(Press-News.org) Why do mice have tails?

The answer to this is not as simple as you might think. New research from the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) has shown that there’s more to the humble mouse tail than previously assumed. Using a novel experimental setup involving a tilting platform, high-speed videography and mathematical modelling, scientists have demonstrated how mice swing their tails like a whip to maintain balance – and these findings can help us better understand balance issues in humans, paving the way for spotting and treating neurodegenerative diseases like multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease at earlier stages.

“Mice are ubiquitous in neuroscience because of their genetic, biological and behavioral similarity to us, and yet the role of their characteristic tail has remained elusive,” explains Dr. Salvatore Lacava from the Neuronal Rhythms in Movement Unit at OIST and first author on the study now published in the Journal of Experimental Biology. “By getting a deeper understanding of how healthy mice balance and by improving the ways in which we assess their performance, we can better explore the neurological mechanisms behind, as well as potential treatments for, conditions that affect motor control and stability.”

Balancing with a flick of the tail

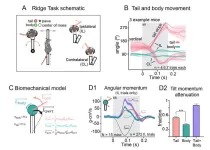

It has long been assumed that mice use their tail as a passive counterweight, like how you might lower your body on a bicycle when riding over difficult terrain or in sharp turns. “We spent a lot of time observing healthy mice,” recounts Dr. Lacava. “But instead of a passive use as a counterweight, we were surprised to find a consistently active use of their tail in maintaining balance.” To regain their balance when the surface underneath them tilts, the researchers found that mice rotate their tail extremely quickly in the opposite direction of the tilt. Even though their tail is light, the sheer speed of the tail swing produces a significant amount of angular momentum, pulling their body away from the fall. “It would be like if you could swing a whip fast enough to pull yourself in the direction of the crack to avoid falling backwards.”

In addition to sudden shifts in balance, they also found that mice use their tail to remain balanced when going across narrow platforms. Here, the tail is continuously flicked in the opposite direction of the movements of the body, mitigating the changes in balance as the mouse moves. During the most challenging trials, the tail is also kept at a lower angle, supplementing the active use with the passive use as a counterweight.

Previously, the role of mice tails in maintaining balance was poorly understood and often overlooked in experiments. “While mice are crucial in neuroscience because of their likeness to us, our study underscores the importance of counting factors that we humans may not have – like a tail – but which impacts the research into conditions that do affect us,” points out Professor Marylka Yoe Uusisaari, leader of the unit and senior author on the paper. In demonstrating the active role of mice tails, this study paves the way for more accurate measurements of balance performance in healthy mice, setting a solid benchmark for research into various conditions that affect balance, such as neurodegenerative diseases.

A challenge to mice and research

In addition to elucidating the role of mice tails, the researchers also developed a new experimental setup for assessing mouse balance. The previous standard is a beam-walking test, where mice are tasked with crossing a 1cm wide ridge under various conditions. If the mouse fell off, they were counted as being off-balance. But for healthy mice, this test is a cakewalk. As Prof. Uusisaari explains, “most mice species are arboreal animals, living in trees. They have adapted to swiftly cross difficult surfaces like thin branches. Our new setup accounts for this by challenging the mice with narrower surfaces and sudden movements.”

The new setup uses a range of platform widths, from 1cm down to 4mm, as well as random 10-to-30-degree rotations in either direction. And instead of evaluating balance as the ability of being able to stay on the ridge, the researchers redefined balance as a metric of how well the mouse’s body is positioned over its feet. To capture these finer nuances of the movements, the researchers created a biomechanical model based on a neural network trained to track the position of different parts of the mouse as it traverses the platform. This model allowed the researchers to calculate the angular momentum of the tail relative to the tilt of the body, showing how it counteracts the tilt.

“We want to be able to spot and treat balancing issues in humans before they become so severe that the patient struggles to walk in a straight line,” summarizes Dr. Lacava. “With this study, we have now set the same standard for the mice.” By demonstrating the role of mice tails in movement, and by raising the experimental bar for healthy mice, researchers are now better equipped to assess subtle changes in balance performance, allowing for much greater precision in studying the early effects of neurodegenerative diseases.

END

Mice tails whip up new insights into balance and neurodegenerative disease research

New study using a novel experimental setup has shown how healthy mice flick their tails to maintain balance

2024-11-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New study: Earthquake prediction techniques lend quick insight into strength, reliability of materials

2024-11-06

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Materials scientists can now use insight from a very common mineral and well-established earthquake and avalanche statistics to quantify how hostile environmental interactions may impact the degradation and failure of materials used for advanced solar panels, geological carbon sequestration and infrastructure such as buildings, roads and bridges.

The new study, led by the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign in collaboration with Sandia National Laboratories and Bucknell University, shows that the amount ...

Vitamin D during pregnancy boosts children’s bone health even at age seven

2024-11-06

Vitamin D during pregnancy boosts children’s bone health even at age seven

Children whose mothers took extra vitamin D during pregnancy continue to have stronger bones at age seven, according to new research led by the University of Southampton and University Hospital Southampton (UHS).

Bone density scans revealed that children born to mothers who were given vitamin D supplements during pregnancy have greater bone mineral density in mid-childhood. Their bones contain more calcium and other minerals, making them stronger and less likely to break.

Researchers say the findings, published in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, reinforce the importance of ...

