(Press-News.org)

A Northwestern University-led team of engineers has developed a new type of wearable device that stimulates skin to deliver various complex sensations.

The thin, flexible device gently adheres to the skin, providing more realistic and immersive sensory experiences. Although the new device obviously lends itself to gaming and virtual reality (VR), the researchers also envision applications in healthcare. For example, the device could help people with visual impairments “feel” their surroundings or give feedback to people with prosthetic limbs.

The study will be published on Wednesday (Nov. 6) in the journal Nature.

The device is the latest advance in wearable technology from Northwestern bioelectronics pioneer John A. Rogers. The new study builds on work published in 2019 in Nature, in which his team introduced “epidermal VR,” a skin-interfaced system that communicates touch through an array of miniature vibrating actuators across large areas of the skin, with fast wireless control.

“Our new miniaturized actuators for the skin are far more capable than the simple ‘buzzers’ that we used as demonstration vehicles in our original 2019 paper,” Rogers said. “Specifically, these tiny devices can deliver controlled forces across a range of frequencies, providing constant force without continuous application of power. An additional version allows the same actuators to provide a gentle twisting motion at the surface of the skin to complement the ability to deliver vertical force, adding realism to the sensations.”

Rogers is the Louis A. Simpson and Kimberly Querrey Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, Biomedical Engineering and Neurological Surgery, with appointments in Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering and Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. He also directs the Querrey Simpson Institute for Bioelectronics.

Rogers co-led the work with Northwestern’s Yonggang Huang, the Jan and Marcia Achenbach Professorship in Mechanical Engineering at McCormick; Hanqing Jiang of Westlake University in China; and Zhaoqian Xie of Dalian University of Technology in China. Jiang’s team built the small modifying structures needed to enable twisting motions.

Leveraging skin-stored energy

The new device comprises a hexagonal array of 19 small magnetic actuators encapsulated within a thin, flexible silicone-mesh material. Each actuator can deliver different sensations, including pressure, vibration and twisting. Using Bluetooth technology in a smartphone, the device receives data about a person’s surroundings for translation into tactile feedback — substituting one sensation (like vision) for another (touch).

Although the device is powered by a small battery, it saves energy using a clever “bistable” design. This means it can stay in two stable positions without needing constant energy input. When the actuators press down, it stores energy in the skin and in the device’s internal structure. When the actuators push back up, the device uses the small amount of energy to release the stored energy. So, the device only uses energy when the actuators change position. With this energy-efficient design, the device can operate for longer periods of time on a single battery charge.

“Instead of fighting against the skin, the idea was ultimately to actually use the energy that's stored in skin mechanically as elastic energy and recover that during the operation of the device,” said Matthew Flavin, the paper’s first author. “Just like stretching a rubber band, compressing the elastic skin stores energy. We can then reapply that energy while we're delivering sensory feedback, and that was ultimately the basis for how we create the created this really energy-efficient system.”

At the time of the research, Flavin was a postdoctoral researcher in Rogers’ lab. Now, he is an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Sensory substitution

To test the device, the researchers blindfolded healthy subjects to test their abilities to avoid objects in their path, change foot placement to avoid injury and alter their posture to improve balance.

One experiment involved a subject navigating a path through obstructing objects. As the subject approached an object, the device delivered feedback in the form of light intensity in its upper right corner. As the person moved nearer to the object, the feedback became more intense, moving closer to the center of the device.

With only a short period of training, subjects using the device were able to change behavior in real time. By substituting visual information with mechanical, the device “would operate very similarly to how a white cane would, but it's integrating more information than someone would be able to get with a more common aid,” Flavin said.

“As one of several application examples, we show that this system can support a basic version of ‘vision’ in the form of haptic patterns delivered to the surface of the skin based on data collected using the 3D imaging function (LiDAR) available on smartphones,” Rogers said. “This sort of ‘sensory substitution’ provides a primitive, but functionally meaningful, sense of one’s surroundings without reliance on eyesight — a capability useful for individuals with vision impairments.”

The title of the study is “Bioelastic state recovery for haptic sensory substitution.”

END

About The Study: In this randomized clinical trial assessing simultaneous vs sequential administration of mRNA COVID-19 and inactivated influenza vaccines, reactogenicity was comparable in both groups. These findings support the option of simultaneous administration of these vaccines.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Emmanuel B. Walter, MD, MPH, email chip.walter@duke.edu.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.43166)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other ...

