(Press-News.org) Since the first sighting of the first-discovered and largest asteroid in our solar system was made in 1801 by Giuseppe Piazzi, astronomers and planetary scientists have pondered the make-up of this asteroid/dwarf planet. Its heavily battered and dimpled surface is covered in impact craters. Scientists have long argued that visible craters on the surface meant that Ceres could not be very icy.

Researchers at Purdue University and the NASA's Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL) now believe Ceres is a very icy object that possibly was once a muddy ocean world. This discovery that Ceres has a dirty ice crust is led by Ian Pamerleau, PhD student, and Mike Sori, assistant professor in Purdue’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences who published their findings in Nature Astronomy. The duo along with Jennifer Scully, research scientist with JPL, used computer simulations of how craters on Ceres deform over billions of years.

“We think that there's lots of water-ice near Ceres surface, and that it gets gradually less icy as you go deeper and deeper,” Sori said. “People used to think that if Ceres was very icy, the craters would deform quickly over time, like glaciers flowing on Earth, or like gooey flowing honey. However, we've shown through our simulations that ice can be much stronger in conditions on Ceres than previously predicted if you mix in just a little bit of solid rock.”

The team’s discovery is contradictory to the previous belief that Ceres was relatively dry. The common assumption was that Ceres was less than 30% ice, but Sori’s team now believes the surface is more like 90% ice.

“Our interpretation of all this is that Ceres used to be an ‘ocean world’ like Europa (one of Jupiter's moons), but with a dirty, muddy ocean,’” Sori said. “As that muddy ocean froze over time, it created an icy crust with a little bit of rocky material trapped in it.”

Pamerleau explained how they used computer simulations to model how relaxation occurs for craters on Ceres over billions of years.

“Even solids will flow over long timescales, and ice flows more readily than rock. Craters have deep bowls which produce high stresses that then relax to a lower stress state, resulting in a shallower bowl via solid state flow," he said. "So the conclusion after NASA’s Dawn mission was that due to the lack of relaxed, shallow craters, the crust could not be that icy. Our computer simulations account for a new way that ice can flow with only a little bit of non-ice impurities mixed in, which would allow for a very ice-rich crust to barely flow even over billions of years. Therefore, we could get an ice-rich Ceres that still matches the observed lack of crater relaxation. We tested different crustal structures in these simulations and found that a gradational crust with a high ice content near the surface that grades down to lower ice with depth was the best way to limit relaxation of Cerean craters.”

Sori is a planetary scientist whose focus is planetary geophysics. His team addresses questions about the planetary interiors, the connections between planetary interiors and surfaces, and those questions might be resolved with spacecraft missions. His work spans many solid bodies in the solar system, from the Moon and Mars to icy objects in the outer solar system.

“Ceres is the largest object in the asteroid belt, and a dwarf planet. I think sometimes people think of small, lumpy things as asteroids (and most of them are!), but Ceres really looks more like a planet,” Sori said. “It is a big sphere, diameter 950 kilometers or so, and has surface features like craters, volcanoes, and landslides.”

On Sept. 27, 2007, NASA launched the Dawn mission. This mission was the first and only spacecraft to orbit two extraterrestrial destinations — the protoplanet Vesta and Ceres. Although it was launched in 2007, Dawn didn’t reach Ceres until 2015. It orbited the dwarf planet until 2018.

“We used multiple observations made with Dawn data as motivation for finding an ice-rich crust that resisted crater relaxation on Ceres. Different surface features (e.g., pits, domes and landslides, etc.) suggest the near subsurface of Ceres contains a lot of ice,” Pamerleau said. “Spectrographic data also shows that there should be ice beneath the regolith on the dwarf planet and gravity data yields a density value very near that of ice, specifically impure ice. We also took a topographic profile of an actual complex crater on Ceres and used it to construct the geometry for some of our simulations.”

Sori says that because Ceres is the largest asteroid there was suspicion that it could have been any icy object based on some estimates of its mass made from the Earth. those factors made it a great choice for a spacecraft visit.

