(Press-News.org) The rod-shaped tuberculosis (TB) bacterium, which the World Health Organization has once again ranked as the top infectious disease killer globally, is the first single-celled organism ever observed to maintain a consistent growth rate throughout its life cycle. These findings, reported by Tufts University School of Medicine researchers on November 15 in the journal Nature Microbiology, overturn core beliefs of bacterial cell biology and hint at why the deadly pathogen so readily outmaneuvers our immune system and antibiotics.

"The most basic thing you can study in bacteria is how they grow and divide, yet our study reveals that the TB pathogen is playing by a completely different set of rules compared to easier-to-study model organisms,” said Bree Aldridge, a professor of molecular biology and microbiology at the School of Medicine and a professor of biomedical engineering at the School of Engineering, as well as one of the paper’s co-senior authors along with Ariel Amir of the Weizmann Institute of Science.

TB bacteria are successful at surviving in humans because some parts of the infection can quickly evolve within their host, allowing these outliers to avoid detection or resist treatment. If someone has TB, it takes months of various antibiotics to be cured, and even then, this approach is only successful in 85% of patients. Aldridge and her colleagues hypothesize that gaps in our understanding of the basic biology behind this phenomenon have been holding back the development of more effective treatments.

Getting answers, however, proved to be slow and meticulous work. Postdoctoral fellow Christin (Eun Seon) Chung at the School of Medicine, one of the paper’s first authors, spent three years in a specialized facility equipped to handle high-risk pathogens observing the behavior of individual TB cells. Because TB bacteria double every ~24 hours (compared to 20 minutes for several model bacterial species), Aldridge’s team needed to develop and deploy new microscopy methods to film the microbe over week-long periods. Chung analyzed the footage and tracked each TB bacterium and their progeny manually as they are also notoriously small and prone to move about, so automated analysis could not be used.

These experiments showed that the TB bacterium doesn’t follow expected patterns of cell growth. In other bacterial species, growth is exponential, which means cells grow slower when they are smaller. For TB bacteria, growth rates can be the same whether they are newly born (and small) or far along in their cell cycle and soon to divide.

“This is the first reported organism that can do this,” said Chung. “TB’s behavior challenges fundamental bacterial biology as it’s been thought that ribosomes—which are sites of protein synthesis in the cell—drive cell growth rates, but our work suggests that something else may be happening in TB bacteria that raises new questions about its growth control.”

In addition to reporting that there is extensive variation in growth behaviors among the individual bacterial cells, the team discovered another new growth behavior of TB bacteria: they can also begin growing from either end after being born. This was unexpected as related bacteria only start growing from the end opposite of where they pinched off their mother cell at division.

Together, the observations reveal that TB microbes use alternative strategies to increase variability among their offspring, challenging previous assumptions based on faster-growing and more uniform model organisms. Aldridge says the study will help her lab and other research teams better understand and exploit these mechanisms for treatment purposes.

"A lot of basic microbiology research is done in fast-growing model organisms, and while they're models for a reason, that doesn't make them representatives of other types of bacteria," said Aldridge. "There's an enormous diversity of life that we're not studying at the fundamental level and this work demonstrates why we need to study the pathogens themselves.”

Prathitha Kar of Harvard University, the other co-first author on the paper, and Maliwan Kamkaew, formerly of Tufts University School of Medicine, also contributed to the work.

Complete information on authors, funders, methodology, and conflicts of interest is available in the published paper. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

END

Study challenges assumptions about how tuberculosis bacteria grow

Researchers reveal how the deadly pathogen “breaks the rules” of bacterial biology

2024-11-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NASA Goddard Lidar team receives Center Innovation Award for Advancements

2024-11-15

NASA researchers Guan Yang, Jeff Chen, and their team received the 2024 Innovator of The Year Award at the agency’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, for their exemplary work on a lidar system enhanced with artificial intelligence and other technologies.

Like a laser-based version of sonar, lidar and its use in space exploration is not new. But the lidar system Yang and Chen’s team have developed — formally the Concurrent Artificially-intelligent Spectrometry and Adaptive Lidar System (CASALS) — can produce higher resolution data within a smaller space, significantly increasing efficiency compared to current models.

The ...

Can AI improve plant-based meats?

2024-11-15

Cutting back on animal protein in our diets can save on resources and greenhouse gas emissions. But convincing meat-loving consumers to switch up their menu is a challenge. Looking at this problem from a mechanical engineering angle, Stanford engineers are pioneering a new approach to food texture testing that could pave the way for faux filets that fool even committed carnivores.

In a new paper in Science of Food, the team demonstrated that a combination of mechanical testing and machine learning can describe food texture with striking similarity to human taste testers. Such a method could speed up the development of new and better plant-based meats. The team also found that ...

How microbes create the most toxic form of mercury

2024-11-15

Mercury is extraordinarily toxic, but it becomes especially dangerous when transformed into methylmercury – a form so harmful that just a few billionths of a gram can cause severe and lasting neurological damage to a developing fetus. Unfortunately, methylmercury often makes its way into our bodies through seafood – but once it’s in our food and the environment, there’s no easy way to get rid of it.

Now, leveraging high-energy X-rays at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) at the U.S. Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, ...

‘Walk this Way’: FSU researchers’ model explains how ants create trails to multiple food sources

2024-11-15

It’s a common sight — ants marching in an orderly line over and around obstacles from their nest to a food source, guided by scent trails left by scouts marking the find. But what happens when those scouts find a comestible motherlode?

A team of Florida State University researchers led by Assistant Professor of Mathematics Bhargav Karamched has discovered that in a foraging ant’s search for food, it will leave pheromone trails connecting its colony to multiple food sources when they’re available, ...

