(Press-News.org) Researchers at the Complexity Science Hub and Santa Fe Institute have developed a model to calculate how quickly or slowly an organism should ideally learn in its surroundings. An organism’s ideal learning rate depends on the pace of environmental change and its life cycle, they say.

Every day, we wake to a world that is different, and we adjust to it. Businesses face new challenges and competitors and adapt or go bust. In biology, this is a question of survival: every organism, from bacteria to blue whales, faces the challenge of adapting to environments that are constantly in flux. Animals must learn where to seek nourishing food, even as those food sources change with the seasons. However, learning takes time and energy – an organism that learns too slowly will lag behind environmental changes, while one that learns too quickly will waste effort trying to track meaningless fluctuations.

The new mathematical model provides a quantitative answer to the question: What is the optimal pace of learning for an organism in a changing world? “The key insight is that the ideal learning rate increases in the same way regardless of the pace of environmental change, whether the organism changes its environment or alters its interaction with it. This suggests a generalizable phenomenon that may underlie learning in a variety of ecosystems,” states CSH PostDoc Eddie Lee.

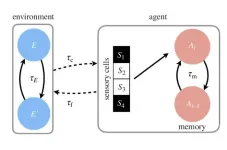

The researchers' model imagines an environment that alternates between different states, such as wet and dry seasons, at a characteristic tempo. The organism senses this environmental state and records a memory of the past states. But older memories decay in importance over time, at a rate that defines the organism's learning timescale.

LEARNING AT THE SQUARE ROOT OF CHANGE

What is the optimal learning timescale to maximize adaptation to the environment? The model predicts a universal law: the learning timescale should scale as the square root of the environmental timescale.

For example, if the environment fluctuates twice as slowly, the organism's learning rate should decrease by a factor of 1.4 (the square root of 2). This square root scaling represents an optimal compromise between learning too quickly and too slowly. Importantly, a square root relation indicates that there are diminishing returns to longer memory.

“The model also simulates organisms that don't just passively learn, but can actively reshape their environment – an ability called niche construction,” says Lee, who is an ESPRIT Fellow of the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) at CSH. If an organism has "stabilizing" powers to make its environment more constant, it gains an evolutionary edge. However, this advantage only accrues if the organism can monopolize the benefits of the stable environment. If freeloading competitors also exploit the stabilized niche, the niche construction strategy falls apart. An example: Beavers actively shape their environment by building dams in rivers, creating stable ponds that provide habitats for themselves and other species. This construction offers them a significant evolutionary advantage, as it ensures a consistent food supply and protection from predators. However, this advantage can diminish if other organisms, like muskrats or fish, exploit the resources of the created habitat.

METABOLIC OVERHEAD FOR LARGE ANIMALS

Finally, the researchers assess how learning ability interacts with the metabolic costs of being alive, meaning the energy demands of the body. They predict that for small, short-lived creatures like insects, the costs of learning and memory are paramount. In contrast, for larger, longer-lived animals like mammals, the costs of learning are dwarfed by metabolic overhead.

This predicts that small, short-lived organisms have well-tuned memory for their environments. “In contrast, larger organisms like elephants have longer memories, but exactly how long they retain information may have more to do with non-learning costs or other types of environments such as social groups which impose further cognitive demands,”, says Lee. Thus, it might not be totally appropriate to deride the well-tuned, “memory of a flea.”

The new model offers a quantitative framework for understanding how organisms balance the competing demands of learning and other survival imperatives in an ever-changing world. The results suggest an optimal pace of adaptation tuned to the speed of environmental change and the lifespan of the organism across the living world–from microbes to humans.

About the study

The study “Constructing stability: optimal learning in noisy ecological niches,” by E.D. Lee, J.C. Flack and D.C. Krakauer was published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences (doi: 10.1098/rspb.2024.1606).

About CSH

The Complexity Science Hub (CSH) is Europe’s research center for the study of complex systems. We derive meaning from data from a range of disciplines — economics, medicine, ecology, and the social sciences — as a basis for actionable solutions for a better world. Established in 2015, we have grown to over 70 researchers, driven by the increasing demand to gain a genuine understanding of the networks that underlie society, from healthcare to supply chains. Through our complexity science approaches linking physics, mathematics, and computational modeling with data and network science, we develop the capacity to address today’s and tomorrow’s challenges.

END

Why elephants never forget but fleas have, well, the attention span of a flea

2024-10-31

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Childhood neglect associated with stroke, COPD, cognitive impairment, and depression

2024-10-31

Toronto, ON, – New research from the University of Toronto found that childhood neglect, even in the absence of childhood sexual abuse and physical abuse, is linked with a wide range of mental and physical health problems in adulthood.

“While a large body of research has established the detrimental impact of childhood physical and sexual abuse on adult health outcomes, much less is known about whether neglect, in the absence of abuse, has similar negative outcomes,” said first author, Linxiao Zhang, a PhD student at the Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work (FIFSW) at the University of Toronto. “Our research underlines the importance of health professionals ...