Use of “genetic scissors” carries risks

2024-11-06

The CRISPR molecular scissors have the potential to revolutionize the treatment of genetic diseases. This is because they can be used to correct specific defective sections of the genome. Unfortunately, however, there is a catch: under certain conditions, the repair can lead to new genetic defects – as in the case of chronic granulomatous disease. This was reported by a team of basic researchers and physicians from the clinical research program ImmuGene at the University of Zurich (UZH).

Chronic granulomatous disease is ...

Does work-related stress compromise cardiovascular health?

2024-11-06

In a large multi-ethnic group of adults in the United States without cardiovascular disease, those with work-related stress were more likely to have unfavorable measures of cardiovascular health. The findings are published in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

For the analysis, investigators assessed data collected between 2000 and 2002 for 3,579 community-based men and women aged 45–84 years enrolled in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Cardiovascular health was determined based on seven metrics—smoking, physical activity, body mass index, diet, total cholesterol, blood pressure, and blood glucose—with each metric contributing zero points, ...

New research may lead to potatoes that are less reliant on nitrogen fertilizers

2024-11-06

Because nitrogen fertilizers contribute to global greenhouse gas emissions, scientists are looking for ways to modify agricultural plants so that they rely on less nitrogen. In research published in New Phytologist, investigators have found that blocking a particular protein may achieve this goal in potatoes.

The protein, called Solanum tuberosum CYCLING DOF FACTOR 1 (StCDF1), binds to DNA and plays a key role in regulating tuberization in potatoes. In this latest research, investigators found that StCDF1 ...

Do commercial ties influence ESG ratings?

2024-11-06

An analysis published in the Journal of Accounting Research uncovers evidence that conflicts of interest arising from commercial ties lead to bias in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) ratings.

Investigators focused on Moody’s and S&P’s acquisitions of ESG rating agencies Vigeo Eiris and RobecoSAM. Their analysis revealed that after these ESG rating agencies were acquired by Moody’s and S&P, they issued higher ratings to existing paying clients of Moody’s and S&P. Specifically, ...

Study assesses "gendered space" in financial institutions in Pakistan

2024-11-06

In Islamic cultures, purdah, which literally means “curtain,” is a practice that involves the seclusion of women from public observation and the enforcement of high standards of female modesty. Research published in the Journal of Management Studies examines the significance of purdah (spatial modesty) in gender relations in financial institutions in Pakistan.

The research was based on the lived experiences of women and men working in two banks based in Pakistan. One of the study’s co-authors, Shafaq Chaudhry, PhD, of the University of Central Lancashire, in the UK, sought internships for six weeks ...

Chinese herbal medicine’s potential in preventing dementia

2024-11-06

Attempts to discover a breakthrough dementia drug might be drawing attention these days, but traditional medicinal products can offer hints for preventive medicine.

A research group led by Specially Appointed Professor Takami Tomiyama of Osaka Metropolitan University’s Graduate School of Medicine has found that administering the dried seeds of a type of jujube called Ziziphus jujuba Miller var. spinosa, used as a medicinal herb in traditional Chinese medicine, holds promise in restoring cognitive and motor function in model mice.

By administering hot water extracts of Zizyphi spinosi semen to model mice with ...

Firms that read more perform better

2024-11-06

[Vienna, November 6, 2024] — “Tell me how you read and I’ll tell you who you are.” By analyzing online reading behavior across millions of firms worldwide, a new study out of the Complexity Science Hub (CSH) connects how much information companies consume and how the consumption relates to their size.

"The way companies consume information is reminiscent of biological organisms. They take in, transmit, and transform information to make decisions. As with organisms, there are important size differences. Larger firms tend to consume information more efficiently ...

Tightly tied waist cord of saree underskirt may pose cancer risk, warn doctors

2024-11-06

A tightly tied waist cord of the underskirt (petticoat) traditionally worn under a saree, particularly in rural parts of India, may lead to what has been dubbed ‘petticoat cancer,’ warn doctors in the journal BMJ Case Reports after treating two women with this type of malignancy.

The continued pressure and friction on the skin can cause chronic inflammation, leading to ulceration, and, in some cases, progression to skin cancer, say the authors.

This phenomenon has previously been described as “saree cancer,” but it is the tightness of the waist cord that’s to blame, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Pregnancy complications impact women’s stress levels and cardiovascular risk long after delivery

Spring fatigue cannot be empirically proven

Do prostate cancer drugs interact with certain anticoagulants to increase bleeding and clotting risks?

Many patients want to talk about their faith. Neurologists often don't know how.

AI disclosure labels may do more harm than good

The ultra-high-energy neutrino may have begun its journey in blazars

Doubling of new prescriptions for ADHD medications among adults since start of COVID-19 pandemic

“Peculiar” ancient ancestor of the crocodile started life on four legs in adolescence before it began walking on two

AI can predict risk of serious heart disease from mammograms

New ultra-low-cost technique could slash the price of soft robotics

Increased connectivity in early Alzheimer’s is lowered by cancer drug in the lab

Study highlights stroke risk linked to recreational drugs, including among young users

Modeling brain aging and resilience over the lifespan reveals new individual factors

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

[Press-News.org] Mice tails whip up new insights into balance and neurodegenerative disease researchNew study using a novel experimental setup has shown how healthy mice flick their tails to maintain balance