(Press-News.org) EMBARGOED: Until 3 p.m. ET on Monday, Nov. 11, 2024

Contacts:

Laura Snider, NSF NCAR and UCAR Manager of Science Communications

lsnider@ucar.edu

303-827-1502

David Hosansky, NSF NCAR and UCAR Manager of Media Relations

hosansky@ucar.edu

720-470-2073

Like the Earth, the Sun likely has swirling polar vortices, according to new research led by the U.S. National Science Foundation National Center for Atmospheric Research (NSF NCAR). But unlike on Earth, the formation and evolution of these vortices are driven by magnetic fields.

The findings, published [xxxxxx] in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), have implications for our basic understanding of the Sun’s magnetism and the solar cycle, which could in turn improve our ability to predict disruptive space weather. The new research also paints a picture of what we might expect to see at the solar poles during future missions to the Sun and provides information that could be useful in planning the timing of such missions.

“No one can say for certain what is happening at the solar poles,” said NSF NCAR senior scientist Mausumi Dikpati, who led the new study. “But this new research gives us an intriguing look at what we might expect to find when we are able, for the first time, to observe the solar poles.”

The research was funded by NSF and NASA with supercomputing resources made available on NSF NCAR’s Cheyenne and Derecho systems.

A mystery at the Sun’s poles

The likely presence of some kind of polar vortices on the Sun does not come as a surprise. These spinning formations develop in fluids that surround a rotating body due to the Coriolis force, and they have been observed on the majority of planets in our solar system. On Earth, a vortex spins high in the atmosphere around both the north and south poles. When those vortices are stable, they keep frigid air locked at the poles, but when they weaken and become unstable, they allow that cold air to seep toward the equator, causing cold air outbreaks in the midlatitudes.

NASA’s Juno mission returned breathtaking images of polar vortices on Jupiter, showing eight tightly packed swirls around the gas giant’s north pole and five around its south. The polar vortices on Saturn, seen by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, are hexagonally shaped in the north pole and more circular in the south. These differences offer scientists clues into the makeup and dynamics of each planet’s atmosphere.

Polar vortices have also been observed in Mars, Venus, Uranus, Neptune, and Saturn’s moon Titan, so in some ways, the fact that the Sun (also a rotating body surrounded by a fluid) would have such features may be obvious. But the Sun is also fundamentally different from the planets and moons that possess atmospheres: the plasma “fluid” that surrounds the Sun is magnetic.

How that magnetism might influence the formation and evolution of solar polar vortices — or whether they form at all — is a mystery because humanity has never sent a mission into space that can observe the Sun’s poles. In fact our observations of the Sun are limited to views of the face of the Sun as it points toward Earth and only offers hints at what might be transpiring at the poles.

A ring of vortices tied to the solar cycle

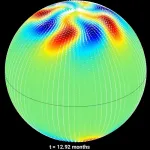

Since we have never observed the Sun’s poles, the science team relied on computer models to fill in the blanks about what solar polar vortices might look like. What they found is that the Sun is likely to indeed have a unique pattern of polar vortices that evolves as the solar cycle unfolds and depends on the strength of any particular cycle.

In the simulations, a tight ring of polar vortices forms at around 55 degrees latitude — the equivalent of Earth’s Arctic circle — at the same time that a phenomenon called the “rush to the poles” begins. At the maximum of each solar cycle, the magnetic field at the Sun’s poles disappears and is replaced with a magnetic field of opposite polarity. This flip-flop is preceded by a “rush to the poles” when the field of opposite polarity begins to travel from about 55 degrees in latitude poleward.

After forming, the vortices head toward the poles in a tightening ring, shedding vortices as the circle closes, eventually leaving only a pair of vortices directly abutting the poles before they disappear altogether at solar maximum. How many vortices form and their configuration as they move toward the poles changes with the strength of the solar cycle.

These simulations offer a missing piece to the puzzle of how the Sun’s magnetic field behaves near the poles and may help answer some fundamental questions about the Sun’s solar cycles. For example, in the past many scientists have used the strength of the magnetic field that “rushes to the poles” as a proxy for how strong the upcoming solar cycle is likely to be. But the mechanism for how those things might connect, if at all, is not clear.

The simulations also offer information that may be used for planning future missions to observe the Sun. Namely, the results indicate that some form of polar vortices should be observable during all parts of the solar cycle except during the solar maximum.

