(Press-News.org)

Key Takeaways:

Microgravity Innovation: The unique conditions of low Earth orbit help to self-assemble human liver tissues with enhanced functionality, compared to Earth-based methods.

Advanced Tissue Preservation: The project includes developing a bioreactor for the stable supercooling preservation of tissues, a critical step toward transporting viable tissues back to Earth.

Clinical Implications: This research could lead to novel stem cell-derived liver tissues, providing an alternative to traditional liver transplants.

An “out-of-this-world” project has the potential to transform the future of tissue engineering and liver transplantation through innovative research conducted aboard the International Space Station (ISS).

Led by Tammy T. Chang, MD, PhD, FACS, a professor of surgery at the University of California, San Francisco, the Chang Laboratory for Liver Tissue Engineering is pioneering the self-assembly of human liver tissues in low Earth orbit (LEO) — the area of space below an altitude of 1,200 miles. This process could significantly enhance the development of complex tissues for medical use on Earth. Strategies to transport these tissues back to Earth and relevant experimental results will be presented at the American College of Surgeons (ACS) Clinical Congress 2024 in San Francisco, California.

This method leverages the unique environment of microgravity to address the limitations of current tissue engineering techniques on Earth. For example, the use of artificial matrices that provide a framework on which cells grow can introduce outside materials and alter cellular function.

“Our findings indicate that microgravity conditions enable the development of liver tissues with better differentiation and functionality than those cultured on Earth,” said Dr. Chang. “This represents a critical step toward creating viable liver tissue implants that could serve as an alternative or adjunct to traditional liver transplants.”

Innovative Approach to Tissue Engineering

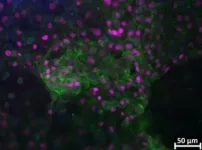

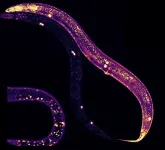

The Chang Laboratory's research focuses on the self-assembly of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) in microgravity. These initial cells are created from normal human cells reprogrammed to act like embryonic stem cells. This means iPSCs can change into many different types of cells. These stem cells are built into liver tissues in microgravity that function like a smaller, simpler liver. Unlike Earth-bound tissue engineering methods that rely on exogenous matrices or culture plates, microgravity allows cells to float freely and organize naturally, resulting in more physiologically accurate tissues.

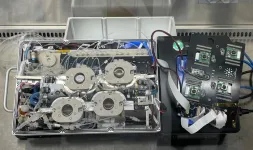

A central component of this project is the development of a custom bioreactor, dubbed the "Tissue Orb," designed to facilitate tissue self-assembly in the weightless environment of space. The bioreactor features an artificial blood vessel and automated media exchange, simulating human tissues’ natural blood flow process.

Future Implications and Cryopreservation Advances

The research team is also working on advanced cryopreservation techniques to transport engineered tissues from space to Earth safely. The project’s next phase involves testing isochoric supercooling, a preservation method that maintains tissues below freezing without damaging them. This technology could extend the shelf life of engineered tissues and potentially be applied to whole organs.

“Our goal is to develop robust preservation techniques that allow us to bring functional tissues back to Earth, where they can be used for a range of biomedical applications, including disease modeling, drug testing, and eventually, therapeutic implantation,” Dr. Chang said.

The Chang Laboratory's spaceflight experiment is scheduled for launch in February 2025. The authors maintain that the research not only showcases the potential of microgravity for advancing tissue engineering but also lays the foundation for future innovations in space-based biomedical manufacturing.

The research is supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) in collaboration with the International Space Station National Laboratory (ISSNL) and the Translational Research Institute through NASA.

Co-authors are Juan C. Reyna, MD; Anthony N. Consiglio, PhD; Alan Maida, BS; Maria Sekyi, PhD; and Boris Rubinsky, PhD.

Authors have no disclosures to report.

Citation: Reyna JC, et al. Liver Tissue Engineering on the International Space Station, Scientific Forum, American College of Surgeons (ACS) Clinical Congress 2024.

# # #

About the American College of Surgeons

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) is a scientific and educational organization of surgeons that was founded in 1913 to raise the standards of surgical practice and improve the quality of care for all surgical patients. The ACS is dedicated to the ethical and competent practice of surgery. Its achievements have significantly influenced the course of scientific surgery in America and have established it as an important advocate for all surgical patients. The ACS has approximately 90,000 members and is the largest organization of surgeons in the world. “FACS” designates that a surgeon is a Fellow of the ACS.

