(Press-News.org) A new study has found that after watching a docudrama about the efforts to free a wrongly convicted prisoner on death row, people were more empathetic toward formerly incarcerated people and supportive of criminal justice reform.

The research, led by a team of Stanford psychologists, published Oct. 21 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

“One of the hardest things for groups of people who face stigma, including previously incarcerated people, is that other Americans don’t perceive their experiences very accurately,” said Jamil Zaki, the paper’s senior author and a professor of psychology in the School of Humanities and Sciences (H&S). “One way to combat that lack of empathy for stigmatized groups of people is to get to know them. This is where media comes in, which has been used by psychologists for a long time as an intervention.”

Studying how narrative persuades

The paper incorporates Zaki’s earlier research on empathy with the scholarship of his co-author, Stanford psychologist Jennifer Eberhardt, who has studied the pernicious role of racial bias and prejudice in society for over three decades.

The idea for the study emerged from a conversation Eberhardt had with one of the executive producers of the film Just Mercy, which is based on the book by the lawyer and social justice activist Bryan Stevenson. Stevenson’s book focuses on his efforts at the Equal Justice Initiative to overturn the sentence of Walter McMillian, a Black man from Alabama who in 1987 was sentenced to death for the murder of an 18-year-old white girl, despite overwhelming evidence showing his innocence. The film vividly portrays the systemic racism within the criminal justice system and illustrates how racial bias tragically impacts the lives of marginalized individuals and their families, particularly Black Americans, as they navigate a flawed legal system.

It was around the time of the movie’s release that Eberhardt, who is a professor of psychology in H&S, the William R. Kimball Professor of Organizational Behavior in the Graduate School of Business, and a faculty director of Stanford SPARQ, published her book, Biased: Uncovering the Hidden Prejudice That Shapes What We See, Think, and Do (Viking, 2019), which grapples with many of the same issues as Just Mercy.

On her book tour, she met with many different people, including one of Just Mercy’s executive producers. He approached her with a question originally posed to him by former U.S. President Barack Obama, who had recently watched the film at a private screening. Obama wondered whether watching it could change the way neurons fired in people’s brains.

“I told this producer we don’t have to sit and wonder – this is a question that we can answer through rigorous research,” said Eberhardt. “This paper is a first step in that direction.”

Eberhardt connected with Zaki, and together they designed a study to examine how Just Mercy might change how people think about people who have been pushed to the margins of society.

To measure how watching the film might shape a person’s empathy toward formerly incarcerated people, the researchers asked participants before and after they watched the movie to also watch a set of one- to three-minute-long videos that featured men who had been incarcerated in real life. Participants were asked to rate what they thought these men were feeling as they shared their life stories. These ratings were then measured against what the men actually told the researchers they felt when recounting their experiences.

Opening minds and hearts

The study found that after watching Just Mercy, participants were more empathetic toward those who were formerly incarcerated than those in the control condition.

Their attitudes toward criminal justice reform were also swayed.

The researchers asked participants whether they would sign and share a petition that supported a federal law to restore voting rights to people with a criminal record. They found that people who watched Just Mercy were 7.66% more likely than participants in the control condition to sign a petition.

The study underscores the power of storytelling, Eberhardt said. “Narratives move people in ways that numbers don’t.”

In an early study Eberhardt co-authored, she found that citing statistics on racial disparities is not enough to lead people to take a closer look at systems – in fact, she found that presenting numbers alone can possibly backfire. For example, highlighting racial disparities in the criminal justice system can lead people to be more punitive, not less, and to be more likely to support the punitive policies that help to create those disparities in the first place.

As Eberhardt and Zaki’s study has shown, what does change people’s minds are stories – a finding consistent with a previous study Zaki conducted that found how watching a live theater performance can impact how people perceive social and cultural issues in the U.S.

The psychologists also found that their intervention works regardless of the storyteller’s race, and it had the same effect regardless of people’s political orientation.

“When people experience detailed personal narratives it opens their mind and heart to the people telling those narratives and to the groups from which those people come from,” Zaki said.

END

The transformative power of film

2024-10-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

What happened when a meteorite the size of four Mount Everests hit Earth?

2024-10-21

Billions of years ago, long before anything resembling life as we know it existed, meteorites frequently pummeled the planet. One such space rock crashed down about 3.26 billion years ago, and even today, it’s revealing secrets about Earth’s past.

Nadja Drabon, an early-Earth geologist and assistant professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, is insatiably curious about what our planet was like during ancient eons rife with meteoritic bombardment, when only single-celled bacteria and archaea reigned – and when it all started to change. When ...

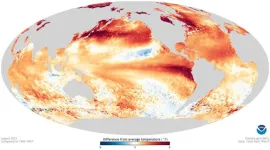

Weather-changing El Niño oscillation is at least 250 million years old

2024-10-21

DURHAM, N.C. – The El Niño event, a huge blob of warm ocean water in the tropical Pacific Ocean that can change rainfall patterns around the globe, isn't just a modern phenomenon.

