could the clays hold?

“We know this process happens, and it is well-documented on Earth. And these rocks and clays exist on Mars,” Jagoutz says. “So, we wanted to try and connect the dots.”

“Every nook and cranny”

Unlike on Earth, where smectite is a consequence of continental plates shifting and uplifting to bring rocks from the mantle to the surface, there is no such tectonic activity on Mars. The team looked for ways in which the clays could have formed on Mars, based on what scientists know of the planet’s history and composition.

For instance, some remote measurements of Mars’ surface suggest that at least part of the planet’s crust contains ultramafic igneous rocks, similar to those that produce smectites through weathering on Earth. Other observations reveal geologic patterns similar to terrestrial rivers and tributaries, where water could have flowed and reacted with the underlying rock.

Jagoutz and Murray wondered whether water could have reacted with Mars’ deep ultramafic rocks in a way that would produce the clays that cover the surface today. They developed a simple model of rock chemistry, based on what is known of how igneous rocks interact with their environment on Earth.

They applied this model to Mars, where scientists believe the crust is mostly made up of igneous rock that is rich in the mineral olivine. The team used the model to estimate the changes that olivine-rich rock might undergo, assuming that water existed on the surface for at least a billion years, and the atmosphere was thick with carbon dioxide.

“At this time in Mars’ history, we think CO2 is everywhere, in every nook and cranny, and water percolating through the rocks is full of CO2 too,” Murray says.

Over about a billion years, water trickling through the crust would have slowly reacted with olivine — a mineral that is rich in a reduced form of iron. Oxygen molecules in water would have bound to the iron, releasing hydrogen as a result and forming the red oxidized iron which gives the planet its iconic color. This free hydrogen would then have combined with carbon dioxide in the water, to form methane. As this reaction progressed over time, olivine would have slowly transformed into another type of iron-rich rock known as serpentine, which then continued to react with water to form smectite.

“These smectite clays have so much capacity to store carbon,” Murray says. “So then we used existing knowledge of how these minerals are stored in clays on Earth, and extrapolate to say, if the Martian surface has this much clay in it, how much methane can you store in those clays?”

He and Jagoutz found that if Mars is covered in a layer of smectite that is 1,100 meters deep, this amount of clay could store a huge amount of methane, equivalent to most of the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere that is thought to have disappeared since the planet dried up.

“We find that estimates of global clay volumes on Mars are consistent with a significant fraction of Mars’ initial CO2being sequestered as organic compounds within the clay-rich crust,” Murray says. “In some ways, Mars’ missing atmosphere could be hiding in plain sight.”

This work was supported, in part, by the National Science Foundation.

###

Written by Jennifer Chu, MIT News

END