About The Study: This retrospective cohort study with an extended follow-up period found associations between COVID-19 and the long-term risk of various autoimmune and autoinflammatory connective tissue disorders. Long-term monitoring and care of patients is crucial after COVID-19, considering demographic factors, disease severity, and vaccination status, to mitigate these risks.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Solam Lee, MD, PhD, email solam@yonsei.ac.kr.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website ...

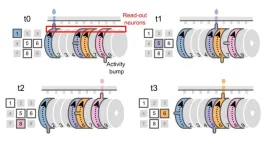

Mount Sinai researchers have discovered for the first time a neural mechanism for memory integration that stretches across both time and personal experience. These findings, reported in Nature, demonstrate how memories stored in neural ensembles in the brain are constantly being updated and reorganized with salient information, and represent an important step in deciphering how our memories stay current with the most recently available information. This discovery could have important implications for better understanding adaptive memory processes ...

The atoms of amorphous solids like glass have no ordered structure; they arrange themselves randomly, like scattered grains of sand on a beach. Normally, making materials amorphous — a process known as amorphization — requires considerable amounts of energy. The most common technique is the melt-quench process, which involves heating a material until it liquifies, then rapidly cooling it so the atoms don’t have time to order themselves in a crystal lattice.

Now, researchers ...

Ghent, 7 November 2024 – Scientists have uncovered how certain E. coli bacteria in the gut promote colon cancer by binding to intestinal cells and releasing a DNA-damaging toxin. The study, published in Nature, sheds light on a new approach to potentially reduce cancer risk. The study was performed by the teams of Prof. Lars Vereecke (VIB-UGent Center for Inflammation Research) and Prof. Han Remaut (VIB-VUB Center for Structural Biology).

Bacteria and colon cancer

Colon cancer ranks as the third most prevalent and deadliest type of cancer. Alarmingly, its incidence is rising, particularly ...

Neuroscientists have discovered brain cells that form multiple coordinate systems to tell us “where we are” in a sequence of behaviours. These cells can play out different sequences of actions, just like a music box can be configured to play different sequences of tones. The findings help us understand the algorithms used by the brain to flexibly generate complex behaviours, such as planning and reasoning, and might be useful in understanding how such processes go wrong in psychiatric ...

Some patients being treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, a type of cancer immunotherapy, develop a dangerous form of heart inflammation called myocarditis. Researchers led by physicians and scientists at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), a founding member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system, have now uncovered the immune basis of this inflammation. The team identified changes in specific types of immune and stromal cells in the heart that underlie myocarditis and pinpointed factors in the blood that may indicate ...

Families purchased more school lunches and breakfasts the year after the federal government toughened nutritional standards for school meals. A new University of California, Davis, study suggests that families turned to school lunches after the Obama administration initiative was in effect to save time and money and take advantage of more nutritious options.

Researchers looked at the purchasing habits of nearly 8,000 U.S. households over two years — one year before and after the change in standards. The results have important implications for policymakers and researchers, but also food manufacturers and retailers, researchers said.

The study, ...

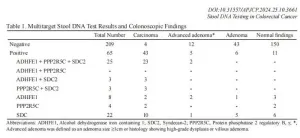

A recent prospective cross-sectional study in Thailand demonstrates that multitarget stool DNA testing is highly sensitive and specific for detecting colorectal cancer (CRC) among Thai individuals. Researchers believe that this testing method could serve as a viable non-invasive alternative to colonoscopy, especially in settings where colonoscopy is less accessible or less accepted by patients.

This study was conducted by BGI Genomics in 2023, in collaboration with Professor Varut Lohsiriwat’s team from the Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Thailand. ...

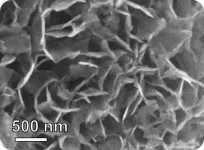

Exhaled breath contains chemical clues to what’s going on inside the body, including diseases like lung cancer. And devising ways to sense these compounds could help doctors provide early diagnoses — and improve patients’ prospects. In a study in ACS Sensors, researchers report developing ultrasensitive, nanoscale sensors that in small-scale tests distinguished a key change in the chemistry of the breath of people with lung cancer. November is Lung Cancer Awareness Month.

People breathe out many gases, such as water vapor and carbon dioxide, as well as other airborne compounds. Researchers ...