Landmark 20-year study of climate change impact on permafrost forests

2024-10-31

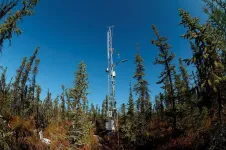

In perhaps the first long-term study of CO2 fluxes in northern forests growing on permafrost, an Osaka Metropolitan University-led research team has found that climate change increased not only the sources of carbon, but also the CO2 sinks.

The 20-year observation from 2003-2022 in the interior of Alaska showed that while CO2 sinks turned into sources during the first decade, the second decade showed a nearly 20% increase in CO2 sinks.

Graduate School of Agriculture Associate Professor Masahito Ueyama and colleagues found that warming led to wetness, which in turn aided the growth of black spruce trees. During photosynthesis, the growing trees were using the increasing ...

Researchers take broadband high-resolution frequency combs into the UV

2024-10-31

WASHINGTON — Researchers have developed a new ultrafast laser platform that generates ultra-broadband ultraviolet (UV) frequency combs with an unprecedented one million comb lines, providing exceptional spectral resolution. The new approach, which also produces extremely accurate and stable frequencies, could enhance high-resolution atomic and molecular spectroscopy.

Optical frequency combs — which emit thousands of regularly spaced spectral lines — have transformed fields like metrology, spectroscopy and precision timekeeping via optical atomic clocks, earning the 2005 Nobel Prize in Physics.

The ...

Not going out is the “new normal” post-Covid, say experts

2024-10-31

Compared with just before the Covid-19 pandemic, people are spending nearly an hour less a day doing activities outside the home, behaviour that researchers say is a lasting consequence of the pandemic.

A new study published in the peer-reviewed Journal of the American Planning Association reveals an overall drop since 2019 of about 51 minutes in the daily time spent on out-of-home activities, plus an almost 12-minute reduction in time spent on daily travel such as driving or taking public transportation.

The analysis, based on a survey of 34,000 Americans, ...

Study shows broader screening methods help prevent spread of dangerous fungal pathogen in hospitals

2024-10-31

Study Shows Broader Screening Methods Help Prevent Spread of Dangerous Fungal Pathogen in Hospitals

Screening high-risk patients for Candida auris allows for early detection and implementation of infection control measures to prevent hospital outbreaks

Arlington, Va. — October 31, 2024 — A new study published today in the American Journal of Infection Control (AJIC) describes the outcome of a shift in hospital screening protocols for Candida auris, a dangerous and often drug-resistant fungal pathogen that spreads easily in hospital environments. A comparison of screening results and patient outcomes before ...

Research spotlight: Testing a model for depression care in Malawi using existing medical infrastructure

2024-10-31

How would you summarize your study for a lay audience?

We tested a model of depression care in Malawi, a low-income country in sub-Saharan Africa, that builds off the infrastructure of the country’s HIV delivery system. The intervention involved clinical officers who delivered medications for depression, and it involved lay personnel, people living in the community, to deliver psychotherapy. Unlike past research, we did not limit our evaluation to improvements in depression; we also looked at improvements in other chronic health conditions that participants had, and we measured effects on household members.

What knowledge gap does your study help to ...

Depression care in low-income nations can improve overall health

2024-10-31

Treating people in low-income countries for major depressive disorder can also help improve their physical health and household members’ wellbeing, demonstrating that mental health treatments can be cost effective, according to a new RAND study.

Researchers examined a program in the sub-Saharan nation of Malawi that builds off the infrastructure of the country’s HIV care system and trains local people in rural communities to help treat people who suffer from depression.

The study found participants had significant improvements in their depression symptoms, ...

The BMJ investigates dispute over US group’s involvement in WHO’s trans health guideline

2024-10-30

The World Health Organization (WHO) says that it is adhering to standard protocol in pursuing its transgender health guideline, but the process has been criticised for lacking transparency and an association with WPATH - an organisation that supports the “gender affirming” approach, including hormones and surgery, for all ages - and is under fire for meddling with its own guideline development.

In The BMJ today, freelance journalist Jennifer Block investigates these concerns and the questions they raise about how evidence based the panel’s recommendations would be.

Earlier ...

Personal info and privacy control may be key to better visits with AI doctors

2024-10-30

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Artificial intelligence (AI) may one day play a larger role in medicine than the online symptom checkers available today. But these “AI doctors” may need to get more personal than human doctors to increase patient satisfaction, according to a study led by researchers at Penn State. They found that the more social information an AI doctor recalls about patients, the higher the patients’ satisfaction, but only if they were offered privacy control.

The research team published their findings in the journal Communication Research.

“We tend to think of AI doctors as machines ...

NIH study demonstrates long-term benefits of weight-loss surgery in young people

2024-10-30

What: Young people with severe obesity who underwent weight-loss surgery at age 19 or younger continued to see sustained weight loss and resolution of common obesity-related comorbidities 10 years later, according to results from a large clinical study funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Study participants with an average age of 17 underwent gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy weight-loss surgery. After 10 years, participants sustained an average of 20% reduction in body mass index (BMI), 55% reduction of type 2 diabetes, 57% reduction of hypertension, and 54% reduction of abnormal cholesterol. Both gastric ...