(Press-News.org) The atoms of amorphous solids like glass have no ordered structure; they arrange themselves randomly, like scattered grains of sand on a beach. Normally, making materials amorphous — a process known as amorphization — requires considerable amounts of energy. The most common technique is the melt-quench process, which involves heating a material until it liquifies, then rapidly cooling it so the atoms don’t have time to order themselves in a crystal lattice.

Now, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania School of Engineering and Applied Science (Penn Engineering), the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have developed a new method for amorphizing at least one material — wires made of indium selenide, or In2Se3 — that requires as little as one billion times less power density, a result described in a new paper in Nature. This advancement could unlock wider applications for phase-change memory (PCM) — a promising memory technology that could transform data storage in devices from cell phones to computers.

In PCM, information is stored by switching the material between amorphous and crystalline states, functioning like an on/off switch. However, large-scale commercialization has been limited by the high power needed to create these transformations. "One of the reasons why phase-change memory devices haven’t reached widespread use is due to the energy required,” says Ritesh Agarwal, Srinivasa Ramanujan Distinguished Scholar and Professor in Materials Science and Engineering (MSE) at Penn Engineering and one of the paper’s senior authors.

For more than a decade, Agarwal’s group has studied alternatives to the melt-quench process, following their 2012 discovery that electrical pulses can amorphize alloys of germanium, antimony and tellurium without needing to melt the material.

Several years ago, as part of those efforts, one of the new paper’s first authors, Gaurav Modi, then a doctoral student in MSE at Penn Engineering, began experimenting with indium selenide, a semiconductor with several unusual properties: it is ferroelectric, meaning it can spontaneously polarize, and piezoelectric, meaning that mechanical stress causes it to generate an electric charge and, conversely, that an electric charge deforms the material.

Modi discovered the new method essentially by accident. He was running a current through In2Se3 wires when they suddenly stopped conducting electricity. Upon closer examination, long stretches of the wires had amorphized. “This was extremely unusual,” says Modi. “I actually thought I might have damaged the wires. Normally, you would need electrical pulses to induce any kind of amorphization, and here a continuous current had disrupted the crystalline structure, which shouldn’t have happened.”

Untangling that mystery took the better part of three years. Agarwal shipped samples of the wires to one of his former graduate students, Pavan Nukala, now an Assistant Professor at IISc and member of the school’s Centre for Nano Science and Engineering (CeNSE) and one of the paper’s other senior authors. “Over the past few years we have developed a suite of in situ microscopy tools here at IISc. It was time to put them to test — we had to look very, very carefully to understand this process,” says Nukala. “We learned that multiple properties of In2Se3 — the 2D aspect, the ferroelectricity and the piezoelectricity — all come together to design this ultralow energy pathway for amorphization through shocks.”

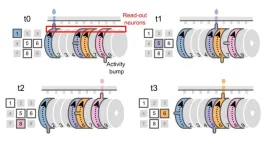

Ultimately, the researchers found that the process resembles both an avalanche and an earthquake. At first, tiny sections — measured in billionths of a meter — within the In2Se3 wires begin to amorphize as electric current deforms them. Due to the wires’ piezoelectric properties and layered structure, the current nudges portions of these layers into unstable positions, like the subtle shifting of snow at the top of a mountain.

When a critical point is reached, this movement triggers a rapid spread of deformation throughout the wire. The distorted regions collide, producing a sound wave that moves through the material, similar to how seismic waves travel through the earth’s crust during an earthquake.

This sound wave, technically known as an “acoustic jerk,” drives additional deformation, linking numerous small amorphous areas into a single one measured in micrometers — thousands of times larger than the original areas — just like an avalanche gathering momentum down a mountainside. “It’s just goosebump stuff to see all these phenomena interacting across different length scales at once,” says Shubham Parate, an IISc doctoral student and co-first author of the paper.

The collaborative effort to understand the process has created fertile ground for future discoveries. “This opens up a new field on the structural transformations that can happen in a material when all these properties come together. The potential of these findings for designing low-power memory devices are tremendous,” says Agarwal.

This study was conducted at the University of Pennsylvania School of Engineering and Applied Science, the Indian Institute of Science and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and supported by the U.S. Office of Naval Research Multidisciplinary University Research Initiatives Program (N00014-17-1-2661), the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) Future of Semiconductors competition (#2328743), the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA9550-23-1-0189), the NSF Materials Research Science and Engineering Centers Division of Materials Research (MRSEC/DMR-2309043), and the Anusandhan National Research Foundation Science and Engineering Research Board (CRG/2022/003506) from the Government of India, as well as the facilities at CeNSE and the Advanced Facility for Microscopy and Microanalysis (AFMM), IISc, and the democratized system of usage.

Additional co-authors include Anudeep Tullibilli of IISc; Choah Kwon and Ju Li of MIT; and Andrew C. Meng, Utkarsh Khandelwal, James Horwath, Peter K. Davies and Eric A. Stach of Penn Engineering.

END

Breakthrough in energy-efficient avalanche-based amorphization could revolutionize data storage

2024-11-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists discover how specific E. coli bacteria drive colon cancer

2024-11-06

Ghent, 7 November 2024 – Scientists have uncovered how certain E. coli bacteria in the gut promote colon cancer by binding to intestinal cells and releasing a DNA-damaging toxin. The study, published in Nature, sheds light on a new approach to potentially reduce cancer risk. The study was performed by the teams of Prof. Lars Vereecke (VIB-UGent Center for Inflammation Research) and Prof. Han Remaut (VIB-VUB Center for Structural Biology).