“You could launch a solar mission, and it could arrive to observe the poles at completely the wrong time,” said Scott McIntosh, vice president of space operations for Lynker and a co-author of the paper.

The Solar Orbiter, a cooperative mission between NASA and the European Space Agency, could give researchers their first glimpse of the solar poles, but the first look will be close to solar maximum. The authors note that a mission designed to observe the poles and to give researchers multiple, simultaneous viewpoints of the Sun could help them answer many long-held questions about the Sun’s magnetic fields.

“Our conceptual boundary now is that we are operating with only one viewpoint,” McIntosh said. “To make significant progress, we must have the observations we need to test our hypotheses and confirm whether simulations like these are correct.”

About the study:

Title: A Magnetohydrodynamic Mechanism for the Formation of Solar Polar Vortices

Authors: M. Dikpati, B. Raphaldini, S. W. McIntosh, M. Korsos, G. A. Guerrero, P. A. Gilman

Journal: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

This material is based upon work supported by the NSF National Center for Atmospheric Research, a major facility sponsored by the U.S. National Science Foundation and managed by the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material do not necessarily reflect the views of NSF.

END

Swirling polar vortices likely exist on the Sun, new research finds

Model simulations offer insights into the fundamental properties of the solar magnetic field

2024-11-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Protein degradation strategy offers new hope in cancer therapy

2024-11-11

RIVERSIDE, Calif. -- In drug discovery, targeted protein degradation is a method that selectively eliminates disease-causing proteins. A University of California, Riverside team of scientists has used a novel approach to identify protein degraders that target Pin1, a protein involved in pancreatic cancer development.

The team reports today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that it has designed agents that not only bind tightly to Pin1 but are designed to cause its destabilization and cellular ...

Mental fatigue leads to loss of self-control by putting brain areas to sleep

2024-11-11

Prolonged mental fatigue can wear down brain areas crucial for the individual ability to self-control, and cause people to behave more aggressively.

In a new multidisciplinary study published in the PNAS, a group of researchers from neuroscience and economics at the IMT School of Advanced Studies Lucca links the debated concept of "ego depletion", that is to say the diminution of willpower caused by previous exploitation of it, to physical changes in the areas that govern executive functions in the brain. In particular, the ...

Was ‘Snowball Earth’ a global event? New study delivers best proof yet

2024-11-11

Geologists have uncovered strong evidence from Colorado that massive glaciers covered Earth down to the equator hundreds of millions of years ago, transforming the planet into an icicle floating in space.

The study, led by the University of Colorado Boulder, is a coup for proponents of a long-standing theory known as Snowball Earth. It posits that from about 720 to 635 million years ago, and for reasons that are still unclear, a runaway chain of events radically altered the planet’s climate. Temperatures plummeted, and ice sheets that may have been several miles thick crept over every inch of Earth’s surface.

“This study presents the first physical evidence ...

Scientists issue call to action underlining importance of microbial solutions to tackle climate crisis

2024-11-11

Ahead of COP29, Applied Microbiology International (AMI) has partnered with leading global scientific organisations to issue a unified call to action, spotlighting microbial solutions as pivotal in combating climate change.

In a strategic publication, released in multiple high-impact scientific journals at once, the joint paper advocates for the establishment of a global science-driven climate task force. This initiative aims to expedite the deployment of microbiome technologies, providing stakeholders worldwide with access to effective and immediate solutions.

Signatories of the paper, ‘Microbial solutions must be deployed against the climate catastrophe’ ...

Ochsner Transplant Institute among site collaborators in New England Journal of Medicine HIV-to-HIV kidney transplant study

2024-11-11

NEW ORLEANS – The Ochsner Transplant Institute served as one of 26 U.S. transplant centers collaborating in an HIV-to-HIV kidney transplant study published by The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). The article, Safety of Kidney Transplantation from Donors with HIV, details findings supporting HIV-to-HIV kidney transplants as safe and just as effective as those using organs from donors without HIV.

Human immunodeficiency virus, commonly known as HIV, attacks cells in the body that fight infection and there is currently no known cure. In the U.S.,1.2 million people are living with HIV. According to the National ...

Scientists call for global action on microbial climate solutions

2024-11-11

Washington, D.C. — Nov. 11, 2024 — Today, leaders from scientific societies, institutions and publishing bodies issued an urgent call for the global community and governments to take immediate and decisive emergency climate action. This appeal is made through an editorial published in mSystems, released on the opening day of the 2024 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP29). Key contributors to this initiative include Virginia Miller, past president of the American Society for Microbiology (ASM); Jack Gilbert, Editor-in-Chief of mSystems; and Jay Lennon, ...

