(Press-News.org) Highlights:

The Atacama Desert is one of the most extreme habitats on Earth.

Atacama surface soil samples include a mix of DNA from inside and outside living cells.

A new technique allows researchers to separate external and internal DNA to identify microbes colonizing this hostile environment.

This approach for analyzing microbial communities could potentially be applied to other hostile environments, like those on other planets.

Washington, D.C.—The Atacama Desert, which runs along the Pacific Coast in Chile, is the driest place on the planet and, largely because of that aridity, hostile to most living things. Not everything, though—studies of the sandy soil have turned up diverse microbial communities. Studying the function of microorganisms in such habitats is challenging, however, because it’s difficult to separate genetic material from the living part of the community from genetic material of the dead.

A new separation technique can help researchers focus on the living part of the community. This week in Applied and Environmental Microbiology, an international team of researchers describes a new way to separate extracellular (eDNA) from intracellular (iDNA) genetic material. The method provides better insights into microbial life in low-biomass environments, which was previously not possible with conventional DNA extraction methods, said Dirk Wagner, Ph.D., a geomicrobiologist at the GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences in Potsdam, who led the study.

The microbiologists used the novel approach on Atacama soil samples collected from the desert along a west-to-east swath from the ocean’s edge to the foothills of the Andes mountains. Their analyses revealed a variety of living and possibly active microbes in the most arid areas. A better understanding of eDNA and iDNA, Wagner said, can help researchers probe all microbial processes.

“Microbes are the pioneers colonizing this kind of environment and preparing the ground for the next succession of life,” Wagner said. These processes, he said, aren’t limited to the desert. “This could also apply to new terrain that forms after earthquakes or landslides where you have more or less the same situation, a mineral or rock-based substrate.”

Most commercially available tools for extracting DNA from soils leave a mixture of living, dormant and dead cells from microorganisms, Wagner said. “If you extract all the DNA, you have DNA from living organisms and also DNA that can represent organisms that just died or that died a long time ago.” Metagenomic sequencing of that DNA can reveal specific microbes and microbial processes. However, it requires sufficient good-quality DNA, Wagner added, “which is often the bottleneck in low-biomass environments.”

To remedy that problem, he and his collaborators developed a process for filtering intact cells out of a mixture, leaving behind eDNA genetic fragments left from dead cells in the sediment. It involves multiple cycles of gentle rinsing, he said. In lab tests they found that after 4 repetitions, nearly all the DNA in a sample had been divided into the 2 groups.

When they tested soil from the Atacama Desert, they found Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria in all samples in both eDNA and iDNA groups. That’s not surprising, Wagner said, because the living cells constantly replenish the store of iDNA as they die and degrade. “If a community is really active, then a constant turnover is taking place, and that means the 2 pools should be more similar to each other,” he said. In samples collected from depths of less than 5 centimeters, they found that Chloroflexota bacteria dominated in the iDNA group.

In future work, Wagner said he plans to conduct metagenomic sequencing on the iDNA samples to better understand the microbes at work, and to apply the same approach to samples from other hostile environments. By studying iDNA, he said, “you can get deeper insights into the real active part of the community.”

###

The American Society for Microbiology is one of the largest professional societies dedicated to the life sciences and is composed of over 32,000 scientists and health practitioners. ASM's mission is to promote and advance the microbial sciences.

ASM advances the microbial sciences through conferences, publications, certifications, educational opportunities and advocacy efforts. It enhances laboratory capacity around the globe through training and resources. It provides a network for scientists in academia, industry and clinical settings. Additionally, ASM promotes a deeper understanding of the microbial sciences to diverse audiences.

END

Living microbes discovered in Earth’s driest desert

2024-11-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Artemisinin partial resistance in Ugandan children with complicated malaria

2024-11-14

About The Study: This study found artemisinin partial resistance in Ugandan children with complicated malaria associated with the Pfkelch13 A675V variation and also found suboptimal 28-day efficacy of parenteral artesunate followed by oral artemether/lumefantrine therapy.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Chandy C. John, MD, MS, email chjohn@iu.edu.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jama.2024.22343)

Editor’s Note: Please see the ...

When is a hole not a hole? Researchers investigate the mystery of 'latent pores'

2024-11-14

Sometimes the holes, or pores, in the molecular structure of a chemical only appear in the presence of certain conditions or other ‘guest’ molecules. This affects the field of separation—one of the most important processes in industry—but researchers have only just begun to unravel this phenomenon

Researchers have explored how a particular chemical can selectively trap certain molecules in the cavities of its structure—even though in normal conditions it has no such cavities. This innovative material with now-you-see-them-now-you-don’t holes could lead to more efficient methods for separating ...