“To me the exciting part of all this, if we're right, is that we have a frozen ocean world pretty close to Earth. Ceres may be a valuable point of comparison for the ocean-hosting icy moons of the outer solar system, like Jupiter's moon Europa and Saturn's moon Enceladus,” Sori said. “Ceres, we think, is therefore the most accessible icy world in the universe. That makes it a great target for future spacecraft missions. Some of the bright features we see at Ceres' surface are the remnants of Ceres' muddy ocean, now mostly or entirely frozen, erupted onto the surface. So we have a place to collect samples from the ocean of an ancient ocean world that is not too difficult to send a spacecraft to.”

This research was supported by a NASA grant (80NSSC22K1062) in the Discovery Data Analysis Program.

About the Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences at Purdue University

The Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences (EAPS) combines four of Purdue’s most interdisciplinary programs: Geology and Geophysics, Environmental Sciences, Atmospheric Sciences, and Planetary Sciences. EAPS conducts world-class research; educates undergraduate and graduate students; and provides our college, university, state and country with the information necessary to understand the world and universe around us. Our research is globally recognized; our students are highly valued by graduate schools and employers; and our alumni continue to make significant contributions in academia, industry, and federal and state government.

About Purdue University

Purdue University is a public research institution demonstrating excellence at scale. Ranked among top 10 public universities and with two colleges in the top four in the United States, Purdue discovers and disseminates knowledge with a quality and at a scale second to none. More than 105,000 students study at Purdue across modalities and locations, including nearly 50,000 in person on the West Lafayette campus. Committed to affordability and accessibility, Purdue’s main campus has frozen tuition 13 years in a row. See how Purdue never stops in the persistent pursuit of the next giant leap — including its first comprehensive urban campus in Indianapolis, the Mitch Daniels School of Business, Purdue Computes and the One Health initiative — at https://www.purdue.edu/president/strategic-initiatives.

Contributors:

Ian Pamerleau, PhD student with Purdue University’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences

Mike Sori, assistant professor with the Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences at Purdue University

Written by Cheryl Pierce, lead marketing and public relations specialist for the Purdue University College of Science

END

Asteroid Ceres is a former ocean world that slowly formed into a giant, murky icy orb

The asteroid is believed to have a dirty, icy crust according to researchers at Purdue University and NASA

2024-09-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

McMaster researchers discover what hinders DNA repair in patients with Huntington’s Disease

2024-09-27

Researchers with McMaster University have discovered that the protein mutated in patients with Huntington’s Disease doesn't repair DNA as intended, impacting the ability of brain cells to heal themselves.

The research, published in PNAS on Sept. 27, 2024, found that the huntingtin protein helps create special molecules that are important for fixing DNA damage. These molecules, known as Poly [ADP-ribose] (PAR), gather around damaged DNA and, like a net, pull in all the factors needed for the repair process.

In people with Huntington’s Disease, however, the research found that the mutated version of this protein doesn’t function properly ...

Estrogens play a hidden role in cancers, inhibiting a key immune cell

2024-09-27

DURHAM, N.C. – Estrogens are known to drive tumor growth in breast cancer cells that carry its receptors, but a new study by Duke Cancer Institute researchers unexpectedly finds that estrogens play a role in fueling the growth of breast cancers without the receptors, as well as numerous other cancers.

Appearing Sept. 27 in the journal Science Advances, the researchers describe how estrogens not only decrease the ability of the immune system to attack tumors, but also reduce the effectiveness of immunotherapies that are used to treat many cancers, notably triple-negative breast cancers. Triple-negative ...

A new birthplace for asteroid Ryugu

2024-09-27

In December 2020 the space probe Hayabusa 2 brought samples of asteroid Ryugu back to Earth. Since then, the few grams of material have been through quite a lot. After initial examinations in Japan, some of the tiny, jet-black grains traveled to research facilities around the world. There they were measured, weighed, chemically analyzed and exposed to infrared, X-ray and synchroton radiation, among other things. At the MPS, researchers examine the ratios of certain metal isotopes in the samples, as in the current study. Scientists refer to isotopes as variants of the same element that differ only in the number of neutrons in the nucleus. Investigations ...

How are pronouns processed in the memory-region of our brain?

2024-09-27

A new study shows how individual brain cells in the hippocampus respond to pronouns. “This may help us unravel how we remember what we read.”