Follow the ACS on social media: X | Instagram | YouTube | LinkedIn | Facebook

END

Key Takeaways

Implementing a system-wide preoperative nutrition program projected an 18% decrease in hospitalization days and a 33% decrease in postoperative complications across multiple surgical specialties.

The program’s financial implications include a projected annual savings of $7.8 million for the payer/insurance sector.

Preoperative nutrition interventions are shown to reduce "outlier days" — hospital days exceeding the expected number — which significantly contributes ...

Key Takeaways

Young adults with colon cancer are typically diagnosed at a later stage and with a more aggressive type of the disease. There are also racial and ethnic disparities, including a significantly higher rate of colon cancer among non-Hispanic Black adults.

Obesity, family history, inflammatory bowel disease, and symptoms, such as abdominal pain or rectal bleeding, are factors strongly associated with colon cancer in younger adults.

Important concerns for ...

Researchers at the University of California San Diego Center for Epigenomics (C4E) have developed a new technique, called Droplet Hi-C, that allows scientists to rapidly determine chromatin organization, the arrangement of genetic material within cells. Chromatin organization influences how genes are activated in our cells and, in turn, how those cells function. In addition to being faster than existing methods for studying chromatin organization, droplet Hi-C is more affordable, which could make it significantly easier for scientists to understand how genes influence the progression of complex diseases, such as cancer and neurological disorders.

The ...

All cancer mutations that cause drug resistance fall into one of four categories. New research has detailed each type, helping to uncover targets for drug development and identify potential effective second-line therapies.

In a new large-scale study, researchers from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, EMBL’s European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI), Open Targets, and collaborators used CRISPR gene editing to map the genetic landscape of drug resistance in cancers, focusing on colon, lung, and Ewing ...

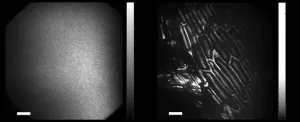

New study introduces a novel computational holography-based method that enables high-resolution, non-invasive imaging through highly scattering media, without the need for traditional tools like guide stars or spatial light modulators. By leveraging computational optimization, the method drastically reduces the number of measurements required and corrects over 190,000 scattered modes using just 25 holographic frames. This innovation shifts the imaging burden from physical hardware to flexible, scalable digital processing, allowing for faster, more efficient imaging across a wide range of fields, from medical diagnostics to autonomous navigation. Its importance lies in providing a versatile, ...

An international study involving people from 11 countries has shown most people, including those in areas most affected by climate change, don’t understand the term ‘Climate Justice’. However they do recognise the social, historical, and economic injustices that characterise the climate crisis. The findings could help shape more effective communications and advocacy.

Researchers from the Univeristy of Nottingham’s School of Psychology led a study that surveyed 5,627 adults in 11 countries (Australia, Brazil, Germany, India, Japan, Netherlands, Nigeria, Philippines, United Arab Emirates, United ...

The migration of the monarch butterfly is one of the wonders of the natural world. Each autumn, a new generation of monarch butterflies is born in the northern United States and southern Canada. Hundreds of millions of these butterflies then fly to the mountains of Central Mexico, between 4,000km and 4,800km away. There, they overwinter in forests of the sacred fir Abies religiosa at high altitudes. Without these sacred firs, the monarchs couldn’t survive their grueling migration.

But under global warming, these forests are predicted to slowly ...

Rapid synthesis of high-entropy alloy nanoparticles (HEA NPs) offers a new opportunity to develop functional materials in various applications. Although some methods have successfully produced HEA NPs, these methods generally require rigorous conditions such as high pressure, high temperature, restricted atmosphere and limited substrates, which impede practical viability.

In a new paper published in Light: Science & Applications, a team of scientists, led by Professor Zhu Liu from the Research Centre for Laser Extreme Manufacturing, Ningbo Institute of Materials Technology and Engineering, Chinese Academy of Sciences, have developed ...

Fuel cells and metal-air batteries are considered the future of clean energy technology, but they rely on one critical reaction—the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR)—to convert energy efficiently. Traditionally, platinum (Pt) and its alloys have been the go-to catalysts for this process due to their high activity, but they come with significant drawbacks, such as high cost and poor stability. Now, a team of researchers led by Yuan Zhao from Jinling Institute of Technology (China) may have found a promising solution. Their ...

Hamilton, ON, Oct. 17, 2024 – McMaster University researchers have discovered a previously unknown cell-protecting function of a protein, which could open new avenues for treating age-related diseases and lead to healthier aging overall.

The team has found that a class of protective proteins known as MANF plays a role in the process that keep cells efficient and working well.

The findings appear in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Our ...