(Press-News.org) University of Maryland entomologists uncovered a unique relationship between two species of fungi known for their ability to invade, parasitize and kill insects efficiently. Instead of violently competing for the spoils of war, the two fungi peacefully cooperate and share their victims.

The findings, published in the journal Public Library of Science (PLOS) Pathogens on November 7, 2024, offer insight into some of the biggest evolutionary successes in nature’s history, according to study co-authors Raymond St. Leger, a Distinguished University Professor of Entomology, and entomology Ph.D. candidate Huiyu Sheng.

“It’s not survival of the fittest in the way we often think of. Sometimes, it’s the survival of those who can just get along,” St. Leger explained. “Rather than wiping each other out, these fungi apparently evolved sophisticated ways of coexisting—and we are just beginning to understand that balance.”

The study focused on two species of a fungal genus called Metarhizium, which can be found in soil around the world. Members of this fungal group protect plants from damaging abiotic stresses (such as drought or poor nutrients) and harmful insects.

“These microorganisms have been called keystone species because they play crucial roles in both plant health and natural insect population control,” St. Leger said. “Our findings may help explain their extraordinary success in ecosystems worldwide.”

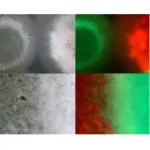

Using advanced imaging techniques with fluorescent proteins that made the fungi glow red or green, the scientists observed how the fungi interacted when colonizing (infecting, spreading inside and eventually killing) insects. Rather than one strain dominating and excluding the other, the team found that the fungi neatly divided their territory amongst themselves—quite literally.

When colonizing pests, the two fungal strains showed an uncanny ability to split up their victim. One strain tacitly invaded the front segments of an insect host, while the other colonized the back segments, with the two invaded territories distinctly separated by a remarkably sharp dividing line between them. This pattern held true whether the chosen victim was a large caterpillar weighing ten grams or a tiny fly weighing less than a single milligram.

“The sharpness of the delineation between where one fungus starts and the other ends looks quite bizarre,” St. Leger noted. “The borders separating the segments from each other are inexplicably clear.”

So, why does this cooperation exist? The researchers believe each strain of fungus adapted their own unique specialties and niches over time, allowing them to partition limited resources.

“It’s becoming clear that sometimes the key to evolutionary success isn’t outcompeting your rivals—it’s learning to share,” St. Leger said.

But just how these fungi orient themselves within their hosts and how they communicate their territorial division remain mysteries. The researchers hope to investigate the mechanisms responsible for these host-sharing strategies and open up new avenues of research on how they could be used to bolster both food security and Earth’s biodiversity.

Understanding how different fungal species interact could help scientists and agriculturalists develop better biological pest control methods and strategies to promote plant growth. St. Leger notes that the fungi already show incredible promise in protecting plants from mercury poisoning, enhancing crop growth and killing disease-spreading insects.

“These fungi have shown that they are very adaptable,” he said. “They’ve been doing this for a very long period of time and have thus evolved an arsenal of novel, sophisticated and subtle tricks. They are also very easy to genetically engineer so their applications are limited only by your imagination.”

###

The paper, “Metarhizium fight club: within-host competitive exclusion and resource partitioning,” was published in the scientific journal Public Library of Science (PLOS) Pathogens on November 7, 2024.

END

Not everyone responds equally well to treatments for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). What will work for individual patients involves trial and error during the treatment process. Now, a team of researchers led by Charité – Universitätsmedizin, in collaboration with colleagues in Berlin and Bonn, has succeeded in identifying a biomarker that indicates whether or not treatment with a certain medication called an immunomodulator will be successful. Writing in the journal Gastroenterology,* the researchers note that this will permit more targeted use of the therapy.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) takes multiple ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — A University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign study is the first to describe an electrochemical strategy to capture, concentrate and destroy mixtures of diverse chemicals known as PFAS — including the increasingly prevalent ultra-short-chain PFAS — from water in a single process. This new development is poised to address the growing industrial problem of contamination with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, particularly in semiconductor manufacturing.

A previous U. of I. study showed that short- and long-chain PFAS can be removed from water using electrochemically driven adsorption, referred to as ...