New antibody could be promising cancer treatment

2024-11-11

Researchers at Uppsala University and KTH Royal Institute of Technology have developed a new form of precision medicine, an antibody, with the potential to treat several types of cancer. Researchers have managed to combine three different functions in the antibody, which together strongly amplify the effect of T cells on the cancer tumour. The study has been published in Nature Communications.

Researchers have developed a unique type of antibody that both targets and delivers a drug package via the antibody itself, while simultaneously activating the immune system (“3-in-1 design”) for personalised immunotherapy treatments.

“We ...

The public implications of private substitutes for electric grid reliability

2024-11-11

Climate change events have, in recent years, placed increasing strain on public electrical grids in the United States. In response to this vulnerability, some consumers are turning to private alternatives to the electric utility, like generators and batteries. A new paper in the Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists studies who adopts these private alternatives and how adoption responds to grid failures. The paper also studies how public electric grid reliability may change due to this proliferation and how these changes will affect the wellbeing of all households.

In ...

Religiosity, spirituality, and meaning-making generally associated with lower suicidality

2024-11-11

November 11, 2024 — All aspects of religiosity, spirituality, and meaning-making (R/S/M) relate to suicidality in people with a psychiatric diagnosis or a recent suicide attempt, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis published in Harvard Review of Psychiatry, part of the Lippincott portfolio from Wolters Kluwer.

"Protective dimensions seemed to exert relatively stable effects across different religions and life views," Bart van den Brink, MD, PhD, of the Department of ...

Eife studying legal surveillance as social determinant of health

2024-11-11

Erin Eife, Assistant Professor, Criminology, Law and Society, College of Humanities and Social Sciences (CHSS), received funding for the project: “Surveillance as a Social Determinant of Health: Understanding the Impact of Pending Charges on Health Outcomes.”

Eife will conduct this research under the advisement of Evan Lowder, Associate Professor, Criminology, Law and Society, College of Humanities and Social Sciences (CHSS), and Lauren Brinkley-Rubinstein, Associate Professor in the Department of Population Health Sciences at Duke University.

Eife aims to produce knowledge about ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Massive-scale spatial multiplexing with 3D-printed photonic lanterns achieved by researchers

Younger stroke survivors face greater concentration, mental health challenges — especially those not employed

From chatbots to assembly lines: the impact of AI on workplace safety

Low testosterone levels may be associated with increased risk of prostate cancer progression during surveillance

Analysis of ancient parrot DNA reveals sophisticated, long-distance animal trade network that pre-dates the Inca Empire

How does snow gather on a roof?

Modeling how pollen flows through urban areas

Blood test predicts dementia in women as many as 25 years before symptoms begin

Female reproductive cancers and the sex gap in survival

GLP-1RA switching and treatment persistence in adults without diabetes

Gnaw-y by nature: Researchers discover neural circuit that rewards gnawing behavior in rodents

Research alert: How one receptor can help — or hurt — your blood vessels

Lamprey-inspired amphibious suction disc with hybrid adhesion mechanism

A domain generalization method for EEG based on domain-invariant feature and data augmentation

Bionic wearable ECG with multimodal large language models: coherent temporal modeling for early ischemia warning and reperfusion risk stratification

JMIR Publications partners with the University of Turku for unlimited OA publishing

Strange cosmic burst from colliding galaxies shines light on heavy elements

Press program now available for the world's largest physics meeting

New release: Wiley’s Mass Spectra of Designer Drugs 2026 expands coverage of emerging novel psychoactive substances

Exposure to life-limiting heat has soared around the planet

New AI agent could transform how scientists study weather and climate

New study sheds light on protein landscape crucial for plant life

New study finds deep ocean microbes already prepared to tackle climate change

ARLIS partners with industry leaders to improve safety of quantum computers

Modernization can increase differences between cultures

Cannabis intoxication disrupts many types of memory

Heat does not reduce prosociality

Advancing brain–computer interfaces for rehabilitation and assistive technologies

Detecting Alzheimer's with DNA aptamers—new tool for an easy blood test

Chinese Neurosurgical Journal study develops radiomics model to predict secondary decompressive craniectomy

[Press-News.org] Swirling polar vortices likely exist on the Sun, new research findsModel simulations offer insights into the fundamental properties of the solar magnetic field