A new modeling study from a pair of Duke University researchers and their colleagues shows that the oscillation between El Niño and its cold counterpart, La Niña, was present at least 250 million years in the past, and was often of greater magnitude than the oscillations we see today.

These temperature swings were more intense in the past, and the oscillation occurred even when the continents were in different places than they are now, according to the study, which appears the week ...

Evolution in action: How ethnic Tibetan women thrive in thin oxygen at high altitudes

2024-10-21

Breathing thin air at extreme altitudes presents a significant challenge—there’s simply less oxygen with every lungful. Yet, for more than 10,000 years, Tibetan women living on the high Tibetan Plateau have not only survived but thrived in that environment.

A new study led by Cynthia Beall, Distinguished University Professor Emerita at Case Western Reserve University, answers some of those questions. The new research, recently published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), reveals how the Tibetan women’s physiological ...

Microbes drove methane growth between 2020 and 2022, not fossil fuels, study shows

2024-10-21

Microbes in the environment, not fossil fuels, have been driving the recent surge in methane emissions globally, according to a new, detailed analysis published Oct 28 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by CU Boulder researchers and collaborators.

“Understanding where the methane is coming from helps us guide effective mitigation strategies,” said Sylvia Michel, a senior research assistant at the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research(INSTAAR) and a doctoral student in the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences at CU Boulder. “We need to know more about those emissions to ...

Re-engineered, blue light-activated immune cells penetrate and kill solid tumors

2024-10-21

HERSHEY, Pa. — Immunotherapies that mobilize a patient’s own immune system to fight cancer have become a treatment pillar. These therapies, including CAR T-cell therapy, have performed well in cancers like leukemias and lymphomas, but the results have been less promising in solid tumors.

A team led by researchers from the Penn State College of Medicine has re-engineered immune cells so that they can penetrate and kill solid tumors grown in the lab. They created a light-activated switch that controls protein function associated with cell ...

Rapidly increasing industrial activities in the Arctic

2024-10-21

The Arctic is threatened by strong climate change: the average temperature has risen by about 3°C since 1979 – almost four times faster than the global average. The region around the North Pole is home to some of the world’s most fragile ecosystems, and has experienced low anthropogenic disturbance for decades. Warming has increased the accessibility of land in the Arctic, encouraging industrial and urban development. Understanding where and what kind of human activities take place is key to ensuring sustainable development in the region – for both people and the environment. Until now, a comprehensive assessment of this part of the world has ...

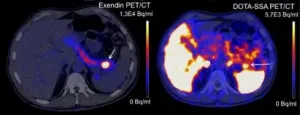

Scan based on lizard saliva detects rare tumor

2024-10-21

A new PET scan reliably detects benign tumors in the pancreas, according to research led by Radboud university medical center. Current scans often fail to detect these insulinomas, even though they cause symptoms due to low blood sugar levels. Once the tumor is found, surgery is possible.

The pancreas contains cells that produce insulin, known as beta cells. Insulin is a hormone that helps the body absorb sugar from the blood and store it in places like muscle cells. This regulates blood sugar levels. In rare cases, the beta cells malfunction, resulting in a benign tumor called ...

Rare fossils of extinct elephant document the earliest known instance of butchery in India

2024-10-21

During the late middle Pleistocene, between 300 and 400 thousand years ago, at least three ancient elephant relatives died near a river in the Kashmir Valley of South Asia. Not long after, they were covered in sediment and preserved along with 87 stone tools made by the ancestors of modern humans.

The remains of these elephants were first discovered in 2000 near the town of Pampore, but the identity of the fossils, cause of death and evidence of human intervention remained unknown until now.

A team ...

Argonne materials scientist Mercouri Kanatzidis wins award from American Chemical Society for Chemistry of Materials

2024-10-21

Mercouri Kanatzidis, a materials scientist at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Argonne National Laboratory and professor at Northwestern University, will receive the 2025 ACS Award in the Chemistry of Materials from the American Chemical Society, the nation’s leading professional organization of chemists.

The award “recognizes and encourages creative work in the chemistry of materials,” according to the citation.

At Argonne, Kanatzidis’s work has focused on the implications of a ...

Lehigh student awarded highly selective DOE grant to conduct research at DIII-D National Fusion Facility

2024-10-21

When it comes to sustainable energy, harnessing nuclear fusion is—for many—a holy grail of sorts. Unlike climate-warming fossil fuels, fusion offers a clean, nearly limitless source of energy by combining light atomic nuclei to form heavier ones, releasing vast amounts of energy in the process.

But it isn’t easy replicating and controlling the process that powers the sun.

“We eventually want to move to producing energy this way,” says Brian Leard ’21 ’25G, a ...