Researchers Identify Reduction in Heart Failure-Related Risk Factors following Metabolic Surgery

Recent study suggests that metabolic surgery for patients with heart failure can reduce dependency on oral diuretics, which are used to manage heart failure symptoms

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

November 7, 2024

BATON ROUGE – Pennington Biomedical Research Center researchers at the Metamor Institute, along with colleagues from Our Lady of the Lake and LSU Health-New Orleans, have recently determined that metabolic surgery on patients with heart failure can result in a reduction in the need for oral diuretics, which are used to manage symptoms such as venous and ...

For more than 50 years, as a leading pioneer of preventive medicine and the “father of aerobics,” Kenneth H. Cooper, M.D., has revolutionized health and fitness worldwide. Similarly, the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC) has long been dedicated to education, patient care and research. Today (Nov. 4) TTUHSC officially welcomed The Cooper Institute as part of its organization with a special presentation and unveiling of its new name – the Kenneth H. Cooper Institute at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center.

The Cooper ...

In 79 AD, Mount Vesuvius experienced one of its most significant eruptions, burying the Roman city of Pompeii and its inhabitants under a thick layer of small stones and ash known as lapilli. Many of Pompeii's inhabitants lost their lives as their homes collapsed under the weight of the lapilli raining down from many kilometres above. Those who survived the initial phase of the eruption eventually succumbed to the dangerous pyroclastic flows. This fast-moving stream of hot gas and volcanic matter instantly enveloped their bodies in a solid layer of ash, effectively preserving their bodies, including their features.

Since the 1800s, casts had been made by pouring plaster into the ...

In 79 CE, the active volcanic system in southern Italy known as Somma-Vesuvius erupted, burying the small Roman town of Pompeii and everyone in it. The “Pompeii eruption” covered everything in a layer of ash that preserved many of the bodies. Now, ancient DNA collected from the famed body casts alters the history that’s been written since the once forgotten town’s rediscovery in the 1700s. As reported on November 7, 2024, in Current Biology, the DNA evidence shows that individuals’ sexes and family relationships don’t match ...

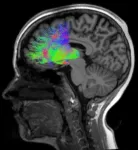

Scientists have known for decades that the classic symptoms of schizophrenia, such as jumping to conclusions or difficulty adjusting to new information, can be attributed to poor communication between the cerebral cortex and the thalamus, known as the brain’s central switchboard. By measuring brain cell activity between these two regions as volunteers completed ambiguous tasks, a team of Tufts University School of Medicine and Vanderbilt University School of Medicine researchers found a way to use someone’s sensitivity to uncertainty as a diagnostic tool.

In a study published November 7 in the journal ...

Annual emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) from private aviation increased by 46% between 2019 and 2023, according to an analysis published in Communications Earth & Environment. The results also show that some individuals who regularly use private aviation may produce almost 500 times more CO2 in a year than the average individual, and that there were significant emissions peaks around certain international events, including COP 28 and the 2022 FIFA World Cup.

Private aviation is highly energy-intensive, emitting significantly more CO2 per passenger than commercial flights, but is used by approximately 0.003% ...

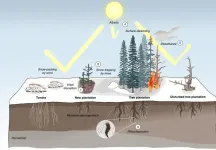

Tree planting has been widely touted as a cost-effective way of reducing global warming, due to trees’ ability to store large quantities of carbon from the atmosphere. But, writing in the journal Nature Geoscience, an international group of scientists argue that tree planting at high latitudes will accelerate, rather than decelerate, global warming.

As the climate continues to warm, trees can be planted further and further north, and large-scale tree-planting projects in the Arctic have been championed by governments and ...

Genes contain instructions for making proteins, and a central dogma of biology is that this information flows from DNA to RNA to proteins. But only two percent of the human genome actually encodes proteins; the function of the remaining 98 percent remains largely unknown.

One pressing problem in human genetics is to understand what these regions of the genome do—if anything at all. Historically, some have even referred to these regions as “junk.”

Now, a new study in Cell finds that some noncoding RNAs are not, in fact, junk—they are functional and play an important role in our cells, including in cancer and human development. Using CRISPR technology that ...