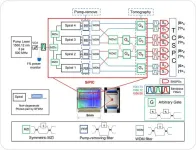

ETRI, demonstration of 8-photon qubit chip for quantum computation

2024-11-14

A group of South Korean researchers has successfully developed an integrated quantum circuit chip using photons (light particles). This achievement is expected to enhance the global competitiveness of the team in quantum computation research.

Electronics and Telecommunications Research Institute (ETRI) announced that they have developed a system capable of controlling eight photons using a photonic integrated-circuit chip. With this system, they can explore various quantum phenomena, such as multipartite entanglement resulting from the interaction of the photons.

ETRI’s extensive research on silicon-photonic quantum ...

Remote telemedicine tool found highly accurate in diagnosing melanoma

2024-11-14

Collecting images of suspicious-looking skin growths and sending them off-site for specialists to analyze is as accurate in identifying skin cancers as having a dermatologist examine them in person, a new study shows.

According to the study authors, the findings add to evidence that such technology could help to reliably address diagnostic and treatment disparities for lower-income populations with limited access to dermatologists. It may also help dermatologists quickly catch cases of melanoma, a serious form of skin cancer that kills more than 8,000 Americans a year.

Their new system, which the researchers call SpotCheck, enables skin cancer specialists ...

New roles in infectious process for molecule that inhibits flu

2024-11-14

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Researchers have identified new roles for a protein long known to protect against severe flu infection – among them, raising the minimum number of viral particles needed to cause sickness.

The protein also helps prevent unfamiliar viruses from mutating after they infect a new host, the study found – meaning its absence during an immune response could enable an animal virus spilled over to people to adapt rapidly to human hosts.

The combined findings by scientists at The Ohio State University add up to potential trouble for people deficient in the protein, called IFITM3 – especially if an avian or swine flu were to gain ...

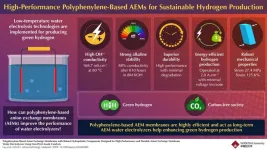

Transforming anion exchange membranes in water electrolysis for green hydrogen production

2024-11-14

Hydrogen is a promising energy source due to its high energy density and zero carbon emissions, making it a key element in the shift toward carbon neutrality. Traditional hydrogen production methods, like coal gasification and steam methane reforming, release carbon dioxide, undermining environmental goals. Electrochemical water splitting, which yields only hydrogen and oxygen, presents a cleaner alternative. While proton exchange membrane (PEM) and alkaline water electrolyzers (AWEs) are available, they face limitations in either cost or efficiency. PEM electrolyzers, for instance, rely on costly platinum group metals (PGMs) as catalysts, whereas ...

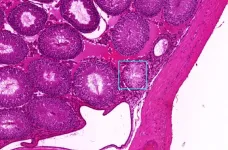

AI method can spot potential disease faster, better than humans

2024-11-14

PULLMAN, Wash. – A “deep learning” artificial intelligence model developed at Washington State University can identify pathology, or signs of disease, in images of animal and human tissue much faster, and often more accurately, than people.

The development, detailed in Scientific Reports, could dramatically speed up the pace of disease-related research. It also holds potential for improved medical diagnosis, such as detecting cancer from a biopsy image in a matter of minutes, a process that typically takes ...

A development by Graz University of Technology makes concreting more reliable, safer and more economical

2024-11-14

Concreting mistakes can be expensive. Concrete poured too quickly often leads to a lack of colour uniformity, irregularities in the structure and uneven surfaces. Particularly in the case of exposed concrete, expensive reworking using concrete cosmetics is then necessary, sometimes a wall may even have to be demolished. In addition, if the fresh concrete rises too quickly in the formwork, there is a certain risk potential for the workers, as this can cause the formwork to break. In their DigiCoPro project, Ralph Stöckl and ...

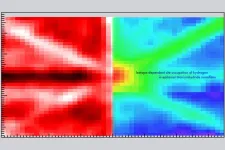

Pinpointing hydrogen isotopes in titanium hydride nanofilms

2024-11-14

Tokyo, Japan – Although it is the smallest and lightest atom, hydrogen can have a big impact by infiltrating other materials and affecting their properties, such as superconductivity and metal-insulator-transitions. Now, researchers from Japan have focused on finding an easy way to locate it in nanofilms.

In a study published recently in Nature Communications, researchers from the Institute of Industrial Science, The University of Tokyo have reported a method for determining the location of hydrogen in nanofilms.

Because they are very small, hydrogen atoms can easily migrate into the framework of other materials. Titanium absorbs hydrogen to give titanium hydrides, making ...

Political abuse on X is a global, widespread, and cross-partisan phenomenon, suggests new study

2024-11-14

A new study suggests that political abuse is a key feature of political communication on social media platform, ‘X’, and whether on the political left or right, it is just as common to see politically engaged users abusing their political opponents, to a similar degree, and with little room for moderates.

While previous research into such online abuse has typically focused on the USA, the current study found that abuse followed a common ally-enemy structure across the nine countries for which there was available data: Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, Turkey, ...