Bacteria and colon cancer

Colon cancer ranks as the third most prevalent and deadliest type of cancer. Alarmingly, its incidence is rising, particularly ...

Brain acts like music box playing different behaviours

2024-11-06

Neuroscientists have discovered brain cells that form multiple coordinate systems to tell us “where we are” in a sequence of behaviours. These cells can play out different sequences of actions, just like a music box can be configured to play different sequences of tones. The findings help us understand the algorithms used by the brain to flexibly generate complex behaviours, such as planning and reasoning, and might be useful in understanding how such processes go wrong in psychiatric ...

Study reveals how cancer immunotherapy may cause heart inflammation in some patients

2024-11-06

Some patients being treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, a type of cancer immunotherapy, develop a dangerous form of heart inflammation called myocarditis. Researchers led by physicians and scientists at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), a founding member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system, have now uncovered the immune basis of this inflammation. The team identified changes in specific types of immune and stromal cells in the heart that underlie myocarditis and pinpointed factors in the blood that may indicate ...

More families purchased school meals after federal nutrition policies enacted

2024-11-06

Families purchased more school lunches and breakfasts the year after the federal government toughened nutritional standards for school meals. A new University of California, Davis, study suggests that families turned to school lunches after the Obama administration initiative was in effect to save time and money and take advantage of more nutritious options.

Researchers looked at the purchasing habits of nearly 8,000 U.S. households over two years — one year before and after the change in standards. The results have important implications for policymakers and researchers, but also food manufacturers and retailers, researchers said.

The study, ...

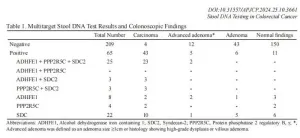

Research proves stool DNA as non-invasive alternative for colorectal cancer screening in Thailand

2024-11-06

A recent prospective cross-sectional study in Thailand demonstrates that multitarget stool DNA testing is highly sensitive and specific for detecting colorectal cancer (CRC) among Thai individuals. Researchers believe that this testing method could serve as a viable non-invasive alternative to colonoscopy, especially in settings where colonoscopy is less accessible or less accepted by patients.

This study was conducted by BGI Genomics in 2023, in collaboration with Professor Varut Lohsiriwat’s team from the Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Thailand. ...

Detecting evidence of lung cancer in exhaled breath

2024-11-06

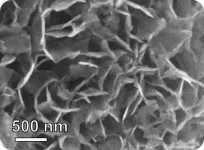

Exhaled breath contains chemical clues to what’s going on inside the body, including diseases like lung cancer. And devising ways to sense these compounds could help doctors provide early diagnoses — and improve patients’ prospects. In a study in ACS Sensors, researchers report developing ultrasensitive, nanoscale sensors that in small-scale tests distinguished a key change in the chemistry of the breath of people with lung cancer. November is Lung Cancer Awareness Month.

People breathe out many gases, such as water vapor and carbon dioxide, as well as other airborne compounds. Researchers ...

A joint research team of Korea University College of Medicine announced the world's first single-port robotic thymectomy comparative results

2024-11-06

A Joint research team (Prof. Jun-hee Lee, Hyun-koo Kim, Jin-Wook Hwang, Jae-Ho Chung, the Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Korea University College of Medicine) Announced the world's first compartive results of single-port robotic thymectomy using the single-port robotic system.

The team compared and analyzed the perioperative outcomes of 110 cases of robotic thymectomy using the single-port robotic system and conventional video-assisted thoracic surgery(VATS) thymectomy from November 2018 to May 2024. The results showed that all robotic thymectomy performed were successfully ...

National Mental Health Institute awards CAD 45 million to develop mental health treatments

2024-11-06

One out of 100 people will experience a psychotic episode in their lifetime, and these usually appear in late adolescence or early adulthood. A Canada-US team consisting of Sylvain Bouix, from École de technologie supérieure (ÉTS), Martha E. Shenton and Ofer Pasternak, from the Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Harvard University), and René Kahn, from Mount Sinai Hospital (New York) has just received US $33 million in funding—the equivalent of CAD 45 million—over five years from the National Institute of Mental Health ...

Washington coast avian flu outbreak devastated Caspian terns, jumped to seals

2024-11-06

PULLMAN, Wash. – An epidemiological study found that 56% of a large breeding colony of Caspian terns died from a 2023 outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza at Rat Island in Washington state. Since then, no birds have successfully bred on the island, raising concerns that the outbreak may have had a significant impact on an already declining Pacific-coast population.

As part of the study, a team including Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) as well as Washington State University researchers also documented that the avian flu virus H5N1was transmitted to harbor seals for the first time in the northeastern ...

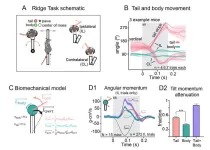

Mice tails whip up new insights into balance and neurodegenerative disease research

2024-11-06

Why do mice have tails?

The answer to this is not as simple as you might think. New research from the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) has shown that there’s more to the humble mouse tail than previously assumed. Using a novel experimental setup involving a tilting platform, high-speed videography and mathematical modelling, scientists have demonstrated how mice swing their tails like a whip to maintain balance – and these findings can help us better understand balance issues in humans, paving the way for spotting and treating neurodegenerative diseases like multiple ...