A new CNIC study describes a mechanism whereby cells respond to mechanical signals from their surroundings

2024-11-15

To the casual eye, a memory foam mattress would appear to have no relationship to the behavior of cells and tissues. But an innovative study carried out at the Centro de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC) in Madrid shows that viscoelasticity—the capacity of a material to be compressed and then recover its original form, like memory foam—is a little-explored property of biological tissues that is essential for correct cell function.

Study leader Dr. Jorge Alegre-Cebollada, who heads the Molecular Mechanics of the Cardiovascular System laboratory at the CNIC, explained that proper cell function requires ...

Study uncovers earliest evidence of humans using fire to shape the landscape of Tasmania

2024-11-15

Some of the first human beings to arrive in Tasmania, over 41,000 years ago, used fire to shape and manage the landscape, about 2,000 years earlier than previously thought.

A team of researchers from the UK and Australia analysed charcoal and pollen contained in ancient mud to determine how Aboriginal Tasmanians shaped their surroundings. This is the earliest record of humans using fire to shape the Tasmanian environment.

Early human migrations from Africa to the southern part of the globe were well underway during the early part of the last ice age – humans reached northern ...

Researchers uncover Achilles heel of antibiotic-resistant bacteria

2024-11-15

Recent estimates indicate that deadly antibiotic-resistant infections will rapidly escalate over the next quarter century. More than 1 million people died from drug-resistant infections each year from 1990 to 2021, a recent study reported, with new projections surging to nearly 2 million deaths each year by 2050.

In an effort to counteract this public health crisis, scientists are looking for new solutions inside the intricate mechanics of bacterial infection. A study led by researchers at the University of California San Diego has discovered a vulnerability within strains of bacteria that are antibiotic resistant.

Working with labs at Arizona State University and the Universitat ...

Scientists uncover earliest evidence of fire use to manage Tasmanian landscape

2024-11-15

Some of the first humans to arrive in Tasmania, over 41,000 years ago, used fire to shape and manage the landscape, a new study from The Australian National University (ANU) and the University of Cambridge has found.

It is thought to be the earliest and most detailed record of humans using fire in the Tasmanian environment.

According to the researchers, early inhabitants of Tasmania were managing forests and grasslands by burning them to create open spaces, possibly for food procurement and cultural activities.

The team analysed traces of charcoal and pollen contained in ancient mud that showed how Indigenous Tasmanians (Palawa) ...

Interpreting population mean treatment effects in the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire

2024-11-15

About The Study: Inferences about clinical impacts based on population-level mean treatment effects may be misleading, since even small between-group differences may reflect clinically important treatment benefits for individual patients. Results of this study suggest that clinical trials should explicitly describe the distributions of Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire change at the patient level within treatment groups to support the clinical interpretation of their results.

Corresponding ...

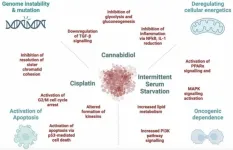

Targeting carbohydrate metabolism in colorectal cancer: Synergy of therapies

2024-11-15

“This commentary will discuss what is known about such combinatorial treatments, including potential mechanisms and future protocols.”

BUFFALO, NY- November 15, 2024 – A new review was published in Volume 11 of Oncoscience on November 12, 2024, entitled, “Targeting carbohydrate metabolism in colorectal cancer - synergy between DNA-damaging agents, cannabinoids, and intermittent serum starvation.”

As highlighted by the authors in the abstract of this review, chemotherapy is a common treatment for many cancers. However, it is often ineffective for long-term patient survival and ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

attexis RCT shows clinically relevant reduction in adult ADHD symptoms and is published in Psychological Medicine

Cellular changes linked to depression related fatigue

First degree female relatives’ suicidal intentions may influence women’s suicide risk

Specific gut bacteria species (R inulinivorans) linked to muscle strength

Wegovy may have highest ‘eye stroke’ and sight loss risk of semaglutide GLP-1 agonists

New African species confirms evolutionary origin of magic mushrooms

Mining the dark transcriptome: University of Toronto Engineering researchers create the first potential drug molecules from long noncoding RNA

IU researchers identify clotting protein as potential target in pancreatic cancer

Human moral agency irreplaceable in the era of artificial intelligence

Racial, political cues on social media shape TV audiences’ choices

New model offers ‘clear path’ to keeping clean water flowing in rural Africa

Ochsner MD Anderson to be first in the southern U.S. to offer precision cancer radiation treatment

Newly transferred jumping genes drive lethal mutations

Where wells run deep, biodiversity runs thin

Q&A: Gassing up bioengineered materials for wound healing

From genetics to AI: Integrated approaches to decoding human language in the brain

Leora Westbrook appointed executive director of NR2F1 Foundation

Massive-scale spatial multiplexing with 3D-printed photonic lanterns achieved by researchers

Younger stroke survivors face greater concentration, mental health challenges — especially those not employed

From chatbots to assembly lines: the impact of AI on workplace safety

Low testosterone levels may be associated with increased risk of prostate cancer progression during surveillance

Analysis of ancient parrot DNA reveals sophisticated, long-distance animal trade network that pre-dates the Inca Empire

How does snow gather on a roof?

Modeling how pollen flows through urban areas

Blood test predicts dementia in women as many as 25 years before symptoms begin

Female reproductive cancers and the sex gap in survival

GLP-1RA switching and treatment persistence in adults without diabetes

Gnaw-y by nature: Researchers discover neural circuit that rewards gnawing behavior in rodents

Research alert: How one receptor can help — or hurt — your blood vessels

Lamprey-inspired amphibious suction disc with hybrid adhesion mechanism

[Press-News.org] Study challenges assumptions about how tuberculosis bacteria growResearchers reveal how the deadly pathogen “breaks the rules” of bacterial biology