Read the following sentence: “Donald Trump and Kamala Harris walked into the bar, she sat down at a table.” We all immediately know that it was Kamala who sat at the table, not Donald. Pronouns like “she” help us to understand language, but pronouns can have multiple meanings. Depending on the context, we understand who the pronoun is referring to. But ...

Researchers synthesize high-energy-density cubic gauche nitrogen at atmospheric pressure

2024-09-27

Recently, a research group led by Prof. WANG Xianlong from the Hefei Institutes of Physical Science of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, successfully synthesized high-energy-density materials cubic gauche nitrogen (cg-N) at atmospheric pressure by treating potassium azide (KN3) using the plasma-enhanced chemical vapour deposition technique (PECVD).

The research results were published in Science Advances.

Cg-N is a pure nitrogen material consisting of nitrogen atoms bonded by N-N single bonds, resembling the structure of diamond. It has attracted attention because it has a high-energy-density and produces only nitrogen gas when it decomposes. ...

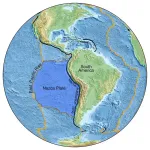

Ancient sunken seafloor reveals earth’s deep secrets

2024-09-27

University of Maryland scientists uncovered evidence of an ancient seafloor that sank deep into Earth during the age of dinosaurs, challenging existing theories about Earth’s interior structure. Located in the East Pacific Rise (a tectonic plate boundary on the floor of the southeastern Pacific Ocean), this previously unstudied patch of seafloor sheds new light on the inner workings of our planet and how its surface has changed over millions of years. The team’s findings were published in the journal Science Advances on September 27, 2024.

Led by geology postdoctoral researcher Jingchuan Wang, the team used innovative seismic imaging techniques to ...

Automatic speech recognition learned to understand people with Parkinson’s disease — by listening to them

2024-09-27

As Mark Hasegawa-Johnson combed through data from his latest project, he was pleasantly surprised to uncover a recipe for Eggs Florentine. Sifting through hundreds of hours of recorded speech will unearth a treasure or two, he said.

Hasegawa-Johnson leads the Speech Accessibility Project, an initiative at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign to make voice recognition devices more useful for people with speech disabilities.

In the project’s first published study, researchers asked an automatic ...

Addressing global water security challenges: New study reveals investment opportunities and readiness levels

2024-09-27

NEW YORK, September 27, 2024 – Water scarcity, pollution, and the burden of waterborne diseases are urgent issues threatening global health and security. A recently published study in the journal Global Environmental Change highlights the pressing need for innovative economic strategies to bolster water security investments, focusing on the “enabling environment” that influences regional readiness for new business solutions.

Initiated and led by researchers at the Advanced Science Research Center at the CUNY Graduate Center (CUNY ASRC), ...

Commonly used drug could transform treatment of rare muscle disorder

2024-09-27

The study, published in Lancet Neurology, detailed the “head-to-head” trial implemented by the researchers to test two drugs, mexiletine and lamotrigine, on people with the condition.

The trial, which was conducted at the UCL Queen Square Multidisciplinary Centre for Neuromuscular Diseases and the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, UCLH, involved 60 adults with confirmed non-dystrophic myotonia.

Patients were randomly assigned to receive either mexiletine for eight weeks followed by lamotrigine for eight weeks, or the reverse order, with a seven-day ...

Michael Frumovitz, M.D., posthumously honored with Julie and Ben Rogers Award for Excellence

2024-09-27

HOUSTON ― The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center has posthumously awarded Michael Frumovitz, M.D., with the Julie and Ben Rogers Award for Excellence in Patient Care. The annual award recognizes employees who consistently demonstrate excellence in their work and dedication to MD Anderson’s mission to end cancer. The award’s focus rotates among the areas of patient care, research, education, prevention and administration, with this year’s award focusing on patient care.

Frumovitz dedicated more than 20 years of service to MD Anderson, most recently as chief patient experience officer and professor in Gynecologic ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

New knowledge on heritability paves the way for better treatment of people with chronic inflammatory bowel disease

Under the Lens: Microbiologists Nicola Holden and Gil Domingue weigh in on the raw milk debate

Science reveals why you can’t resist a snack – even when you’re full

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

[Press-News.org] Asteroid Ceres is a former ocean world that slowly formed into a giant, murky icy orbThe asteroid is believed to have a dirty, icy crust according to researchers at Purdue University and NASA