Scientists at Northwestern and Case Western Reserve universities have developed the first polymer-based therapeutic for Huntington’s disease, an incurable, debilitating illness that causes nerve cells to break down in the brain.

Patients with Huntington’s disease have a genetic mutation that triggers proteins to misfold and clump together in the brain. These clumps interfere with cell function and eventually lead to cell death. As the disease progresses, patients lose the ability to talk, walk, swallow and concentrate. Most patients die within 10 to 20 years after symptoms first appear.

The new treatment leverages peptide-brush polymers, which act as a shield to prevent proteins from binding to one another. In studies in mice, the treatment successfully rescued neurons to reverse symptoms. The treated mice also experienced no significant side effects, confirming the therapy is nontoxic and well tolerated.

Although the treatment needs further testing, the researchers imagine it potentially someday could be administered as a once-weekly injection to delay disease onset or reduce symptoms in patients with the genetic mutation.

The study will be published on Friday (Nov. 1), in the journal Science Advances.

“Huntington’s is a horrific, insidious disease,” said Northwestern’s Nathan Gianneschi, who led the polymer therapeutic development. “If you have this genetic mutation, you will get Huntington’s disease. It’s unavoidable; there’s no way out. There is no real treatment for stopping or reversing the disease, and there is no cure. These patients really need help. So, we started thinking about a new way to address this disease. The misfolded proteins interact and aggregate. We’ve developed a polymer that can fight those interactions.”

Gianneschi is the Jacob and Rosaline Cohn Professor of Chemistry at Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences and professor of materials science and engineering and biomedical engineering at Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering as well as in Pharmacology at Feinberg School of Medicine. He also is a member of the International Institute of Nanotechnology. Gianneschi co-led the study with Xin Qi, the Jeanette M. and Joseph S. Silber Professor of Brain Sciences and co-director of the Center for Mitochondrial Research and Therapeutics, at Case Western Reserve University.

Promising peptide

The new study builds on previous work from Qi’s laboratory at Case Western Reserve. In 2016, Qi and her team identified a protein (valosin-containing protein or VCP) that abnormally binds to the mutant Huntington protein, causing protein aggregates. These aggregates accumulate within a cell’s mitochondria, an organelle that generates the energy needed to power a cell’s biochemical reactions. Without functioning mitochondria, the cells become dysfunctional and then self-destruct.

As part of that study, Qi also uncovered a naturally occurring peptide that disrupts the interaction between the VCP and the mutant Huntington protein. In cells exposed to the peptide, both the VCP and mutant Huntington protein bound to the peptide — instead of each other.

“Qi’s team identified a peptide that comes from the mutant protein itself and basically controls the protein-protein interface,” Gianneschi said. “That peptide inhibited mitochondrial death, so it showed promise.”

Pulling apart proteins like Velcro

But the peptide, by itself, faced several limitations. Because they are easily broken down by enzymes, peptides have a short lifespan in the body and often have difficulty effectively entering cells. For the peptide to inhibit Huntington’s disease, it needs to cross the blood-brain barrier in large enough quantities to prevent large-scale protein aggregation.

“The peptide has a very small footprint with respect to the protein interfaces,” Gianneschi said. “The proteins stick to each other like Velcro. In this analogy, one protein has hooks and the other has loops. The peptide, on its own, is like trying to undo a patch of Velcro by pulling apart one hook and loop at a time. By the time you get to the bottom of the patch, the top has already come back together and resealed. We needed something big enough to disrupt the entire interface.”

To overcome these obstacles, Gianneschi and his team developed a biocompatible polymer that displays multiple copies of the active peptide. The new structure has a polymer backbone with peptides attached like branches. Not only does the structure protect the peptides from destructive enzymes, it also helps them cross the blood-brain barrier and enter cells.

Experimental results

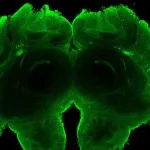

In laboratory experiments, Gianneschi and his team injected the protein-like polymer into a mouse model of Huntington’s disease. The polymers stayed in the body 2,000 times longer than traditional peptides. In biochemical and neuropathological examinations, the researchers found the treatment prevented mitochondrial fragmentation to preserve the health of brain cells. According to Gianneschi, the mice with Huntington’s disease also lived longer and behaved more like normal mice.

“In one study, the mice are examined in an open field test,” Gianneschi said. “In the animals with Huntington’s, as the disease progresses, they stay along the edges of the box. Whereas normal animals cross back and forth to explore the space. The treated animals with Huntington’s disease started to do the same thing. It’s quite compelling when you see animals behave more normally than they would otherwise.”

Next, Gianneschi will continue to optimize the polymer, with plans to explore its use in other neurodegenerative diseases.

“My childhood friend was diagnosed with Huntington’s at age 18 through a genetic test,” Gianneschi said. “He’s now in an assisted living facility because he needs 24-hour, full-time care. I remain highly motivated — both personally and scientifically — to continue traveling down the path.”

The study, “Proteomimetic polymer blocks mitochondrial damage, rescues Huntington’s neurons and slows onset of neuropathy in vivo,” was supported by the International Institute of Nanotechnology Convergence Science Medicine Institute grant, National Institutes of Health (award numbers 1F31AG076334, R01AG065240, R01NS115903, R01AG076051 and RF1AG074346.)

END